Bessie Margolin

Before there was the Notorious RBG, there was the Audacious Bessie Margolin. She rose from New Orleans’s Jewish orphanage to make her mark on the biggest issues of her day: she defended the constitutionality of FDR’s New Deal; she drafted rules for the Nazi War Crimes Trials at Nuremberg; and for more than three decades, she championed the Fair Labor Standards Act, ultimately including the Equal Pay Act, which led her to become a founder of NOW (the National Organization for Women). Margolin argued 24 times at the Supreme Court, one of only three women to do so in the twentieth century, and prevailed in cases associated with 21 of those arguments. While personifying excellence in law and public service, Bessie Margolin opened courtroom doors for countless women who have followed.

Childhood & Education

Bessie Margolin was born on February 24, 1909, to Russian Jewish immigrants Harry and Rebecca (Goldschmidt) Margolin in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York. To escape New York’s tough and crowded conditions, Bessie’s family made its way to Memphis, Tennessee. About a year after giving birth to a third child, Bessie’s mother died, leaving Bessie’s father alone to care for his three young children. Recognizing the Margolins’ plight, a Memphis rabbi petitioned New Orleans’s Jewish Orphans’ Home, which in 1913 admitted four-year-old Bessie and her siblings Dora and Jack as “half-orphans.” The children later reconnected with their father after leaving the Home as young adults, but the relationship remained strained until Harry’s death in 1940.

In the Home, Bessie grew up with more than 150 other needy Jewish children from throughout the South. In part due to the small size and the generosity of New Orleans’ Jewish community, the Home was unusual among institutions of its kind at the time. Although the assimilated German Jews of the community were not without condescension towards their Eastern European immigrant coreligionists, the Home was no Dickensian orphanage. Not content to provide its wards mere subsistence, the Home’s trustees groomed Bessie as an all-American girl who would reflect honorably on the local Jewish community and emulate the values and culture of her prosperous benefactors. Exposed to spiritual leaders who promoted progressive reforms to address root causes of poverty, Bessie’s childhood was informed by the pursuit of success and social justice.

In the Home, Bessie grew up with more than 150 other needy Jewish children from throughout the South. In part due to the small size and the generosity of New Orleans’ Jewish community, the Home was unusual among institutions of its kind at the time. Although the assimilated German Jews of the community were not without condescension towards their Eastern European immigrant coreligionists, the Home was no Dickensian orphanage. Not content to provide its wards mere subsistence, the Home’s trustees groomed Bessie as an all-American girl who would reflect honorably on the local Jewish community and emulate the values and culture of her prosperous benefactors. Exposed to spiritual leaders who promoted progressive reforms to address root causes of poverty, Bessie’s childhood was informed by the pursuit of success and social justice.

A gifted student, Margolin graduated from Newman School in 1925 as a sixteen-year-old leader who was comfortable competing and winning respect in a coed setting. Besides leading the debate club and girls’ student council, Margolin was valedictorian and won a scholarship to New Orleans’s Newcomb College, the women’s coordinate college of Tulane University. After two years at Newcomb, she ranked among the top ten in her class. But the audacious Bessie Margolin wanted more.

Margolin decided to attend law school—something no other girl from the Home had done. As Tulane law school’s only woman student at the time, Margolin felt isolated and self-conscious, but she and her male classmates soon adjusted to each other. In June 1930, at age 21, Margolin completed her liberal arts and law studies, with honors, in only five years. She graduated second in her law school class and was an editor of the Law Review.

In 1930, jobs were scarce—especially for a Jewish woman lawyer. But with glowing recommendations from Tulane Law School, Margolin secured a job as a research assistant at Yale Law School. In New Haven, she impressed the faculty, including William O. Douglas, future Supreme Court justice. With their help, Margolin became the first woman awarded Yale’s Sterling fellowship for graduate studies.

The New Deal Beckons

With her Yale doctorate in law, Margolin moved to Washington, D.C., equipped to compete against men for a new opportunity. She applied for a job at the Tennessee Valley Authority, which Congress had just created to realize President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal vision of supplying electricity to the Valley’s impoverished residents. A Yale law professor wrote what the TVA apparently needed to hear to hire a woman lawyer: that Margolin was intent on a legal career “as a primary objective from which she would not be deflected by consideration of marriage” (Letter from Ernest Lorenzen, Yale Law School, to Floyd Reeves, TVA). Margolin thus began her government career with a pledge that she would be married to her job instead of to a man, a pledge she honored for the rest of her career.

