Marti Friedlander

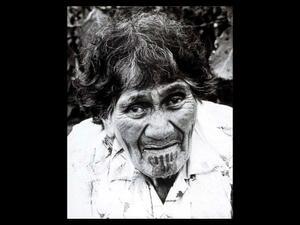

Marti Friedlander migrated to New Zealand at the age of 30, becoming a professional photographer there and quickly making a strong impact nationally with her published work in the 1960s and 1970s. From the 1990s her photographs were exhibited much more widely in art galleries. The large retrospectives in 2001 (which travelled the country), 2009, and 2020 (portraits) established her importance and influence on the medium in New Zealand. Her work is regarded highly internationally, from her exhibition at London’s Photographers Gallery in 1975 and most notably by her Moko: Maori Tattooing in the Twentieth Century (text, Michael King) featuring elderly Maori women with chin tattoos. Moko was first published in 1972 and went through five subsequent editions. Friedlander was also a major benefactor to the arts and arts education.

Introduction

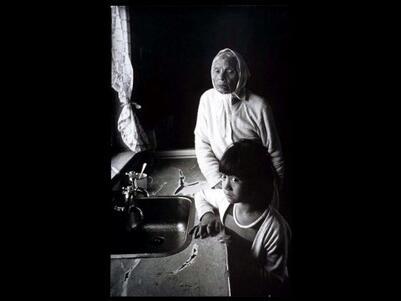

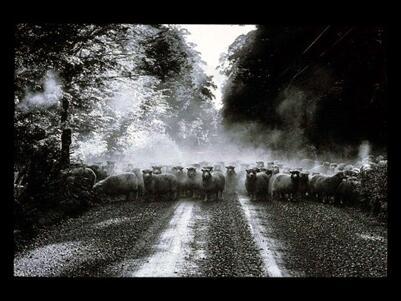

Marti Friedlander’s work was central to New Zealand’s social and cultural life beginning in the early 1960s. She was massively influential both in the development of photography as an artistic practice in New Zealand and in the documentation of the country’s social and cultural life notably through her photographs of elderly Maori women (kuia) with traditional facial tattoo (moko), in Moko: Maori Tattooing in the 20th Century (1972); her portraits of vintners, immigrants, artists, writers, actors, craftspeople and musicians; her “street” photography, and her brilliant picturings of diverse aspects of New Zealand culture and society, suburban, small-town, and rural during periods of radical social change. Her images were extensively published in magazines, newspapers, and books. Many of her images have played prime roles in shaping how places, people, and events in New Zealand are known and understood.

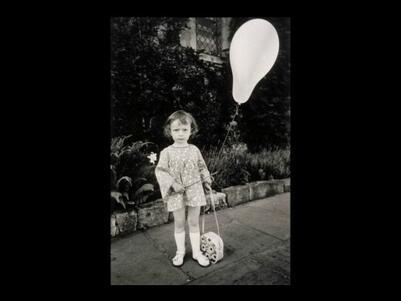

Friedlander’s first exhibition was in 1966: portraits of children, which revealed astute insights into the complexities of childhood. Though her photographs appeared frequently in group exhibitions from the 1970s on, one-person shows were few until her massively popular Auckland Art Gallery retrospective in 2001, which toured the country until 2004. Shirley Horrocks’ documentary film The Passionate Eye (2004), which won awards in festivals in Germany, Italy, Israel, the United States, Canada, and Australia, also expanded the audience for her photographs.

Early Life & Training

Friedlander was born on February 20, 1928, in Mile End in the then-economically poor East End of London. She and her older sister, Ann, were the daughters of Sophie and Philip Gordon, Russian-Jewish immigrants who were unable to cope and disappeared. Initially Friedlander was placed in the London County Council’s Ben Jonson Home, reportedly a grim institution in Bethnal Green. Fortunately she was rescued, and the sisters re-united in 1933 at the Norwood Orphan Aid Asylum, a Jewish orphanage in southwest London.

Friedlander arrived at photography by accident. After having won a Trade Scholarship at the age of thirteen to train as a dressmaker, she found the course already full, with only vacancies in the “trade” of photography. She studied photography at Bloomsbury Technical School and art for a further year at the excellent Camberwell School of Art in South London.

