Raquel Liberman

Raquel Liberman was born in Ukraine in 1900 and emigrated to Argentina as a young wife and mother in 1922. After the death of her husband she became a victim of human trafficking by the Zwi Migdal, a Jewish network that operated between Poland and Argentina luring innocent young girls into prostitution. In December 1930, Liberman denounced the Zwi Migdal to the police. In order to protect her two children she concealed the fact that she had been legally married in Poland and that she was a mother. Her information succeeded in bringing about the demise of the Jewish prostitution network in Argentina in 1935.

Family & Immigration to Argentina

Raquel (Ruchla Leah) Liberman was born in Berdichev in Ukraine on July 10, 1900. As a child, Raquel emigrated with her family to Warsaw. On December 21, 1919, she married Yaacov Ferber, a tailor, in accordance with Jewish rites. In 1920 the couple’s first son was born. A year later, while Raquel was pregnant with her second child, Yaacov emigrated to Argentina alone, to join his married sister and brother-in-law in the small village of Tapalqué, in the province of Buenos Aires. By the time Raquel and her sons Joshua David and Moshe Velvele (Mauricio) joined Yaacov in October 1922, he was already suffering from tuberculosis, and a few months later, he died.

Entering Prostitution

In order to support her family, and with no knowledge of Spanish, Raquel, aged twenty-three, found herself forced to leave her children behind under the care of a foster family, and look for a job in the capital, Buenos Aires. Unable to make ends meet from her work as a seamstress, she was either forced into or voluntarily entered prostitution. If facts and fiction about Raquel’s actual dealings are unreliable, it is partly because Raquel never wished the whole truth to be known.

Raquel was unlike other victims of exploitation, who were generally brought from Poland to Argentina by the Jewish human trafficking network Zwi Migdal with false promises of marriage and sexually exploited once in Argentina. When Raquel became a widow, she made a deal with the Zwi Migdal: she would practice prostitution in Buenos Aires and pay a percentage of her earnings to her pimp, Jaime Cissinger, in exchange for his protection and her freedom to travel periodically to Tapalqué, to visit her children, who would never find out about her trade.

Denouncing the Traffickers

With the money she managed to put away after four years, Raquel arranged to buy her complete independence from the Migdal. With the help of a compatriot, she opened an antique shop in Callao Street in Buenos Aires. Fearing that her example might encourage other victims, the organization began to harass, threaten, and steal her property. In October 1929, Raquel made her first denunciation to the police, in order to recover her money and stolen jewelry. She stated that even after she managed to pay for her freedom and become independent, she continued to suffer pressure from the traffickers. Simón Brutkievich, president of the Zwi Migdal, proposed to compensate her by returning her stolen goods on condition she cancel her denunciation, which she refused to do.

After her failure to recover her money from the Zwi Migdal, Liberman sought the help of Ezrat Nashim, the Society for the Protection of Girls and Women. This time the traffickers lured her into a marriage in order to force her back into prostitution on their behalf. Raquel married José Salomón Korn in a Jewish ceremony held at a synagogue at 3280 Cordoba Street. The marriage turned out to be fraudulent, and her new husband a notorious Zwi Migdal pimp who forced her to return to life in a brothel.

Raquel then issued her second accusation to the authorities on December 31, 1929. In this declaration to the police, she revealed only part of the truth about herself, deliberately choosing to keep her early life in obscurity. To protect her children, she stated that she had immigrated to Argentina in 1924 as a single woman, concealing her legal marriage in Poland and the birth of her two children. She also declared that she had been forced into prostitution and had been deceived by the traffickers.

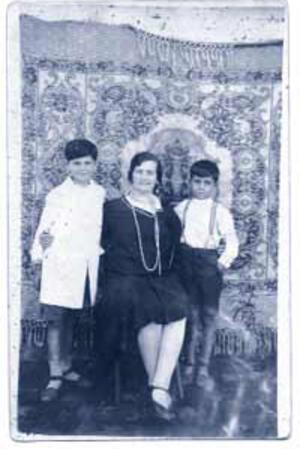

Raquel Liberman’s personal correspondence with her husband and relatives, written in Yiddish before her move to Argentina; an exchange of postcards with her children in Argentina; and dozens of family photos and legal documents in Polish were discovered in 1996. Raquel’s son had kept them in a shoebox, and Raquel’s grandchildren provided them to Rosalía Rosembuj and Nora Glickman, who translated them from Yiddish into Spanish and then English and published the archive in The Jewish White Slave Trade and the Untold Story of Raquel Liberman. These materials show beyond doubt that notwithstanding her report to the police in 1929, Raquel had come to Argentina as a married woman with children.

