Drisha Institute for Jewish Education

Drisha Institute for Jewish Education was founded in 1979 to provide women with the then-unprecedented opportunity to engage in traditional, in-depth study of classical Jewish texts. Headquartered in Manhattan, as of 2021 Drisha offered programs in New York, Israel, and online, for high school girls and adults of all ages and genders. Drisha is officially nondenominational and welcomes students from all backgrounds. At the same time, it has functioned over the decades as a cornerstone of the Orthodox feminist movement, and most of its faculty are traditionally observant. In the twenth-first century, it has been one of a number of New York institutions, some non-denominational, some Orthodox, that promote intense engagement with Talmud and traditional halakha with a liberal cultural orientation.

Origins and Development

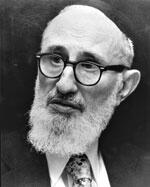

Drisha Institute for Jewish Education began as an institute for women and has since expanded to serve students of all genders. When it opened in New York in 1979, it was one of a handful of initiatives aimed at providing Orthodox women with opportunities for extended Torah learning, including the study of Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud. Its founder and dean, Rabbi David Silber, was a recent graduate of Yeshiva University’s rabbinical school who wanted to equalize access to core texts, allowing women to contribute their talents to the Jewish community by teaching and in other new leadership roles.

Drisha began with part-time classes, but the offerings quickly expanded to fulfill Silber’s vision of full-time learning in the style of a kollel, a traditional study hall for adults. In 1984, eight students began a full-time Houses of study (of Torah)Beit Midrash program, earning stipends. In 1988, a summer program for high school girls was added, and a full-time, three-year certificate program called the Scholar’s Circle began in 1994. Meanwhile, part-time community education courses remained central. Over the years, the community education classes became co-educational. Drisha has also run short-term intensives and various professional development programs open to people of all genders. The organization also maintains a freely accessible online library of lectures.

Drisha’s full-time fellowships for women in New York closed in 2014, largely because the growth in other advanced learning opportunities for Jewish women had reduced demand, while the shorter term, co-educational programming and the girls’ high school program remained strong. Four years later, in 2018, Drisha opened a new center in Gush Etzion, Israel, for intensive study for women, called Yeshivat Drisha. Initially focused on advanced, multi-year study, in 2020 the yeshiva added a single-year “Shana Alef” program for young women from Israel and around the world.

Women Studying Talmud

Torah study, meaning the study of the biblical and rabbinic canons, is a core devotional practice in Judaism. Textual expertise, particularly in Talmud, confers status and authority on anyone possessing it and is a prerequisite for rabbis interpreting Jewish law. Before the twentieth century, however, Torah study was almost exclusively reserved for men. This changed gradually, and the 1970s saw the beginning of what has been described as a “revolution” in traditional learning of Talmud by Orthodox women. Drisha was an early and influential part of this movement, which has accelerated through the first quarter of the twenty-first century. The expansion of textual education has created a cohort of female experts with unprecedented potential to challenge the male monopoly on religious leadership in Orthodox Judaism.

In the premodern period, rabbis worldwide had generally disapproved of training girls and women in any Jewish texts. In the early twentieth century, the Bais Ya’akov schools established the legitimacy of formal education for girls in Bible and other Jewish topics. However, most Orthodox rabbis considered the study of Talmud and The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah to remain off-limits for females, and non-Orthodox seminaries did not typically train women. Some Modern Orthodox rabbis, however, including the luminary Joseph B. Soloveitchik, approved of teaching girls Talmud, and a few American high schools began doing so in the 1940s. However, it remained rare for women to achieve the learning necessary to study Talmud independently, and there were no opportunities for advanced study for adult women.

The women’s liberation movement and a general intensification of textual education for American Modern Orthodox youth combined in the 1970s to produce an expansion of Talmud study for females. When Drisha opened, this expansion had just begun and was still limited to girls and young women. A few Modern Orthodox high schools had been teaching female students Talmud since the 1940s, and Stern College, the women’s college of Yeshiva University, opened a part-time Beit Midrash program for its undergraduates in 1977. These programs had the blessing of Joseph B. Soloveitchik and Yeshiva University, which lent them legitimacy in the eyes of the American Modern Orthodox mainstream. In Israel, Michlelet Bruria also opened in 1977, initially teaching mostly American students. Though Drisha was at the vanguard, it was not alone, and founder David Silber later recalled that “I didn’t realize at the time that I was doing something revolutionary” by starting Drisha.

