Jewish Actresses in Bollywood

Persisting through the obstacles of negative stigmas surrounding acting, dangerous conditions while filming, language barriers upon the shift from silent films to talkies, and widespread prejudice towards Jewish people, Jewish women were fundamental in the development of early twentieth-century Indian cinema—as actresses, and later as producers. These women were some of the highest paid actresses of their time and were cast in a plethora of roles, ranging from femme fatale to the modern Indian woman. This success translated into entrepreneurial opportunities for some Jewish actresses, who went on to stage films through their own production houses. For instance, through her production house, Silver Productions, Pradmila became one of the principal producers of her day.

Jewish Women in Early Twentieth-Century Indian Cinema

Despite the fact that Jews are a micro-minority in India, Jewish women played a foundational role in the early twentieth-century Hindi film industry. The stories of Indian Jewish women, like those of other marginalized communities, have historically been ignored by official state archives and Indian society at large, and they have become even less recognized as India’s Jewish community itself has dwindled. At the community’s peak in 1940, approximately 22,480 Jews lived in British India; the twenty-first century population is only about 3,500. They were divided into sub-communities based on their geographic origins and lived in different parts of the country. The Jewish actresses primarily hailed from the “Baghdadi” Jewish community (based in Surat, Bombay, and eventually Calcutta), most likely because of their fair complexion and their relative freedom from Hindu and Muslim middle-class codes of respectability. [Notably, the term “Baghdadi” refers not only to Jews who came from Iraq but to all Jews who came from the Middle East, having migrated from countries such as Egypt, Syria, and Yemen (Nathan Katz 2020)]. Sulochana, Romila, Pramila, Rose, and Nadira are just a few of the Jewish actresses who left indelible marks on the industry.

In the formative years of Hindi cinema in the early twentieth century, the industry was primarily located in the west Indian city of Bombay (now known as Mumbai), specifically in the south-central neighborhood of Byculla. During this time, women from the majority Hindu and Muslim communities were (informally) prohibited from becoming professional performers, as it was considered dishonorable; women of respectable families were expected to remain at home, not in the workplace. Women from micro-minority communities, including Jewish, Parsi, and Anglo-Indian women, faced fewer restrictions when pursuing a career onstage, or indeed any career at all. Although they were often viewed disparagingly and aspersions were cast over their sexuality and morality, some women from these communities had successful careers as performers in India’s Hindi film industry (also known as Bollywood), while other worked as teachers, business owners, stenographers, and telephone operators.

Some of the earliest female Bollywood stars in the age of silent cinema were Jewish. Although these Jewish actresses were rarely acknowledged for the full scope of their contributions, their aesthetic and creative labors drew crowds to the cinemas. Unfortunately, because much of the cinematic material they produced has either been lost or remains only in fragments, efforts to understand these actors’ popularity and stardom has consisted largely of brief biographies or anecdotal information. The biggest challenge for scholars, however, has been the collapse of all micro-minorities into one amorphous whole, making it difficult to distinguish one community from another and sometimes leading to individual actors being miscategorized.

Jewish Actresses and their Screen Names

Within the Hindi cinema industry, actresses in general were quickly stereotyped as figures of both modernity and hyper-sexuality. Actresses, particularly those who were modern and western-educated, were cast as corrupt women with their own opinions and professions, in contrast to “cultured” women who upheld patriarchal respectability. In the early to mid-twentieth century, articles, discussions, and opinion pieces on women’s rights and the idea of the “modern woman” were common in English-language and vernacular newspapers and magazines. Discussions ranged from fashion to professions to ideas about what constituted the modern Indian woman. While Jewish women were rarely singled out in these conversations, actresses and the roles they played on screen and off screen were common topics of discussion.

Sulochana, born Ruby Myers (also spelled Mayers or Meyers) in 1907 to Jewish parents in Pune, Maharashtra, was one of the best-known actresses of the Silent era, her career later extending into the Talkies and Technicolor era. Sulochana was variously known as sitara (starlet), swapno ki rani (dream girl/queen), romance ki rani (romance queen), “Wildcat,” “India’s first sex symbol,” and India’s quintessential “Modern Girl.” Beginning her career with the Kohinoor Film Company, Sulochana eventually moved to the Imperial production house, where she became one of the highest-paid actresses. So successful was this partnership that Sulochana and Imperial became synonymous.