Fearing competition from the TVA, private utility companies hurled charges of socialism against the government, which quickly turned into lawsuits. Margolin proved herself integral to TVA’s brilliant legal team—and its only woman. She researched, prepared witnesses, and shaped the briefs for two landmark Supreme Court cases that upheld TVA’s power program, a New Deal cornerstone.

In March 1939, Margolin joined the Labor Department, where another New Deal program awaited enforcement. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 prohibited child labor and guaranteed minimum wages and overtime. Margolin was there as every aspect of the new law was challenged. She paid her dues reviewing time sheets in damp warehouses and traveling back roads to interview vegetable packers and log cutters. She began arguing (and winning) appeals in the circuit courts, and her high-quality work earned her the prestigious assignment of representing the Labor Department in cases headed for the Supreme Court. In March 1945, when future Supreme Court justices Sandra Day and Ruth Bader were still teens, Margolin—as only the 25th woman ever to argue at the Supreme Court—argued and won her first Supreme Court case. In this and the 24 Supreme Court arguments that followed, Margolin zealously sought to uphold the humanitarian purposes of the Act, to the full extent that Congress had mandated.

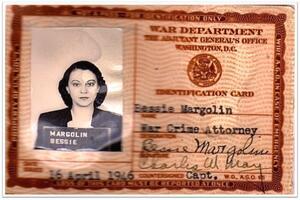

World War II Offers a New Legal Opportunity

In May 1946, Margolin was once again attracted by a new and exciting legal opportunity. On loan to the Army, she traveled to Nuremberg, Germany, to organize the American military tribunals. Once there, horrified to learn about what she called the Nazis’ “shocking and nauseating doctrines and crimes,” she concluded that “any little weight I may carry should be thrown in the direction of increasing the number of Nazis to be prosecuted for murder” (Letter from Margolin to John Lord O’Brian, June 2, 1946). For her six-month tour of duty, the Army’s commanding officer acknowledged Margolin’s primary role in drafting the rules that governed the war crimes trials of nearly 200 second-tier Nazis, including judges, doctors, and industrialists.

Return to the Labor Department

By the end of 1946, Margolin returned to the Labor Department, where see oversaw all of the agency’s trials and appeals. By the time she retired in 1972, she had directed the preparation of some 600 Supreme Court and appellate briefs, combined. Most impressively, Margolin personally argued 174 cases in the Supreme Court and circuit courts, winning an astounding eight out of every ten cases she argued, all to protect workers’ rights

Excerpt of Bessie Margolin’s humorous exchange with Justice Felix Frankfurter during the argument of Steiner v. Mitchell, March 1955. U.S. Supreme Court Recordings, Record Group 267, National Archives, College Park, MD.

Bessie Margolin was no great orator, often editing herself as she spoke. But she engaged the justices who respected her meticulous preparation and encyclopedic knowledge of the law. She also employed humor, something not often done with success at the Supreme Court. As a rare and striking woman at the high court, Margolin certainly drew attention, as evidenced by private notes Justice Felix Frankfurter wrote in 1959 to a male colleague. In one, Frankfurter referred to Margolin’s “deft use of her feminine charms” and in another to her “exploitation of her female talents.”

Pursuit of a Judgeship

In the early 1960s, Margolin decided to pursue a federal judgeship. She boldly set her sights on the U.S. Court of Claims or the D.C. federal appeals court, a particularly audacious goal given that there were then only two women federal judges in the entire country, and none on either court she wanted. With enthusiastic and influential supporters, Margolin’s name was considered by President Lyndon Johnson himself. White House tapes of Johnson’s discussions about Margolin recorded his impatient demand that an aide “just get that woman’s biography over here” (along with her photo) and his query, “What about this Jewish woman for the Court of Claims?” (Shreve and Johnson, 393, 557-58).

It remains unclear what if any role her earlier love affair with her married TVA boss (or the ensuing FBI and Congressional investigations) played in Johnson’s decision, but she faced other hurdles as well. One male White House staffer criticized Margolin’s fashion-forward appearance as “flamboyant” and another opined “that her age (58) would tend to preclude her from consideration” (John Macy Papers, LBJ Library). By 1968, Margolin had been passed over for seven federal judicial vacancies on those two courts alone, all filled by men, five older than she was.