Beginning in 1946, Friedlander was an assistant to Douglas Glass and then Gordon Crocker, leading photographers in their shared Kensington studio. The technical skills she acquired were invaluable. New Zealand-born Glass (1901-1978), the Sunday Times portrait photographer from 1949 to 1961, observed that she could produce an image from a blank negative.

In London in1957, Friedlander married New Zealander Gerrard Friedlander, born Gerhard in Berlin in 1930. He had emigrated with his family first to the British Mandate of Palestine in 1935, and then in 1937 to New Zealand, not an easy country for refugees from Nazism to enter. The Friedlanders moved to New Zealand in early 1958; except for an extended trip to England, Europe, and Israel in 1962 and 1963, their home for the next nine years was Henderson, an agglomeration of rural holdings and new suburb on the edges of a rapidly expanding Auckland.

Early Career

While Friedlander took many photographs during her travels, she arrived in New Zealand with no plans for a career as a photographer. That she became a professional photographer happened incidentally. Her first photographs published in New Zealand were for the arts quarterly Landfall in 1959-1960. Her next published photographs appeared in the entertainment magazine Playdate in the early 1960s, including, for example, images of English crooner Cliff Richard performing in Auckland’s St. James Theatre. Historian and friend Dick Scott was the editor of The Wine Review, which began featuring her photographs in 1964. Beginning in 1965, the important New Vision art gallery in Auckland, founded by Dutch immigrants Kees and Tine Hos, began commissioning portraits of artists and potters, as well as exhibition installation shots, from Friedlander for their brochures. By the mid-1960s, her career was well on its way.

As was common at the time, Friedlander’s photographs first became widely known through print publications. The variety of publications for which she did work attests to her broad range in subjects, themes, and genres. Besides those already noted, they included the New Zealand Herald, the Auckland Star, the Weekly News, the New Zealand Listener, the Town Planning Quarterly, Thursday (a proto-feminist women’s magazine of the late 1960s and early 1970s), and the later militantly feminist Broadsheet, as well as prominent arts periodicals Art New Zealand, Islands, New Argot, and Music New Zealand.

Photo-Books

Friedlander’s photo-books were ground-breaking. Moko: the art of Maori tattooing in the twentieth century (text by Michael King, 1972) featured elderly Maori women with traditional chin tattoos, when this was no longer practiced. Several leading publishers rejected Moko, claiming that few people would be interested and it was not financially viable. Yet Moko had many subsequent editions through to 2019. Larks in a Paradise: New Zealand Portraits (text by James McNeish, 1974) was also a “hit.” Some people criticized it for its supposedly negative view of New Zealand, but that was not Friedlander’s intention, and others aptly praised the photographs for their humanist celebration of the individuality and distinctiveness of the country’s people. Her next book, Contemporary New Zealand Artists: A – M (text by Jim and Mary Barr, 1980) included her first published color photographs. It is now a collector’s item.

A rush of books followed in the twenty-first century: Marti Friedlander Photographs (2001), Dick Scott’s, Pioneers of New Zealand Wine (2002), Leonard Bell’s Marti Friedlander (2009 and 2010), Self Portrait: Marti Friedlander (with Hugo Manson, 2013), and Claire Dunleavy’s Waiheke Island: A World of Wine (2017). A book of Friedlander’s portraits of artists, writers, potters, theater people and dancers, musicians and architects will be published in late 2020. Her photographs are prominent in numerous other books; their subjects and concerns are diverse – old age, sociology, women high achievers, tourism, Fiji and Tokelau Islands, biographies, monographs on artists and exhibition catalogues, and authors’ photographs on the dust jackets of novels and volumes of poetry.

A Photographer of New Zealand

Friedlander was a key photographer in New Zealand, influencing younger practitioners through the quality of her work in several genres: portraiture in various modes, “street” photography, photo-journalism and photo-essays, architectural and landscape work, and photo-books. That she collaborated closely with leading historians, novelists and poets, anthropologists and other academics, journalists, artists, and musicians means that her work impacted far beyond an audience of photo-aficionados.

