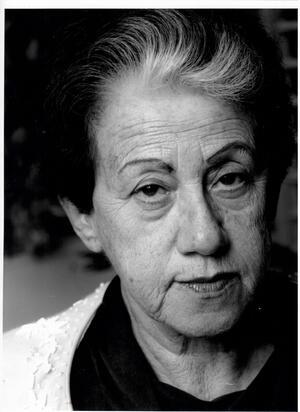

Erika Landau

Erika Landau was a psychotherapist and educator renowned for her interest in giftedness and creativity. She survived the Holocaust and attempted to immigrate illegally to what was then British Mandatory Palestine in 1947 with her mother and sister; they were caught by the British and transported to a Jewish displaced persons camp in Cyprus. Finally arriving in Israel in July 1948, she worked in a textile factory; when she was seventeen, she married the factory director, Shlomi Landau. The atrocities of the Holocaust shaped Landau’s worldview. She transformed survivors' guilt into a creative and active form. Her experiences helped her with her work with wounded Israeli soldiers and served as the basis for her educational and innovative work with the gifted around the world.

Early Life and Family

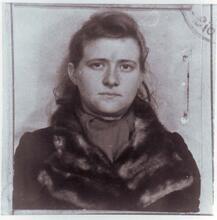

Erika Landau was born in Romania on October 15, 1931, to an affluent German-speaking Jewish family from Vienna. She was the youngest daughter of Rosa, a housewife who wrote poetry for pleasure, and Oscar Schechner, an importer of Jaffa oranges, and had one older sister Lily (Brill). Erika and Lily benefited from a rich home-schooling program, delivered by their mother and private tutors, which included foreign languages and the arts; Erika was regarded as a gifted piano player.

The Schechners' wealth enabled them to secure the family's safety during the first years of World War II, and young Erika was protected from antisemitism and Nazism. In 1940, the family feared that either the Nazis or the Soviets would occupy Romania. Consequently, they left their spacious home for a simple house in a nearby village, and Erika was forced to part with the piano she loved. In July 1941, however, nine-year-old Erika, her sister, and her parents were taken by the Nazis to a labor camp near the Dniester River, leaving her beloved family dog, Ceasar, forever. On the way to the labor camp, she was beaten, for the first time in her life, by a Nazi soldier—what she later referred to as her first life-changing experience.

The Schechner family stayed together in the same labor camp for the next four years of the war; Erika's father had to join the forced labor workers, while her mother took care of wounded workers and often had to hide her daughters. The family was liberated together from the labor camp, but six months later, when Erika was about fifteen years old, her father—who had survived the harsh forced labor—fell from a tram and became seriously disabled. Erika cared for him for eight months until his death.

Israel and Education

In 1947, Erika, her mother, and her sister attempted to immigrate to British Mandatory Palestine on an illegal immigration ship, but they were caught by the British on their way to Israel and sent to a displaced persons camp in Cyprus. They finally arrived via a legal immigration ship that brought displaced persons from Cyprus to the young state of Israel in July 1948.

Erika began work in a textile factory to help support her family. She soon fell in love with the director, Shlomi Landau; they married when she was only seventeen. The couple had no children, but Erika was close to her sister and nephews.

Shlomi, as Erika wrote, changed her worldview and made the child survivor into a Zionist Israeli. In her book The Importance of Meaning, she wrote, "You ask how one can love or help others after all that [the Holocaust]? This is a good question, and I struggled with it a lot. How does hate becomes love? […] Shlomi, my husband, taught me, with his wisdom, how to love again: to love him, myself, and my country. For me, Israel is not only a place to live or a home. It was the State of Israel that made me a human being again and gave me the right to civilize and evolve" (author’s translation, p. 38).

