Katherine M. Cohen

Katherine M. Cohen.

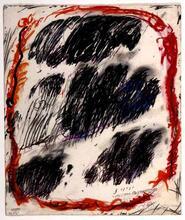

Photograph from Cohen's "Life of Artists," in Mary Kavanaugh Oldham Eagle's The Congress of Women: Held in the Woman's Building, World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, USA, 1893. Chicago, Ill: Monarch Book Company, 1894.

Katherine M. Cohen created sculptures that explored Jewish themes and earned respect in both American and European circles. Cohen studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and worked at the Art Student League in New York before opening her studio. Cohen’s commissions included creating the seal of Gratz College and sculpting portrait busts of prominent Jews. She also chaired the choir of Mikveh Israel. In 1893, Cohen traveled to the Chicago World’s Fair, where she spoke on the lack of support for the arts in America. Cohen traveled to Paris to work under prominent sculptors and was elected an honorary member of the American Art Association. Cohen resisted modernist and cubist trends, preferring more traditional approaches, and enjoyed great success for her ambitious works.

Although few Jews were sculptors in nineteenth-century America, in part due to the biblical prohibition against creating graven images, Katherine Cohen, a sculptor from Philadelphia with elite academic training, exhibited figurative works, often of Jewish subjects, in an era when women and Jews achieved slight renown in the art world.

Early Life and Family

Katherine Cohen, the youngest of four children, was born in Philadelphia on March 18, 1859, to immigrant parents, Henry Cohen of London and Matilda (Samuel) Cohen of Liverpool. As a child, she had a private tutor and later attended the Chestnut Street Seminary. Cohen’s art training lasted several years. She studied first in Philadelphia at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts under painter Thomas Eakins, and then worked at the Art Students League in New York City as an assistant in the atelier of Gilded Age sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. In 1884, she opened her own studio in Philadelphia. In 1887, she went to Paris to work under sculptors Puech and Mercie, remaining in Europe for several years. While in Paris, she was elected an honorary member of the American Art Association. The academic jury chose her life-size sculpture The Israelite for the 1896 Paris Salon, a definitive sign of her arrival as an artist.

Art Career

In 1893, on a visit to the United States, Cohen spoke on the “Life of Artists” at the Women’s Pavilion at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Her speech described the daily struggles and triumphs of artists, defended their way of life, and commented on the potential of art in the United States. “When we arrive at the point that American art is better than anything we can get in Europe,” she said, “then we shall stay at home to study. … We can all of us help the quick realization of this, if we encourage our boys and girls to cultivate their artistic tastes instead of scoffing at them as impractical and never likely to make them rich.”

Comfortably situated in the community of Philadelphia’s Jewish elite, the Cohen family was highly respected, even powerful, in the city’s secular establishment. Before she left for Europe, Cohen illustrated A Jewish Child’s Book for kindergartners, published by the Jewish Publication Society. Her book was one of the first Jewish children’s books to be printed in color. She also chaired the choir at Mikveh Israel, the prominent Philadelphia synagogue. Her mother founded the Committee of Thirteen, which organized the art exhibit at Philadelphia’s 1876 centennial celebration. Her sister Mary was an author on Jewish subjects and a community organizer who addressed the Jewish Women’s Congress at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Her brother, Charles, a merchant, was the president of the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce and a trustee of Gratz College.

Not surprisingly, Cohen found many patrons to support her. Among her commissions were the design of the seal of Gratz College and portrait busts of prominent Philadelphia Jews, including Judge Mayer Sulzberger and businessman/philanthropist Lucien Moss. She further illustrated a strong choice of Jewish themes with her ambitious multifigured sculpture Vision of Rabbi Ben Ezra. However, her success did not necessarily mean she subscribed to cutting-edge developments of the contemporary art of her period. True to the tenets of academic classicism, she had little tolerance for the modern art emerging at the turn of the century and likened futurist and cubist depictions of a human eye to “a horrible distorted fish.”

Legacy

Katherine Cohen died in Philadelphia in December 1914 age fifty-five. Her 1893 Women’s Pavilion speech evidenced her lifelong pursuit of and commitment toward art in which she stated, “An artist’s chief grief is that life is too short for him to accomplish what he wants to do even in his own special line of work, and this is equally true of woman, for talent knows no sex.”

AJYB 6 (1904–1905): 76, 17 (1915–1916): 219.

AJA (April 1963): 48.

American Jewish Historical Society Quarterly (Summer 1995).

Cohen, Katherine M. Letters. Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

JE.

UJE.