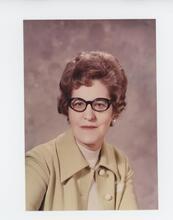

Tilly Edinger

Paleontologist Tilly Edinger, 1 November 1930

From Wikimedia Commons

Tilly Edinger pioneered the study of paleoneurology through her discovery that brains left detectable imprints on the insides of skulls. After earning her PhD in 1921, Edinger became the curator of fossil vertebrates at the Senckenberg Musuem in 1927. She continued to work at the Senckenberg Museum until 1938, when she finally fled Germany. In 1940 she took a research position at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, continuing her groundbreaking research and proving the importance of studying the brain’s evolution by examining fossil evidence, not just comparing modern species to each other. She served as president of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology from 1963–1964 and taught zoology for a year at Wellesley before retiring in 1964.

Tilly Edinger made her mark as one of the leading vertebrate paleontologists of the twentieth century. Her pioneering work in paleoneurology, the study of fossil brains, established her international reputation as the outstanding woman in her field.

Born on November 13, 1897, in Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany, Tilly Edinger was the youngest of three children of a wealthy Jewish family. Her father, Ludwig Edinger, was a well-known medical researcher and the founding director of the Frankfurt Neurological Institute. Her mother, Anna (Goldschmid) Edinger, was a prominent social activist and feminist. Her brother, Fritz, was killed during the Holocaust; her sister, Dr. Dora Lipschitz (Lindley), immigrated to the United States.

After studying at the Universities of Heidelberg and Munich, Tilly Edinger received her doctorate in natural philosophy from the University of Frankfurt in 1921, having written a dissertation on the skull and cranium of a fossil reptile. Her father objected to women pursuing a professional career, and her mother regarded fossil research as merely a hobby. Nevertheless, she continued working as an unpaid research assistant in the university’s institute for paleontology until 1927, when she became curator of fossil vertebrates at the Senckenberg Museum. She also served as a part-time assistant in the Frankfurt Neurological Institute after her father’s death, but she was happy to resign, rather than be fired, in 1933, since she greatly preferred studying the comparative brain anatomy of fossils to analyzing human brains.

After the Nazis came to power in 1933, Edinger encountered increasing difficulties because she was Jewish. She was able to continue curating for five more years, but her nameplate was removed from her office door, and she often had to use a side entrance. In 1938, the museum dismissed her, and she left for England in May 1939. While waiting for her American visa, she needed to earn money to support herself and translated German medical papers into English.

In recognition of her important scientific publications, the Museum of Comparative Zoology of Harvard University offered her a research position. She arrived in the United States in 1940 and became an American citizen in 1945. At Harvard, she continued her groundbreaking research on fossil brains, publishing a major book on the evolution of the horse brain and many controversial articles, as well as comprehensive bibliographies of her field. Her work proved the necessity of studying the brain’s evolution based on fossil evidence, rather than by comparing modern species. She received a Guggenheim Fellowship (1943–1944) and an American Association of University Women Fellowship (1950–1951). She was also president of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (1963–1964).

Edinger taught zoology for a year at Wellesley College, which also bestowed upon her an honorary degree, as did the University of Giessen (1957) and the University of Frankfurt (1964). But most of her career was devoted to research. She was described as feisty, strong-willed, and opinionated, but also warm-hearted. Due to a severe hearing impairment, she experienced increasing difficulty communicating with colleagues and students, and often engaged in extended monologues. However, even after her retirement in 1964, she continued her writing and worked in an advisory capacity.

Tilly Edinger always retained a sense of loyalty to her native town of Frankfurt-am-Main, but toward the end of her life she considered Boston her true home. She died on May 26, 1967, at age sixty-nine, a day after having been hit by a Harvard-owned truck in Cambridge.

Selected Works

Bibliography of Fossil Vertebrates, Exclusive of North America, 1509–1927, with A.S. Romer, N.E. Wright, and R.V. Frank. 2 vols. (1962).

The Evolution of the Horse Brain (1948); Die Fossilen Gehirne [Fossil brains] (1929).

Paleoneurology, 1804–1966: An Annotated Bibliography (1975).

SELECTED WORKS

Aldrich, Michele L. “Women of Geology.” In Women of Science, edited by G. Kass-Simon and Patricia Farnes (1990).

American Men of Science (1944): 501.

Backhaus-Lautenschläger, Christine. Und standen ihre Frau: Das Schicksal deutschsprachiger Emigrantinnen in den USA nach 1933 (1991).

Edinger, Tilly. Archives. Tilly Edinger Collection (AR-1267/4182 and 551/1479), Leo Baeck Institute, NYC, and Museum of Comparative Zoology Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

Hofer, H. “In Memoriam Tilly Edinger.” Gegenbaurs Morphologisches Jahrbuch 113, no. 2 (1969): 303–313.

International Biographical Dictionary of Central European Emigres. Vol. 2, part 1 (1980): 236.

Kaznelson, Siegmund, ed. Juden im Deutschen Kulturbereich (1959): 423.

Kohring, Rolf and Kreft, Gerald. Tilly Edinger: Leben und Werk einer jüdischen Wissenschaftlerin. Stuttgart, 2003.

Lexikon der Frau. Vol. 1: 872; NAW modern.

Obituary. NYTimes, May 29, 1967, 25:2.

Patterson, Bryan. Foreword to Paleoneurology, by Tilly Edigner (1975).

Romer, A.S. “Tilly Edinger, 1897–1967.” News Bulletin, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (October 1967): 51–53.

Rossiter, Margaret W. Women Scientists in America: Before Affirmative Action, 1940–1972 (1995).

Tobien, H. “Tilly Edinger.” Palaontologische Zeitschrift 42 (1968).