Dismantling the Zwi Migdal

Liberman’s denunciation against the Zwi Migdal proved to be successful for several reasons: It presented a unique opportunity to Chief Police Inspector Julio Alsogaray, who had been attempting for years to act against this organization for crimes of corruption, extortion and blackmail. The Jewish institutions in Buenos Aires openly confronted the “t’meyim,” the impure element, by mounting a campaign that consisted of expelling them from their community and preventing them from entering their synagogues and burying their dead in Jewish cemeteries.

In 1930, when the civil government of Hipólito Yrigoyen (1852–1933) fell as a result of the military coup d’état of General Uriburu, the time was ripe for a criminal court magistrate, Manuel Rodriguez Ocampo, to raid the headquarters of the Zwi Migdal, seize its documents, close dozens of brothels, deport numerous pimps and madams, and finally dismantle the organization with the arrest of many of its members. Nevertheless, out of the 434 active members who were brought to trial, only 108 were convicted, and most of them were freed soon after. The trial was effective, however, in leading to the dissolution of the Zwi Migdal in 1935.

The newspapers of the time displayed large front-page headlines and published detailed lists of the names of the traffickers and madams that operated the Zwi Migdal. As a result of Liberman’s courageous action, prostitution was banned in Argentina in 1935 and Raquel’s name became a symbol for the struggle of victimized women to obtain freedom from exploitation.

Legacy

Raquel Liberman died of thyroid cancer on April 7, 1935. She was 34 years old. Eighty years after her death, a plaque in her honor was placed at the cemetery of Avellaneda, where prostitutes and pimps were buried. In June 2010, the Raquel Liberman Award was created to honor those who promote and protect the rights of survivors of violence against women.

Multiple literary and historical works have been written about Raquel Liberman’s life. Nora Glickman’s The Jewish White Slave Trade and the Untold Story of Raquel Liberman is a historical account that examines her life in the context of the turbulent years she spent in Argentina and reproduces the entire collection of documents kept by Raquel’s family. Humberto Costantini’s posthumous Rapsodia de Raquel Liberman is a poetic eulogy. Many plays have explored her life (including Carlos Luis Serrano’s Raquel Liberman: Una historia de Pichincha, Nora Glickman’s bilingual play, Una tal Raquel /A Certain Raquel, and Patricia Suárez’s Las polacas), as have novels (Myrtha Shalom, La polaca, Ilán Scheinfeld, The Tale of a Ring). Myrtha Shalom’s Te llamarás Raquel and Leandro Calderone and Carolina Aguirre’s Argentina, tierra de amor y venganza are documentary television accounts, and Gabriela Bohm’s Raquel: A Marked Woman is a documentary film.

Video: Trailer for documentary “Raquel: A Marked Woman,” by Gabriela Böhm.

Alsogaray, Julio. Trilogía de la trata de blancas: Rufianes-Policía-Municipalidad. Buenos Aires: 1933.

Arlt, Roberto. “Que no quede en agua de borraja.” Diario Crítica, Mayo 23, 1930.

Bra, Gerardo. La organización negra: la increíble historia de la Zwi Migdal. Buenos Aires: Corregidor, 1982.

Bristow, Edward. Prostitution and Prejudice. New York: Schocken Books, 1982.

Deutsch, Sandra McGee, Crossing Borders, Claiming a Nation: A History of Argentine Jewish Women, 1880-1955. Duke University Press, Durhman, N.C. 2010.

Glickman, Nora. The Jewish White Slave Trade and the Untold Story of Raquel Liberman. New York: Garland Press, 2000.

Guy, Donna, Sex and Danger in Buenos Aires, University of Nebraska Press, 1991.

Yarfitz, Mir. Impure Migration: Jews and Sex Work in Golden Age Argentina. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2019.