For many years, Shlomi encouraged his wife to pursue education, until she finally accepted his suggestion that she attend Tel Aviv University, where she studied for a BA in psychology and art history in the 1960s. She completed her BA cum laude. Professor Martin Buber advised her to continue her studies in psychology and art history at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, which she did in 1965. There she submitted her dissertation on "The Psychology of Creativity" and received a PhD in 1968. Her innovative study was published in several languages, including German, English, and Hebrew, almost immediately.

Theory of Creativity

In The Courage to Be Gifted, Landau presented creative thinking as an elastic capability that balances logic and imagination. While logical thinking governs categorization, interpersonal communication, and objective formulation, imaginative thinking suggests fluency in divergent ideas, intra-personal communication, and subjective reaction.

Landau’s theory of creativity's central claims are that a flexible, metaphorical approach and playfulness are necessary for generating ideas and thus for creativity. She argued that presenting these ideas depends on the ability to take risks and act as a leader (Vidergor: 138-139). Landau consistently emphasized the vital role of inner dialogue in the creative process and for achieving a state of equilibrium (Vidergor: 140).

A significant part of her work involved studying gender aspects, such as the personal, educational, and social barriers that prevent gifted girls with strong abilities in scientific thinking from pursuing science and mathematics (David: 31-33). Landau made minor adjustments to her theory over the years.

The Holocaust, Wars, and Peace

Landau’s memories from her creative childhood and her time in Nazi concentration camps shaped her theory of creativity, which was based on making order out of disorder and constructing an active and flexible self who looks for creative solutions.

Landau’s personal experiences helped her therapeutic work with wounded Israeli soldiers in the 1960s and the 1970s. She discussed the soldiers’ trauma in Father Had Died, a book that dealt openly with young persons’ and soldiers’ reactions to atrocities, severe injuries, and death in Israel after the Yom Kippur war.

After the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995, Landau attended the weekly memorial rally in his memory. Each Friday at noon, she and other peace activists wearing white stood next to the site of Rabin's assassination and advocated for the Oslo peace process.

Landau sought peace, and as she often mentioned in her interviews, she never let the atrocities of war consume her life force. In contrast to her public appearances, her weekly participation in the peace demonstrations at Rabin's murder site was known only to her family and friends. Her autobiographical drive, which she directed towards her book, The Importance of Meaning, is also evident in her creative dialogue with Viktor Frankl's Man's Search for Meaning. The Importance of Meaning opens with two questions: the first concerns a tear in Erika's right eye due to the intolerable memories, while the second concerns a tear in her left eye, "because I am alive" (p. 7), suggesting the paradoxical existence of a Holocaust survivor, a mixture of the burden of those who died and the happiness of surviving.

Young Person’s Institute for the Promotion of Creativity and Excellence

As a consequence of her harsh adolescence in a Nazi labor camp, Landau believed that, in most cases, gifted children should not be separated from their natural daily environment, and above all from their non-gifted siblings. Believing that the gifted needed not a special school but rather a special extracurricular enrichment center, in 1967 she established the nonprofit Young Person's Institute for the Promotion of Creativity and Excellence at the Eretz Israel Museum in Tel Aviv (MUZA). In the early 1980s, the institute was moved to the Tel Aviv University neighborhood. Today the Institute’s primary aim remains to provide gifted individuals with a space where they can create, belong, and be accepted as they are—helping them develop their intellectual, emotional, and social needs and abilities through workshops on various disciplinary and inter-disciplinary topics to prepare them to become creative, involved, and responsible adults who chose to live in Israel. The sense of belonging—to a family, a community, and a nation—was crucial to Landau’s personal and professional vision.

The Institute offers gifted individuals the opportunity to choose their learning subjects through a rich variety of programs that foster advanced questioning, curiosity, emotional maturity, leadership, and, above all, creative thinking; in other words, to be able to look at a given situation or a given problem from different angles. Landau described the educational work at the Institute in her popular scientific books The Courage to be Gifted and Emotional Maturity, published in Hebrew, English, and several other languages. Her academic work on creativity and giftedness was published continuously in distinguished, peer-reviewed science journals.