Friedlander was highly intelligent, impassioned, and coolly reflective. Photography enabled her to explore New Zealand society and people. Portraits were her prime strength. They reveal an extraordinary skill in visualizing qualities of personality and temperament. Her picturings of elderly Maori women not only document their subjects with intense, understated sympathy, but also helped Friedlander feel more at home in New Zealand. Her drive to photograph New Zealand’s artists, writers, and other creative people was motivated by the view that they were under-recognized and under-valued. As an immigrant, she was able to visualize aspects of social relations that most New Zealand-born did not see, or did not want to see. For instance, an image (1967) of a solitary man in a crowded small-town pub, his fist clenched, explosive with latent tension, is a riveting portrait of both an individual and a widely shared social condition. Friedlander’s 50 years photographing artists, writers, musicians, et al constitute a history of the radical changes in New Zealand culture, from a time when the arts had little status in mainstream society, to the early twenty-first century, when they are treasured and the amount of high quality creative work is prolific for a country with a small population.

Friedlander’s photographs of women, especially those in Moko and her many portraits of women artists, writers, potters, musicians and actors, in particular but not only in the 1960s and 1970s, embody her feminism. It is striking how many she photographed at a time when, with some exceptions, female artists and writers were routinely consigned to secondary positions, regarded as minor and patronized or dismissed by male critics and fellow practitioners. Friedlander was not one to passively accept subordination. She simply ignored traditional attitudes about “women’s place” and went her own fiercely independent way.

Overall Friedlander’s photographs are insightful picturings of places and their inhabitants, in particular people’s relationships with one another, whether in New Zealand, Israel, England, or Fiji and Tokelau in the Pacific. Her images attest to her intense engagements with various locations, such as deserts, rural environments, vineyards, beaches or city streets, and the people, events, and behaviors within them. Empathy characterizes Friedlander’s photographs, whether, for example, her 1968 portraits of the elderly Rauwha Tamaiparea, an isolated presence in the mostly abandoned Maori settlement of Parihaka, a troubled-looking child clutching a balloon, or an artist who seems riven by anxiety.

Philanthropy & Legacy

Friedlander was a bountiful benefactor. All 160 or so large prints from her 2001 retrospective exhibition were gifted to the Auckland Art Gallery, while the vintage Moko suite of images went to Te Papa Tongarewa/Museum of New Zealand. In 2008 she and Gerrard instituted a biannual award to a promising photographer. From 2016, annual grants to the Auckland University Press have assisted the publication of visual arts books. In 2019 the Marti Friedlander Lectureship in Photography in the School of Humanities at the University of Auckland and a Friedlander-funded program to assist less advantaged public secondary schools to purchase camera equipment for their photography courses were instituted.

A large archive of Friedlander’s photographs, negatives, and personal papers is held on loan at the Auckland Art Gallery, a treasure trove for researchers, social historians, and artists. Its cultural and social value was recognized when it was elevated to the UNESCO Memory of the World New Zealand Register in November 2017, the first photographic archive in Australasia so honored. In 1998 Friedlander was made a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to photography. She was also an Arts Foundation Laureate, just one of twenty at any one time. The honor that she valued most came just a month before she died on November 14, 2016, the conferral of an honorary Doctorate by the University of Auckland. Friedlander had come a long way from Mile End.

Selected Works by Marti Friedlander

Self-Portrait: Marti Friedlander (with Hugo Manson). Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2013. (With Hugo Manson.)

Marti Friedlander Photo-books:

Moko: Maori Tattooing in the Twentieth Century (with Michael King). Wellington: Alister Taylor, 1972; Auckland: David Bateman 1992, 1999, 2008 & 2019.

Lark in a Paradise: New Zealand Portraits (with James McNeish). Auckland & London: Collins, 1974.

Contemporary New Zealand Painters A-M (with Jim and Mary Barr). Martinborough: Alister Taylor, 1980.

Pioneers of New Zealand Wine (with Dick Scott). Auckland: Reed/Southern Cross, 2002.

Waiheke Island: A World of Wine: The People behind the Labels (with Clare Dunleavy), Auckland: Beatnik Publishing, 2017.

Bell, Leonard. Marti Friedlander. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2009 & 2010.

Bell, Leonard. Marti Friedlander, Portraits of the Artists. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2020.

Brownson, Ron (ed.). Marti Friedlander: Photographs. Auckland: Auckland Art Gallery and Bateman Books, 2001.