Several other actresses also had stage names given by producers or production houses. Iris Gasper, born in Bombay in 1914, came to be known as Sabita Devi. Esther Victoria Abraham, born in Calcutta in 1916, was given her stage name Pramila by the actor-productor Baburao Pendharkar. Her sister Sophie, who had a relatively short film career, acting mostly in stunt films like Chabukwali (Lady with Whip, 1938), Lady Robin Hood (1946), and Cyclewalli (Lady with Cycle, 1937), was known on screen as Romila. Another Jewish actress, Nadira, born Florence Ezekiel in Baghdad in 1932, was given her stage name by another actress named Sardar Akhtar.

The tradition of assigning screen names to actresses was, of course, not limited to those of the Jewish faith. Sardar Akhtar’s husband, producer-director Mehboob Akhtar, for example, named the actress Nargis, who was born Fatima Rashid in Calcutta in 1929, to a Muslim mother and a Hindu father who had converted to Islam. The fact that most stage names were Sanskrit or Urdu names led to chronic misidentifications and misattributions and obscured the heterogeneity of Indian cinema. As a result, Jewish actresses were often mistaken for Anglo-Indians or Muslims, or simply as “foreign.”

Jewish Actresses as Entrepreneurs

While there is no denying the power wielded by the production houses, many of the Jewish actresses were themselves successful entrepreneurs in the film industry. Both Sulochana and Pramila established their own production houses, called Rubi Pics and Silver Productions respectively. Indeed, with sixteen films under her banner, Pramila was one of the leading producers of the mid-twentieth century. Sabita Devi set up Sudama Pictures, a collaborative venture with director Sarvottam Badami and major production house Ranjit Studios. Films produced under the Sudama Pictures banner usually had famous script writers, were shot on elaborate sets, and were released with a great deal of hype and publicity (Patel 1937, 5). As an actress-entrepreneur, Sabita Devi successfully cultivated a coterie of like-minded partners, resulting in several hit films. She also invited women to use her platform as a safe launching pad into filmmaking. Asking "Why Shouldn't Respectable Ladies Join the Films" in a November 1931 issue of the English-language weekly Filmland, she challenged the ongoing debates around femininity and morality (Patel 1939, 5).

Roles for Jewish Actresses

Jewish actresses played a wide variety of roles on screen. Sulochana famously played eight different characters in the Wildcat of Bombay (1927), including a gardener, a policeman, a Hyderabadi gentleman, a European blonde, and an old banana-seller. Other actresses were depicted as glamorous, almost European vamps. Indeed, Nadira is often acknowledged as India’s quintessential femme fatale, particularly for her roles in Aan/The Savage Princess (Pride, 1952) and Shree 420 (1955). That said, Nadira’s prolific life and work, spanning over 60 films and crowned with a prestigious Filmfare Best Actress award (for Julie in 1973) cannot be flattened into one stereotype or sobriquet.

Jewish actresses also often played the role of the modern Indian woman, similar to the “Modern Girl” genre of “Social” films, in which vamps and prostitutes played lead roles and sought to a deliver a progressive social message. Films categorized as Socials explored “complexities of modernity facing middle-class households,” where “women were the protagonists” and were cast as urban professionals, such as telephone operators, typists, doctors, and teachers, “rebellious” figures who “questioned and transgressed gender boundaries” (Ramamurthy 2006). A good example of this kind of film is Dr. Madhurika (1925), in which Sabita Devi played the role of a “work-obsessed” doctor whose professional life inevitably begets a disturbed household. The “modern woman” worked as a cypher for staging conversations about gender, labor, home, modernity, and morality. Similarly, in a 1934 talkie, Indira M.A, Sulochana played the role of an Oxford-educated “modern woman” who rejects the suitor chosen by her father and instead marries a man of her choice, only for that marriage to end in divorce. Letters to editors of newspapers and magazines show that many viewers raised their voices against such portrayal of women, in which professional success automatically meant personal failure.

Jewish actresses also starred in several semi-autobiographical. For instance, Cinema Queen (1925), based on Sulochana’s life, offered an empathetic portrayal of the status and struggles of performers, while Telephone Girl (1926) reflected her life as a telephone operator before joining the film industry. The circulation of such stories of ordinary working girls who “made it” paralleled Hollywood films about class mobility and achieving the “American Dream” (Majumdar, 2009).