Along with her work at the Institute, Landau taught psychotherapy in the Department of Psychotherapy at Tel Aviv University's School of Medicine. She maintained a private psychotherapy clinic for adults and advised centers for gifted children around the world, including in Hungary and South Korea.

Later Life and Honors

Landau had many disagreements with the Israeli Ministry of Education and received hostile criticism (David: 145-163). Unlike the ministerial program, which called for offering special programs to gifted children, she advocated intellectual and social stimulation through interaction with other gifted children while keeping them in their natural environments. However, perhaps her central disagreement with the ministerial authorities was that she genuinely believed her way of running an after-school enrichment program was the only proper way to promote gifted children, and she never updated her interdisciplinary methodology to suit the new digital age and emerging technologies.

In 2008, Landau was selected to light a torch at the celebrations of the State of Israel’s 70th Independence Day. On April 3, 2008, the Independence Day ministerial committee wrote: "Dr. Erika Landau has been working for about forty years to educate generations of gifted and talented children who will form the next generation of young leaders in all areas of life" (Government Secretariat, Decision No. 3390). Local professional recognition of Landau’s contributions to Israeli society had finally arrived.

In the summer of 2012, approximately a year before Landau’s death, the Israeli Teacher Union (ITU) presented her with a lifetime achievement award in Tel Aviv. Subsequently, the International Center for Innovation in Education (ICIE) in Jerusalem presented her with the ICIE Award for Excellence in Gifted Education and wrote, "In appreciation and recognition of your dedication, commitment, leadership, and outstanding contributions to gifted education. You inspired professionals and institutions in this field of knowledge."

Erika Landau died on August 5, 2013.

Disclosure: During my childhood, I, Erga Heller, was a student at The Young Person's Institute for the Promotion of Creativity and Excellence, and later, from 1988 to 2008, I served on its educational, pedagogical, and publishing staff.

Selected Works by Erika Landau

Psychologie der Kreativität. München: Ernst Reinhardt, 1969. (German)

The Psychology of Creativity (הפסיכולוגיה של היצירתיות). Jerusalem: Israeli Ministry of Education, 1970. (Hebrew)

Creativity (יצירתיות). Tel Aviv: Gome Publishing House, 1973. (Hebrew)

Father Had Died (אבא מת). Tel Aviv: B. Tcherikover Publishing House, 1974. (Hebrew)

Kreatives Erleben. München: Ernst Reinhardt, 1984. (German)

The Courage to be Gifted. Unionville, NY: Trillium Press, 1990.

Mut zur Begabung. München: Ernst Reinhardt, 1990. (German)

"I am, Me, Myself" (a poem), manuscript, March 10, 1993.

Emotional Maturity (הבשלות הנפשית). Tel Aviv: Miskal, 1997. (Hebrew)

The Importance of Meaning (לתת משמעות). Tel Aviv: HaKibbutz HaMeuhad, 2000. (Hebrew)

El valor de ser superdotado. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, 2003. (Spanish)

David, Hanna. Erika Landau’s Contribution to the History of Gifted Education. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2025.

Government Secretariat [Government of Israel, the Prime Minister's Office]. Decision No. 3390 of the Ministerial Committee on Symbols and Ceremonies, March 19, 2008 (המלצת ועדת שרים לענייני סמלים וטקסים מיום 19.3.2008). Jerusalem: Government Secretariat. https://www.gov.il/he/pages/2008_des3390 (Hebrew)

Vidergor, Hava. “Erika Landau: A Lifetime of Creativity.” Gifted Education International 30, no. 2 (2014): 136–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261429413481123.

The Young Person's Institute for the Promotion of Creativity and Excellence. "Late Dr. Erika Landau's Life Story" (סיפור חייה של ד"ר אריקה לנדאו ז"ל), no date, https://ypipce.org.il/?page_id=27 (Hebrew)