Jacqueline du Pre

Jacqueline du Pré was a world-renowned cellist whose career was sadly cut short due to multiple sclerosis. Born in Oxford, du Pré studied cello in Switzerland and quickly rose to international acclaim. Her famous recording of Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E minor with the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Sir John Barbirolli, was described as one of “the greatest recordings of the century.” Du Pré's repertoire was varied and impressive. Du Pré visited Israel in 1967, giving concerts before, during, and after the Six-Day War. In October 1973, she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, and she slowly lost her ability to play. Following her death, the Jacqueline du Pré Research Fund for Multiple Sclerosis was founded in the United States, Great Britain, Canada, and Austria.

Jacqueline Mary du Pré (“Jackie” to her family and friends) became known as an eminent cellist in August 1965, when she made her famous recording of Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E minor with the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Sir John Barbirolli. Later described as one of “the greatest recordings of the century,” this was a breakthrough in her career. Although her repertoire was varied and impressive, she won an unsurpassed reputation as a great cellist particularly in this concerto, which meant so much to her and which she performed countless times during the years, always fully committed.

Her account of the Elgar concerto gave it a powerful modern twist and her expressive interpretation was a revelation for many. (A second commercial recording of the Elgar concerto with du Pré as soloist was taken from a live performance in Philadelphia in November 1970, conducted by Daniel Barenboim, then already her husband.)

Early Life and Family

Du Pré was born in Oxford on January 26, 1945, the youngest daughter of Derek and Iris, in whose middle-class family music was part of daily life. She had a sister, Hilary, and a brother, Piers. Her father’s family came from the Channel Islands, the origin of the French name. Her mother was a fine pianist and a gifted teacher. The first time Jacqueline actually grasped a cello to play was when she was four years old, starting with lessons from her mother. At the age of six she began receiving lessons at the London Cello School. When she was ten years old she won first prize (the Suggia Gift Award) at an international competition, enabling her to further her studies under William Pleeth at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London. From the age of fourteen to fifteen she studied with world-famous cellists Pablo Casals in Switzerland, Paul Tortelier in Paris, and Mstislav Rostropovich in Russia—all of whom praised her talent.

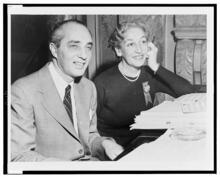

Her début as a cellist at the Wigmore Hall, London, on March 1, 1961, received highly favorable reviews. She soon became one of the most outstanding and beloved cellists in the world. Modest, sincere, and in full command of her instrument, she played in an expressive and emotional manner, as well as with precision and clarity of tone, from 1964 using a Stradivarius cello which an anonymous admirer had given her. At Christmas 1966 she met the Israeli pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim. Her love affair and professional cooperation with Barenboim and her friendship with musicians such as Itzhak Perlman, Pinchas Zukerman, and Zubin Mehta led to the film by Christopher Nupen of their performance of Schubert’s “Trout” Piano Quintet (1969).

Marriage and International Career

Du Pré and Daniel Barenboim visited Israel in summer 1967, giving concerts and recitals before, during, and after the Six- Day War. Their Jewish wedding ceremony, followed by an official celebration, took place in July 1967. Before the marriage, which aroused much public interest and enthusiasm in Israel, she converted to Judaism. All this seemed to her quite natural and easy and not at all problematic. As she said in a conversation with William Wordsworth, editor of the book Jacqueline du Pré: Impressions (London, 1983): “I think the thing that made it so easy for me is that the Jewish religion is perhaps the most abstract. Since I was a child I had always wanted to be Jewish, not in any definite way, because, of course, I didn’t understand anything about it. Possibly it may somehow have been to do with the fact that so many musicians are Jewish. …” In a BBC Television and Radio broadcast [on New Year’s Eve 1981] she said: “Daniel and I wanted our children brought up in the Jewish faith. But we have no children. I am sometimes asked if religion has helped me and I always reply: To be quite honest, not as much as music, because for me the Judaism is almost bound up in the music. I just cannot separate them or indicate their boundaries.”

In the middle of her successful international career the sound of du Pré’s cello suddenly started its irreversible decline. She began to lose sensitivity in her fingers and had to cancel performances and engagements. After a number of checkups, the final diagnosis, in October 1973, was multiple sclerosis. This was a real tragedy. Later on, during years of struggling against the illness, she gave master classes, lessons, and courses while sitting in a wheelchair. But she was no longer able to play. Barenboim assisted her in a wonderful way, despite his many obligations and performances. Before her cello became silent, she, fortunately, managed to record some of the best works for cello—both concertos and sonatas, which are still available.

Later Life and Legacy

Blessed with a genuine gift of optimism and hope, du Pré often described herself as a lucky person, despite her tragic situation. On October 19, 1987, at the age of forty-two, she died at her home in London and was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Golders Green. Many famous musicians and old friends attended the funeral. Barenboim recited the Lit. (Aramaic) "holy." Doxology, mostly in Aramaic, recited at the close of sections of the prayer service. The mourner's Kaddish is recited at prescribed times by one who has lost an immediate family member. The prayer traditionally requires the presence of ten adult males.Kaddish and Rabbi Albert Friedlander read Psalm 23 in Hebrew.

A Jacqueline du Pré Research Fund for Multiple Sclerosis was founded in the United States, Great Britain, Canada, and Austria. Remembered as one of the greatest and most humane cellists ever, du Pré was awarded numerous honors, including the Order of the British Empire (1976) and honorary degrees from the universities of London, Leeds, Durham, Oxford, and others.

In 2004, Barenboim donated one of du Pré’s valuable instruments to a talented young Israeli cellist, Amichai Grosz, a member of the Jerusalem Quartet.

Video/DVD

Remembering Jacqueline du Pré. A film written and directed by Christopher Nupen. London: 1994

Books

Wordsworth, William, ed. Jacqueline du Pré: Impressions (various articles by relatives, colleagues and friends). London: 1983.

Wilson, Elisabeth. Jacqueline du Pré: Her Life, Her Music, Her Legend. New York: 1999.

SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY

Beethoven. Complete Cello Sonatas 1–5; Variations for cello and piano; Trios Op. 70 1–2. With Daniel Barenboim and Pinchas Zukerman. EMI.

Boccherini. Cello Concerto in B-flat. ECO. Daniel Barenboim, conductor. EMI.

Brahms. Cello Sonatas 1–2. With Daniel Barenboim. EMI.

Britten. Cello Sonata in C. With Gerald Moore, piano. EMI.

Bruch. Kol Nidre. With Gerald Moore, piano. EMI.

Dvorak. Cello Concerto in b minor. Silent Woods, Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Daniel Barenboim, conductor. EMI.

Elgar. Cello Concerto in e minor. London Symphony Orchestra, Sir John Barbirolli, conductor. EMI.

Fauré. Elegie in c minor. With Gerald Moore, piano. EMI.

Haydn. Cello Concerto in C major. ECO. Daniel Barenboim, conductor. EMI.

Lalo. Cello Concerto in d minor. Cleveland Orchestra, Daniel Barenboim, conductor. EMI.

Saint-Saens. Cello Concerto No. 1 in a minor. NPO, Daniel Barenboim, conductor. EMI.

Schumann. Cello Concerto in a minor. NPO, Daniel Barenboim, conductor. EMI.