Indeed, by the late 1940s, impacted by world wars, the Depression, communism, and nationalism, the Socials acquired a new level of importance in Hindi cinema. The young bootstrapping Hindi cinema offered a range of valences within the genre of Socials. Some of the most prominent conversations around Indian modernity and the vision of an Independent India were manifested and embodied on screen through Jewish actresses.

Language Barriers in the “Talkies”

In the 1930s, the film industry saw a significant shift from silent films to talkies. This transition proved to be a challenge for some Jewish actresses who were not fluent in Hindi. Even a superstar of the stature of Sulochana, who at her peak earned more than the governor of Bombay, had to take a break from acting to improve her language skills. Upon her return to the industry, she quickly regained her status as the reigning star. While her films Sulochana (1933), Shair (Poet, 1949), and Baaz (Falcon, 1953) did brisk business, crabby film editors still criticized her for needing too many retakes. Curiously, the language issue played out differently for Pramila, whose Anglicized Hindi in fact became quite a rage. Pramila’s lesser-known cousin Rose Musleah, also known as Miss Rose, similarly managed to build a career that spanned the Silents and the Talkies. She starred in several movies, including Aparadhi (Criminal, 1931), Hum Tum Aur Woh (Us, you, and them, 1938), and Nayi Kahaani (New story, 1943). In the 1936 film Hamari Betiyan (Our Darling Daughters), she even co-starred with her cousin Pramila. Well into the 1950s, Miss Rose’s films drew large audiences.

While many of the Jewish actresses were able to successfully cross the language barrier and continue to work in the industry, the language issue nevertheless led to a deliberate “othering” of the performers. The non-Hindi speaking Jewish actresses were separated from the “cultured” and “respectable” Hindi-speaking Hindu and Muslim majorities. These complexities around language also shaped who made it into the archives, who got written out of history, and who is remembered.

Careers Before and After Bollywood

Many of the Jewish actresses of Bombay had successful careers before joining the film industry and beyond it. Sulochana, as mentioned earlier, was a telephone operator. Pramila taught kindergarten in the Talmud Torah Boy’s School and performed as a singer and dancer in JJ Madan’s Corinthian Theatre in Calcutta. In 1947, the year India became independent, she was crowned the first Miss India (a title that her daughter would also hold years later). Pramila’s sister Romila was also known for her skills in dance and theater, and she too was part of the Corinthian Theatre before joining the Women Auxiliary Force during second World War; soon after the war she died of cancer (Jewish Calcutta). Their cousin Miss Rose was also known for her talent in music and dance (Manasseh 2013, 308).

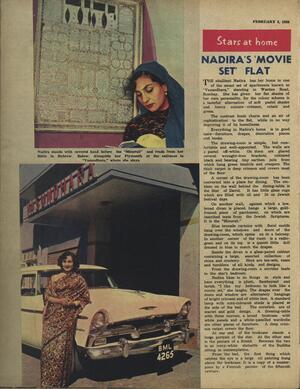

Nadira entered a career in films by happenstance, her choice to be a film actress shocking to those who knew her well. Indeed, she had initially intended to convert to Catholocism and become a nun (Varma 2005). Besides attending Catholic school, as a teenager she learned shorthand and typing at the Bombay Y.M.C.A, and she later aspired to be a doctor. However, her family faced financial challenges, prompting her mother to supplement funds by working in the Royal Air Force even after the end of the Second World War (Singh 1977). In need of money, Nadira accepted a job as an actress and began a long journey in Hindi cinema. Nadira lived in Bombay at her Vasundhara apartments and followed Jewish traditions. Capturing Nadira standing next to a menorah while reading from the Torah, a newspaper entry noted her aesthetically and carefully decorated Vasundhara apartment that gestured to her Jewish faith (Filmfare 1956). Because of the lack of archival sources, details about the everyday struggles, lived realities, dreams, and aspirations, as well as larger networks of kinship and alliances of Jewish actresses, have often disappeared. These small details in the newspaper article about Nadira’s home are valuable reminders of the quotidian nature of her faith that offer a necessary balance to the archetypal figures into which she and other Jewish women were slotted on screen.