The silver lining in Margolin not getting a judgeship is that she remained at the Labor Department, where she developed the strategies for and personally argued the first appeals under the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967. By the time she retired as Associate Solicitor of Labor, Margolin had overseen the filing of 300 Equal Pay lawsuits in 40 states, ultimately recovering millions of dollars for thousands of employees. Confronting the injustice working women faced, Margolin, the self-described “reluctant feminist,” had become a founding member of NOW (the National Organization for Women) and was dubbed by a reporter as the “nation’s number one fighter for equal pay for women” (Geiger).

As a case in point, the Equal Pay case of Shultz v. Wheaton Glass Company, perhaps Margolin’s most significant appellate victory, was likened in legal importance to “a second Brown v. Board of Education.” In that case, after Margolin presented two appellate arguments, the federal appeals court interpreted the Equal Pay law as it remains to this day: jobs need only be substantially equal—not identical—to require equal pay.

Retirement

In January 1972, having won every award the Labor Department offered and as one of the highest-ranking non-political women in federal government, Margolin retired. In her honor, the Secretary of Labor hosted a formal dinner the likes of which Washington has never seen since for a federal career employee. Margolin’s more than 200 guests included a dazzling constellation of justices, judges, and government dignitaries as well as colleagues and staff who were grateful for her prestigious and demanding tutelage. Chief Justice Earl Warren, retired, before whom Margolin had argued more than half of her Supreme Court cases, was guest speaker. On behalf of millions of Americans who did not know Bessie Margolin’s name, Warren thanked her for “developing the flesh and sinews” around the “bare bones” of the Fair Labor Standards Act, “because the bare bones of that Act would have been wholly inadequate without the implementation she forged in the courtrooms of our land.” Capturing her importance to women, Warren continued, “In this day and age when women are crying out for equality, [Margolin] has proved equality for them in a man’s world.”

Excerpt of Chief Justice Earl Warren’s remarks at Bessie Margolin’s retirement dinner, January 1972. Recording by U.S. Department of Labor.

In retirement, Margolin mediated federal labor disputes and taught labor law at George Washington University. Following complications from a stroke, she died on June 19, 1996, in Arlington, Virginia.

Bessie Margolin Papers, Manuscripts Collection 1094, Louisiana Research Collection, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Geiger, Joan. “Labor Department Solicitor Helps Women Get Equal Pay.” Seattle Daily Times, April 1, 1968.

John Macy Papers, Lyndon B. Johnson Library, Austin, Texas.

Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, Record Group 233, Select Committee to Investigate the Federal Communications Commission, box 9, folder “Bessie Margolin,” Subject Files, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Shreve, David and Robert David Johnson, eds. The Presidential Recordings: Lyndon B. Johnson. New York: Norton, 2007.

Trestman, Marlene. Fair Labor Lawyer: The Remarkable Life of New Deal Attorney and Supreme Court Advocate Bessie Margolin. Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press, hardcover 2016, paperback 2020.

Trestman, Marlene. “Fair Labor: The Remarkable Life and Legal Career of Bessie Margolin (1909-1996),” Journal of Supreme Court History 37, no. 1 (March 2012): 42-74.

Trestman, Marlene. “Addenda to ‘Fair labor: The remarkable life and legal career of Bessie Margolin’: A discussion of methodology in tallying Margolin's Supreme Court argument record as well as those of other pioneer female advocates,” Journal of Supreme Court History 38, no. 2 (July 2013): 252-260.

An audio recording of Margolin’s January 29, 1972 retirement dinner, including remarks by Chief Justice Earl Warren, retired, is available in the Laurence H. Silberman Papers, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University, Stanford, California.

Online Resources

- A list of all women who presented argument at the United States Supreme Court (October Terms 1880 - 2016), which identifies Margolin as the twenty-fifth, and accompanying essay, can be found on the Supreme Court Historical Society’s website at http://supremecourthistory.org/history_oral_advocates.html

- Photographs and audio clips of Margolin, as well as a timeline, are available on my website, www.marlenetrestman.com

- Book, Bella. “Breaking Glass Ceilings: Bessie Margolin and ‘The Woman Card,’” August 31, 2016, https://jwa.org/blog/breaking-glass-ceilings-bessie-margolin-and-woman-card