Ruth Dar

Renowned Israeli designer Ruth Dar’s entry into the theatrical world began as a member of the Israel army’s Nahal Entertainment Troupe. After completing her military service, Dar took evening classes at Avni Art Institute and studied at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design. She studied set design and costumes at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre and opera house in London. Upon her return to Israel, Dar began working as a set and costume designer, becoming the most prominent and respected designer in mainstream Israeli theater. Dar works consistently with the top directors in Israeli theater. Her talents as a set and costume designer are demonstrated in her fruitful and creative dialogue with her theatrical partners and the visual transposition of the director’s conceptual emphases.

“A stage set is like a painting that comes to life, becoming three-dimensional. Like a moving sculpture!” (Ruth Dar in Hotem, December 29, 1978). “I call this profession ‘painter’ and not set designer. I paint with space and costumes, and in my eyes there is no real difference between the two because the costumes are part of the concept of the space … Since I’m a minimalist, there is nothing extraneous on stage. Every little object that is there has a reason, and it has to have a place in the whole. I prefer to telegraph a spatial concept. For this reason, I have never done a set of a room with four walls and a few chairs” (Ha-Ir, June 12, 1997).

Early Life and Family

Ruth Dar is a native of Tel Aviv. Her father, Yosef Polan (1900–1970), was born in Warsaw, Poland and came to Palestine in 1926. A farmer-pioneer, he joined the fledgling A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.Kibbutz Mishmar Ha-Emek. He later became a member of the Ohel theater troupe, and after a brief stint as a performer, traveled to Cannes, France to study engineering. Upon his return to Palestine, he worked as an engineer with the Solel Boneh construction company. It was on Mishmar Ha-Emek that he met Hannah Smolnik, his future wife and the mother of Ruth and her sister Amira. In 1964, Ruth married stage actor and director Ilan Dar (b. 1937). Their daughter, Arel, was born in 1979. The Dar family lives in Tel Aviv.

Theater Debut and Career

Ruth Dar’s entry into the theatrical world began as a member of the Israel army’s Nahal Entertainment Troupe (1961–1962). After completing her military service, she performed for some three and a half years at Haifa Theater and Mo’adon Ha-Teatron. During this period, she took evening classes at Avni Art Institute and studied for a year at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design (1963). With the encouragement of British director Julius Gellner, Ruth and Ilan Dar traveled to London. From 1967 to 1969, Ruth studied set design and costumes at the school of the Sadler’s Wells Theatre and opera house in London. Upon the couple’s return to Israel, Ruth began working as a set and costume designer, becoming one of the most prominent and respected designers in mainstream Israeli theater, as attested to by the many awards she has received over the years: Avraham Ben-Yosef Award (1980), Meir Margalit Award (1982), the Moshe Sternfeld Lifetime Achievement Award (2001) and the Gottlieb and Chana Rosenblum Award (2004). She was a winner of the Israeli Theater Prize for set and costume design for Bikur ha-Geveret ha-Zekenah (The Visit of the Old Lady, 1995) and Ha-Mordim (The Rebels, 1998); for set design for As You Like It (2001); and for costume design for Ha-Te’omim mi-Veneziyah (The Venetian Twins, 1997); Ootz Li Gootz Li (Rumpelstiltskin, 2003); and Kaviar ve-Adashim (Caviar and Lentils, 2004).

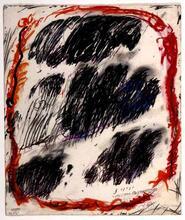

Dar has faced many challenges throughout her professional career, among them plays from assorted periods and genres, and varied approaches to directing. Dar works consistently with the top directors in Israeli theater, including Omri Nitzan, Ilan Ronen, Michael Gurevitz, and the late Hanoch Levin. Her talents as a set designer and costume designer are demonstrated in her fruitful and creative dialogue with her theatrical partners and in the visual transposition of the director’s conceptual emphases. Thus, for example, in Richard III, directed by Omri Nitzan (1992), tall transparent pillars stuffed with inflated black plastic bags were lit from different angles by two sets of spotlights. The first caused them to look like pillars of black marble, while the other was lit up only when Richard ascended to power, exposing the black plastic bags within. This illustrated the concept of stepping on bodies on the way to the “top.”

Design Work

In the transition from city to forest in As You Like It, under the direction of Omri Nitzan (2001), the space metamorphosed from the concrete to the illusory, from hard to soft, from metallic to woolen, from gray to white—a transformation whose material expression was endless amounts of a white woolly substance that filled the stage and served as a substitute for the traditional image of the forest, conveying the feel of the woods in a sensual-experiential manner.

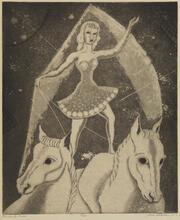

The scenery for the musical Shlomo Ha-Melekh ve-Shlomi ha-Sandlar (King Solomon and Shlomi the Cobbler), which holds a special place in the historiography of Israeli theater as the country’s first musical (Cameri Theater, 1964), consisted of two basic two-dimensional sets, identical in structure, of a marketplace and a palace. The costumes displayed an abundance of taste and imagination: warm pastels in the marketplace, and blue and gold splendor in the palace brought the production, under the direction of Ilan Ronen (Habimah, 2004), to a new level.