Jewish actresses were also major influences in film industries outside of Bombay. Ramola (1917-1985), born Rachael Cohen, spent most of her childhood in Bombay but moved to Calcutta with her father Haym (Chaim) Cohen, a schoolteacher. Ramola’s active interest in amateur dramatics led her to acting on screen. Her first movie was a Bengali feature, Graher Fer (1937). “Discovered” by Kidar Sharma, Ramola came into the spotlight with Dalsukh Pancholi’s Khazanchi (Treasurer, 1941), based in Lahore (now in Pakistan) (Ramachandran 1989, 122). Known as the “rage of Lahore,” Ramola popularized the Punjabi Salwar Kameez, then known as the “Khazanchi dress” (Patriot 1988). She was a versatile artist and played a range of characters from vivacious to tragic; her popular movies include Masoom (Innocent, 1941), Kahmoshi (Silence, 1942), and Shukriya (Thanks, 1944). She also acted in the first Punjabi film Pardesi Dhola (Beloved foreigner, 1941), produced in Lahore. After India’s Partition, she moved to Bombay, continuing to make films in the Bengali and Hindi languages.

One of the few Hindi films about the Jewish community was the 1933 film titled Yahudi Ki Ladki (Daughter of a Jew), based on a play of the same name written by Urdu playwright Agha Hashar Kashmiri. Director Bimal Roy later remade the film under the title Yahudi (1958).

Lillian Ezra Jacob, a Baghdadi Jewish actress, caught Roy's attention when she appeared as an extra in the film. Born in Bombay to Orthodox Baghdadi Jewish parents Joe Sadick and Rachael Ezra, Lillian entered film as a teenager, encouraged by a friend, despite her parents' objections. She is perhaps best known for her role in Bimal Roy's 1957 film Apradhi Kaun? (Who is the culprit?). Lillian’s final film appearance was in the 1962 release Son of India, directed by Mehboob Khan (Manasseh 2017, 319).

Little is known about Vimala, Miss Solomon, or Aarti Devi, Jewish actresses from Calcutta and Bombay. Like Nadira and Ramola, many Jewish actresses took the Bombay-Hindi film industry by storm. After Partition, Jews and other micro-minorities, such as Anglo-Indians and Parsis, left India for other countries. Several Jewish families made Aliyah and moved to Israel, perhaps for greater safety and more opportunities. Today, the Jewish population of India has dwindled to a few hundred families. Despite the small size of the Jewish population, however, Jewish actresses exerted phenomenal influence on Indian cinema. They were central to shaping fashion, speech, femininity, and morality on the Indian screen; we live in their legacy despite their disappearance from public memory.

Working in the Bourgeoning Bombay Cinema Industry

Unlike the corporatized cinema industry in Hollywood, India’s film industry functions even today under the owner-run production house system; casting and production are improvised and chaotic. In the early to mid-twentieth century, this system meant that most actresses worked exclusively under the banner of a single production company, which then freely took all credit for their successes. These production companies controlled the careers of actresses through aggressive and punitive strategies, which made acts of refusal, protests, or dissent very uncommon. Therefore, it was not surprising that artists’ needs were often ignored, and the studio owner received credit for “discovering” and “nurturing” a star performer—even though such “discovery” was often by chance and based mostly on physical appearance and speculative audience appeal. When an actress was successful, she was derided for making too much money, while the (primarily male) members of the production house took all the credit for her fame.

While these issues were not limited to Jewish actresses, casual remarks about Jewish actresses and their earnings carried a willful derogatory note. For instance, the success of Baburao Patel, the well-known editor of the magazine Film India, often depended on riding the coattails of famous actresses. In a 1937 column titled “India Has No Stars,” Patel created a list of the top actresses of the time, based on their earnings. Sulochana topped the charts, with at least two other Jewish actresses, Rose and Sabita Devi, on the list as well. However, the reasons Patel gave for deeming these actresses unworthy of stardom were offensive. According to Patel, “Sabita Devi of Sagar Movietone,” third on the list, “is another Jew girl whom her producers have mentally placed on the supposed pedestal of stardom”; he considered her undeserving of stardom because “special stories are written for her” and she requires “plenty of rehearsals.” He also fostered acrimony towards these actresses by calling their earnings a “criminal waste of money” in “Mahatma Gandhi’s India where Indians cannot get two square meals a day.” In other words, Patel used a popular platform to decry these actresses as wasteful, unwelcome, uncultured women unworthy of their fame, whom “Our [male] producers have paid” to “chase star value.” He complained, “And yet none of the stars has obliged and paid her way back” (Patel 1937). Why does Patel rage against the successful actresses and specifically call out Jewish actresses? His comments perhaps resonated with some of India’s intellectual cinemagoers, who minimized the aesthetic labor of actresses as low-brow frivolous entertainment. Undoubtedly, cinema and popular culture played a crucial role in covert and subversive anti-colonial messaging, as much as it played into nationalist and patriotic storytelling in the years leading up to India’s Independence. Yet actresses, a common denominator in the parallel and intertwined existence of India’s freedom struggle and the modernizing landscape of Indian cinema, remain on the periphery of national political and Indian histories. Perhaps, this inability to “value” early actresses for their aesthetic labor in Indian cinema led to their easy removal from official archives.

