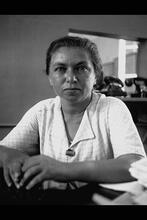

Sophie Irene Simon Loeb

At a time when widowed mothers often had no way to support their children, Sophie Irene Simon Loeb helped create support systems for needy children and their mothers. After losing her own father at age sixteen, Loeb worked to support her family. She later moved to New York City, where she began working as a journalist for the New York Evening World. Interviewing families that had been forced into even more dire situations than her own, Loeb became a persuasive advocate for widows and orphans. She served on the State Commission on Relief for Widowed Mothers, was president of New York City’s Child Welfare Board, and founded the Child Welfare Committee of America, pushing for better funding, legislation, and guidelines. Throughout, Loeb traveled to Palestine for her writing.

“Not charity, but a chance for every child.” Sophie Irene Simon Loeb adopted this as the creed of her life work for orphaned children in the United States and throughout the world. During the Progressive Era, Loeb was one of many women to enter the political arena through reform work, calling for government involvement to mitigate the problems of poverty. Loeb brought her life experience and her personalized approach to work for the rights of women and children to quality of life.

Migration to America and early writing career

Sophie Simon Loeb was born in Rovno, Russia, on July 4, 1876. In 1882, at age six, she and her parents, Samuel and Mary (Carey) Simon, and five younger siblings joined the great wave of Jewish immigration to the United States, settling in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh. Sophie’s father, a jeweler, died ten years later, leaving the family in dire straits. Still attending high school, she began part-time work in a local store to ease the family’s financial burden. She was teaching grade school when she married Ansel Loeb, an older man who owned the store where she had worked, on March 10, 1896. The marriage proved unsuccessful, and in 1910 the couple divorced and Sophie moved to New York City.

From Pennsylvania, Loeb had submitted essays to the New York Evening World on social discontent in the industrial town of McKeesport. Once in New York, she secured a position as a reporter and feature writer for the World. Loeb interviewed widowed women who, unlike her own mother, had been forced to place their children in orphanages. These interviews inspired her to work for the allocation of public funds for “widows’ pensions.” She publicized the movement to provide widows with such support, adding her voice to those of leaders—many of them Jewish women, children of immigrants—such as Hannah Bachman Einstein.

Child welfare advocacy

In 1913, Loeb and Einstein served on the newly created State Commission on Relief for Widowed Mothers. Loeb visited Europe for comparative studies of welfare policies. Her work on the commission report, as well as her campaign in the pages of the World, contributed greatly to the 1915 passage of a bill creating child welfare boards in every New York county. These boards distributed public funds to widowed mothers.

Loeb was appointed to New York City’s Child Welfare Board in 1915, and for eight years served as the board’s president. Under her direction, the board increased the city’s appropriation from $100,000 to $4.5 million. Loeb worked in many arenas of urban reform and used public schools for civic centers and community forums. Her call for an investigation into corruption within the Public Service Commission resulted in the appointment of a new body. In 1917, she served as the first woman strike mediator, settling a taxi industry strike in seven hours. During these same years, she worked with her friend Governor Alfred E. Smith on a commission to codify child welfare legislation in New York State.

Loeb extended her campaign for child welfare nationally and internationally. Her book Everyman’s Child (1920) addressed the themes of her campaign, stating that if any child fails to receive proper food and clothing, “the Government must stand in place of his parents.” She spoke before state legislatures throughout the country and in 1924 helped to found the Child Welfare Committee of America. She also served as its first president. In 1925, the First International Congress on Child Welfare in Geneva accepted her resolution endorsing family home life as opposed to orphanages. Her report on blind children in the United States was accepted by the League of Nations in 1926. Her travels, speeches, and articles contributed to the passage of widows’ aid legislation in forty-two states.

Loeb’s personal life and legacy

Though her mother had been an Orthodox Jew, Loeb maintained a secular life-style. In 1925, however, when the Evening World sent her to Palestine to report on Jewish settlements, Loeb was captivated by the Jewish homeland. She became a passionate Zionist, and her reports to the World were both investigative and romantic, full of arguments for welfare measures needed in the “pilgrimage center of all peoples.” The following year, she published Palestine Awake: The Rebirth of a Nation, a compilation of these articles, and donated all royalties to the Palestine Fund.

Even with her generosity to so many causes, and her refusal to receive a salary for her public service work, Loeb’s earnings from speaking and writing engagements—including authorship of several works of life observations, such as Epigrams of Eve (1913)—were high enough to afford her quite a comfortable life-style. Many mourned her loss when, on January 18, 1929, at age fifty-two, she died of cancer at New York City’s Memorial Hospital. Governor Alfred E. Smith praised her as “one of America’s most distinguished public servants, an indefatigable worker.” She is buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Westchester Hills, New York, where her gravestone reads: “Not charity, but a chance for every child.” Loeb’s work for scores of reform causes, particularly for new public policies of relief, served as the foundation for more expansive policies of welfare in the United States. She stands as one of the many important American Jewish women involved in social and political reform in the early part of the century.

Selected Works by Sophie Irene Simon Loeb

Epigrams of Eve (1913).

Everyman’s Child (1920).

Fables of Everyday Folks (1919).

Palestine Awake: The Rebirth of a Nation (1926).

AJYB 24:175, 31:93.

DAB; Liberty’s Women. Edited by Robert McHenry (1980).

NAW; Sickels, Eleanor. Twelve Daughters of Democracy: True Stories of American Women, 1865–1930 (1942).

“Sophie Irene Loeb.” NYTimes, January 21, 1929, 20:4.

“Sophie Irene Loeb, Social Worker, Dies.” NYTimes, January 19, 1929, 17:1.

UJE; WWIAJ (1926, 1928).

WWWIA 1.