Dar’s rich collection of images is fed by various sources of inspiration that serve as a firm foundation for a unique, original visual world filled with imagination. Thus, the inspiration for the set of Michael Kohlhaas, directed by Ilan Ronen (1986), came from the woodcuts of Jacob Pins that illustrate the books Michael Kohlhaas and Till Eulenspiegel; the drawings of Brueghel; and the principles of shadow theater, which combined to produce a distilled image of the Middle Ages.

In The Venetian Twins, under the direction of Michael Gurevitz, the works of René Magritte served as a visual key to the portrait of a surrealistic magical city. Dar has also designed sets for the New Israel Opera, including such productions as L’Elisir d’Amore (1997) by Donizetti, and Masa el Tom ha-Elef (Journey to the End of the Millennium, 2005) by Josef Bardanashvili, to a libretto by A. B. Yehoshua.

Collaboration with Hanoch Levin

Without question, a major chapter in Ruth Dar’s professional biography is her work with playwright-director Hanoch Levin, the most admired member of the Israeli theatrical community. Dar’s first encounter with Levin’s work took place in 1972 with the play Hefetz directed by Oded Kotler at the Haifa Municipal Theater. That same year, Levin and Dar began their longstanding collaboration, which has included: Ya’akobi ve-Leidental (Ya’akobi and Leidental; Cameri, 1972); Krum (Haifa Theater, 1975); Popper (Haifa, 1976); Hotza’ah la-Horeg (The Execution; Cameri, 1979); Yisurei Iyov (Job’s Passion; Cameri, 1981); Ha-Zonah ha-Gedolah mi-Bavel (The Great Whore of Babylon; Cameri, 1982); Kulam Rotzim Lihyot (Everyone Wants to Live; Cameri, 1985); Yakish ve-Poupche (Yakish and Poupche; Cameri, 1986); Nikhna u-Menuzah (Beaten and Defeated; Cameri, 1988); and Ha-Zonah mi-Ohio (The Whore from Ohio; Cameri, 1997).

Dar played an important role in creating Levin’s unique visual “look,” not only because “Levin comes without any preconceived visual concept” (as Dar remarked in a newspaper interview; Haaretz, March 22, 1989) but primarily because with Levin, “the visual aspect is the final version of the play” (in the words of actor Yosef Carmon; Haaretz, March 22, 1985). Dar sees the influence of Levin the director on her work in the attribute of conciseness, that is, “the ability to create an [entire] atmosphere using one effect” (Haaretz, March 22, 1989). This was already evident in the production of Ya’akobi and Leidental, which took place on a small stage with three chairs and a low purple screen stretching the length of the stage. Alongside the screen, yet part of it, was the suggestion of a window frame. The characters came out from behind the screen, and appeared in the window behind it. The design space was knowingly theatrical and created a cabaret-like setting for the world being presented.

Several images from Dar-Levin collaborations are engraved in the collective memory of Israeli theater, for example from the play Job’s Passion—a work about cruelty and evil, and one of Levin’s first spectacles. Raised scenic elements were placed within the “empty space” of the Cameri Theater’s huge stage; sitting upon them were the well-fed, contented guests of Job. The black and gold costumes, heavy stage makeup, crowns of gold on yellow- and orange-colored wigs, and the large gold jewelry on the necks of the actors combined to create a baroque effect. The space was filled at first with melodramatic beggars, and later with the bodies of Job’s dead children, laid out next to one another in front of the vacant eyes of the guests, who left the stage one by one. At that point, the piece of scenery on which they had been sitting was revealed to be a mound of gray boulders. The rocks functioned on two levels, as both an image of headstones for the children’s bodies and a horrifying visual symbol of destruction.

What stands out in the memory from Everyone Wants to Live, with its narrative echoes of “everyman,” are the costumes of the party guests, which gave them the appearance of strange birds; empty sleeves attached to the garments of the angels of death flapped around continually as a substitute for the more-familiar angels’ wings. The image of fourteen empty coats flying in a blue sky, projected on a rear screen as the final image of the play, made a mockery of the human instinct for survival.

In Yakush and Poupche, seven lampposts, each of them with six spotlights, symbolized the journey from place to place—which turns out to be the same place all along. When the characters reached the “town,” one light on one post was lit. Another “town” was symbolized by a different post and a different light, while the “palace” was indicated by all of the spotlights lit at once. The abstract space representing all places and all times was completed by the play’s characters—poor people wearing piles of heavy clothing.

Ruth Dar left a lasting imprint on the visual aspects of Hanoch Levin’s dramatic world with its elements of theatricalized death and tangible portrayal of absence. In the wake of his death in 1999, one cannot read his poetic oeuvre without relating to the cumulative visual “baggage” of their collaborative efforts.

Ben-Meir, Orna. “Visual Iconography in the Work of Ruth Dar for the Plays of Hanoch Levin.” In Ha-Cameri: Teatron shel Zeman ve-Makom, edited by Gad Kaynar, Eli Rozik and Freddie Rokem. Tel Aviv: 1999.

Israel Documentation Center for the Performing Arts. Tel Aviv University. Archive file no. 30.4.5.

Shefi, Meira. “Portfolio: Ruth Dar, Set and Costume Designer.” Teatron: The Israel Quarterly for Contemporary Theater 1 (2000): 60–67.