Over the subsequent decades, more and more Modern Orthodox women around the world began learning Jewish texts, and women’s programs of many types proliferated. For a long time, Drisha was nearly unique for the intensity and advanced level of the study offered at its full-time programs, such as the three-year Scholar’s Circle. Drisha remained the only institution in North America offering full-time text study to Orthodox women until the opening of Yeshiva University’s Graduate Program in Advanced Talmud Study in 2000. Since then, it has also been joined by Yeshivat Maharat [link to new entry on Yeshivat Maharat], an Orthodox rabbinical school for women in New York. In Israel, other advanced programs are available, such as Nishmat (founded 1990), which trains women as halakhic advisors.

The growth in opportunities for Jewish learning for women seems to have reduced demand for Drisha’s intensive programs. In the twenty-first century, Orthodox women interested in devoting their lives to Jewish study, teaching, and halakhic interpretation are increasingly likely to aim for Rabbinic ordinationsemikhah, which Drisha does not offer. Drisha’s Scholar’s Circle program saw declining enrollments in the 2000s, and all its single-sex advanced programs in New York closed in 2014, though the new women’s yeshiva opened in Israel a few years later. The high school program remains girls-only, and its participants now have an array of options for future study

Orthodox Women Rabbis

In the early twenty-first century, some activists began working to allow women to become Orthodox rabbis. Because learnedness is the major rabbinic qualification, this effort depended on the expansion of women’s text study. Though Drisha has never granted semikhah, it provided an important basis for the movement to ordain women, particularly through the training provided by the Scholar’s Circle fellowship.

The Scholar’s Circle curriculum paralleled a traditional rabbinical training program and conferred a certificate on students who completed the three-year program. Numerous alumnae have had careers teaching and studying Jewish texts, in positions usually filled by rabbis. An illustrious example is Scholar’s Circle alumna Devorah Zlochower, who became Rosh Beit Midrash (dean) at Drisha in 2005 before taking the role of Rosh Yeshiva at Yeshivat Maharat.

Many Drisha fellows have also broken ground as the first women in clergy roles in Orthodox congregations. For example, of the two women that made headlines in 1998 when prominent Modern Orthodox synagogues hired them as “congregational interns,” one, Julie Stern Joseph, was studying at Drisha at the time. Dina Najman, the first woman to officially lead a traditional congregation, is also a Drisha alumna. Najman, like other scholars serving in rabbinic roles, uses her textual expertise gained from study at Drisha and other seminaries to make halakhic decisions for her congregation. A number of Scholar’s Circle alumnae have been ordained by Orthodox rabbis since completing their time at Drisha. These include Najman and Sara Hurwitz [link to new entry on Sara Hurwitz], who is sometimes considered the first female Orthodox rabbi in the United States (ordained in 2009) and who co-founded Yeshivat Maharat.

The Liberal Observant Pluralist Ethos

While most of Drisha’s faculty and its core constituency have been Modern Orthodox, Drisha contributes to a renaissance of liberal observant religious culture that transcends denominational boundaries. Drisha itself is officially non-denominational and takes pride in its pluralism. Drisha also embraces mixed-gender study and promotes an “open-minded” pedagogy that combines serious treatment of texts with intellectual honesty and consideration of ethical issues, typical characteristics of the liberal observant religious approach.

Drisha’s pluralism sets it apart from most women’s Torah study institutions. Drisha has been renowned for its learning environment where people from all walks of life come together to access Jewish texts directly, respecting differences and appreciating the range of insights. Reni Dickman, who spent time at Drisha in the 1990s while studying to be a Reform rabbi, told the Jewish Women’s Archive at that time that she never felt uncomfortable as a Reform Jew in what many would consider a traditional or even Orthodox setting. In the twenty-first century, Drisha’s adult programs in New York City continue to attract students with a range of commitments, including rabbinical students at the liberal seminaries. The organization estimated in 2021 that up to half of participants in its intensive programs have non-Orthodox backgrounds, while the high school program and Yeshivat Drisha draw predominantly Orthodox participants.