White-passing Baghdadi Jewish actress were more agential than their Hindu or Muslim peers, due to their flexibility of aligning themselves as both Native and British. Yet their aesthetic labor as actresses in the burgeoning cinema industry put this privilege to the test. The harsh working conditions of actresses are documented by cinema historians, who conclude that the glaring lack of safety measures was visible through recurring on-set accidents, injuries, and occasionally even death. The agency of Baghdadi Jewish actresses did not shield them from such incidents. For example, cinema scholar, Debashree Mukherjee cites an accident in which Pramila nearly drowned while shooting a scene from the movie Jungle King in a water-absorbent costume. (Mukherjee 2020). Similarly, in a 1984 interview, Nadira shared a similar sequence of illegibility in the shooting of superhit movie Aan (1952), in which her screams for help were mistaken for a realistic take. As their safety became secondary to a successful take, these incidents question the degree of agency possessed by these working women in the early twentieth-century Bombay. Monolithic national histories remember these women as having benefitted from British colonialism and erase the real everyday bodily risks undertaken by them.

Indeed, some of the Jewish actresses’ struggles stemmed from the in-between place they occupied between “Native” and the “Anglo.” Jewish actresses were often not fluent in Hindi or Urdu, languages necessary for performing in Hindi cinema. That their lighter complexion, presumed agency, and imagined alignment with the British that ironically created their biggest challenges is often overlooked when imagining the lives of Baghdadi Jewish actresses. Members of a micro-minority illegible to both colonizer and colonized were easy to erase and forget during the rise of Indian nationalism in the early and mid-twentieth century.

Katz, Nathan. "Who Are the Jews of India?" [In English.]. (2000).

Majumdar, Neepa. Wanted Cultured Ladies Only! : Female Stardom and Cinema in India, 1930s-1950s. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

Manasseh, Rachel. Baghdadian Jews of Bombay Their Life and Achievements: A Personal and Historical Account. Great Neck, NY: Midrash Ben Ish Hai, 2013.

Ramamurthy, Priti. "The Modern Girl in India in the Interwar Years: Interracial Intimacies, International Competition, and Historical Eclipsing." Women's studies quarterly 34, no. 1/2 (2006): 197-226.

Roland, Joan G. Jews in British India : identity in a colonial era. Hanover, NH: Published for Brandeis University Press by University Press of New England, 1989.

Silliman, Jael. "05 Film Personalities and Others in the Public Gaze Pramila: Esther Victoria Abraham – a Star Studded Bollywood and Glamour Family in India." Recalling Jewish Calcutta: Memories of the Jewish Community in Calcutta. http://www.jewishcalcutta.in/exhibits/show/film_p/pramila_1

Magazine Articles, Courtesy of the National Film Archive of India, Pune

Kaul, Gautam. "Sulochana First of the Superstars." Filmfare, 08/23/1974, 1974.

Patel, Baburao (March 1939). "Editor's Mail". Filmindia. 5 (3): 15. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

Patel, Baburao (December 1937). "India Has No Stars". Filmindia. 3 (8): 5. Retrieved September 2, 2020

"Ramola Dead." Patriot, December 19, 1988.

"Stars at Home. Nadira’s ‘Movie Set’ Flat." Filmfare, February 3, 1956.

50 Years of Indian Talkies 1931-81. Edited by TM Ramachandran. Bombay: Indian Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, 122.

Singh, Patricia. “Nadira.” Filmfare 26, no. 19 (September 16, 1977).

Varma, Mini. "Nadira’s Neverland." Cine Blitz, 2005, 105-06.