Communal prayer at Drisha reflects the institute’s pluralist stance, as well as its tendency towards traditional styles. When Drisha students pray together at the full-time programs, their own preferences determine the prayer style. The students usually choose some combination of traditional The quorum, traditionally of ten adult males over the age of thirteen, required for public synagogue service and several other religious ceremonies.minyanim, Orthodox women’s prayer groups, and gender egalitarian minyanim with traditional liturgy. Often, multiple options exist.

Drisha is not alone in its approach but is part of a network of organizations devoted to promoting traditional Jewish religious life in tandem with progressive values like gender equality, tolerance, and social justice. Over the years, Drisha has been closely connected with other feminist Orthodox institutions. Drisha scholars have consistently featured at the conferences of the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance [link to new entry on JOFA] (founded 1998), and, as noted above, they figure prominently among women who have become Orthodox rabbis. In the last two decades, cross-denominational ties have also appeared. For example, the Community Beit Midrash in Manhattan (2018-2019) was co-hosted by Drisha, Hadar (non-denominational and egalitarian), the Jewish Theological Seminary (Conservative), Yeshivat Maharat (Modern Orthodox), and the Shalom Hartman Institute and Pardes (both pluralist with a Modern Orthodox bent). These and other similar organizations (not to mention their individual participants) do not agree in all particulars, but they engage in a shared conversation. For example, these organizations do not all endorse the same ways of including women in communal prayer while still respecting halakhah, but all are invested in both equality and halakhah as guiding principles.

Conclusion

In the four decades since it opened, Drisha has served thousands of part-time and full-time students, both men and women. It has contributed to the Orthodox feminist movement by promoting a vision of gender equality and women’s religious leadership, by bringing like-minded people together, and above all, by providing a space for women to acquire textual expertise. While still inspired by feminist ideals, Drisha’s New York center now focuses on mixed-gender learning opportunities. These programs, as well as the yeshiva in Israel, are structurally similar to other Jewish education organizations. If Drisha’s programming is no longer unique, it is in part because it pioneered a vision of inclusive Torah study that others eagerly took up.

“Drisha: Into the Future.” Advertising Supplement to The New York Jewish Week, January 13, 2006.

Drisha Institute for Jewish Education Website, 2021. https://drisha.org/.

Eden, Jennifer Lerer. “Knowledge, Power and Women: New York’s Drisha Institute Attracts Female Jews of All Backgrounds.” Jewish Exponent, August 19, 1999.

Eleff, Zev. Authentically Orthodox: A Tradition-Bound Faith in American Life. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2020.

El-Or, Tamar. Next Year I Will Know More: Literacy and Identity among Young Orthodox Women in Israel. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2002.

Greenberg, Blu. 1993. “Is Now the Time for Orthodox Women Rabbis?” Moment 18: 50–53.

Hanau, Shira. “Drisha Leaving West Side Home For NYU; Expanding To Israel.” The New York Jewish Week, Manhattan Edition, December 22, 2017. https://jewishweek.timesofisrael.com/drisha-leaving-west-side-home-will-open-yeshiva-in-israel/.

Jewish Women’s Archive. “Drisha Institute Graduates Its First Female Talmud Scholars.” Accessed January 27, 2021. https://jwa.org/thisweek/aug/18/1996/dije.

Liebler, Soshea. “Drisha Institute for Jewish Education.” In Modern Orthodox Judaism: A Documentary History, edited by Zev Eleff, 206–7. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 2016.

Mark, Jonathan. “Reassessing An Experiment.” The Jewish Week, May 26, 2000. http://jewishweek.timesofisrael.com/reassessing-an-experiment/.

Silber, David. “It’s Your Torah.” The JOFA Journal, Fall 2019, 6-7.