Madeline Brandeis

Born in San Francisco in 1897, Madeline Brandeis was a noted children’s book author and pioneer filmmaker. In 1918, she married department store heir, E. John Brandeis and had one daughter. Financed by her husband, she produced her first silent film geared towards and featuring children. After their divorce, she continued producing well-received films outside the mainstream Hollywood studios. Her career reflected changes in the film industry, from egalitarian and inclusive to a male-dominated business. Her Children of All Lands series was recognized as a contributor to world peace by the League of Nations in 1929. Until her untimely death in 1937, Brandeis travelled the world in search of stories to tell, while aiming the lens of her camera at the lives of her characters.

In her dedication to her 1929 book, The Little Swiss Wood-Carver, noted children’s author and pioneer filmmaker Madeline Brandeis sounded her unique multicultural note: “To every child of every land,/Little Sister, Little Brother,/As in this book your lives unfold,/May you learn to love each other.” Until her untimely death at the age of 39, Brandeis traveled the world in search of stories to tell, while aiming the lens of her camera at the lives of her characters.

Early Years

Madeline (Frank) Brandeis was born on December 18, 1897, in San Francisco, to Albert and Mattie (Ehrman) Frank and attended the elite Miss Burke’s School there. She married E. John Brandeis, heir and manager of the J.L. Brandeis and Sons department store in Omaha, Nebraska, on January 28, 1918; they had one daughter, Marie Madeline.

Producer and Filmmaker

Financed by her wealthy husband, Brandeis wrote, directed, and produced her first silent film, The Star Prince, in Chicago in 1918 with an all-child cast. In this fairy-tale-like story, a woodcutter discovers a baby in the ruins of a shooting star and adopts the child, who grows up to be the Star Prince, played by child actor Zoe Rae on loan from Universal Studios. Brandeis’ next film was a love story set in Omaha, Nebraska, When East Meets West (1919), sponsored by the Omaha Chamber of Commerce.

Divorced in 1921 and with a $400,000 settlement in lieu of alimony, Brandeis moved back to California, settling in Hollywood. She was inspired to continue producing feature-length films geared towards children after meeting director Renaud Hoffman. Under Hoffman’s direction and with Brandeis’ capital, Not One to Spare, based on a famous poem, was released in 1924 to critical acclaim. Produced at a cost of $6,000, it grossed nearly $100,000 by 1929. The Shining Adventure (1925) was produced the following year, under the banner of her newly formed production company Madeline Brandeis Productions.

In 1927, Brandeis produced the comedic Young Hollywood, featuring the children of well-known film stars, suggesting that Brandeis had connections within the burgeoning Hollywood film industry. Hollywood would begin to phase out silent films, the medium in which she worked, with the introduction of the first commercially successful “talkie,” The Jazz Singer (Warner Brothers) that same year.

Women in the Early Film Industry

Brandeis’ career reflects the structural changes in the American film industry in the early part of the twentieth century. As a new medium, filmmaking was egalitarian and inclusive. Women were producers, directors, film editors, and cutters, as well as stars. Because early film ventures were deemed risky and a passing fad, the field was wide open to anyone who wanted to take a gamble. Barred from more mainstream occupations, Jews also flocked to the movie business. As the market for movies grew and large Hollywood studios began to dominate the industry, women were pushed out of the production side of the business.

By the 1920s, women producers like Brandeis were an exception, and, indeed, she operated outside mainstream Hollywood studios. Indeed, in an interview entitled “Woman Makes Films for Fun” (Los Angeles Times, May 16, 1926) she felt a need to downplay her work as a “pastime.”

Cultural Ambassador

American children’s book author and filmmaker Madeline Brandeis’s film “The Little Dutch Tulip Girl,” 1928.

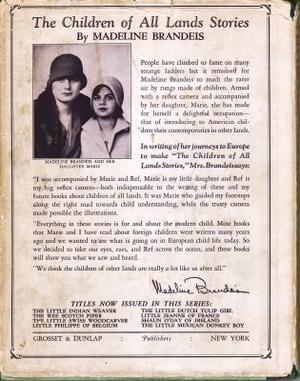

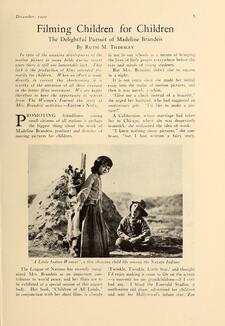

Beginning in 1928, Brandeis launched, under the Pathe label the Children of All Lands educational series of films, with accompanying children’s books for use in the elementary school classroom. The Pathe company covered production costs, while Brandeis did everything from directing to cutting the final takes. Taking her trusty reflex camera (nicknamed “Ref” in the preface to her 1929 book The Little Swiss Woodcarver) and accompanied by her young daughter, Brandeis traveled to Europe and across North America, hiring local crews and casts to film picturesque one-reel shorts about the lives and culture of “modern” children.

The first film in the series, The Little Indian Weaver (1928), is set in the American Southwest. A Navajo child and her mother teach a kind young “American” about her culture. The film shows sensitivity to the ways in which language is used to demean other cultures, with the Navajo mother instructing her visitor never to use the slur “squaw” for a female Native American.

In 1929, the League of Nations recognized the author, producer, and director as an important contributor to world peace. Exemplifying the possibility of “world friendship among children” Brandeis’ films were exhibited at a special session of the League (Tilesdley, “Giving Children a Chance,” Screenland, 1929).

Children’s Author

Brandeis’ focus shifted from filmmaking to writing as she published additional volumes for the Children of All Lands Series. In a similar vein, she began a new series, Children of America Stories, published by Grosset and Dunlap. The publication of dozens of her titles for children and adolescents, including the novel Six Face the World (1938), reflected the explosion in the quantity and quality of books for children that began in the 1920s and 1930s.

Brandeis’ work does not deal overtly with her own Jewish identity, although the themes of respect for different cultural and national heritages and of passing down family traditions and values resound in her books. In The Little Swiss Wood-Carver, the poor mountain boy of Switzerland keeps the memory of his artist father alive in his own work; in The Little Spanish Dancer (1931), the young dancer is reminded of how her Spanish foremothers, despite persecution, secretly took their daughters into the dim light of caves in order to teach them the art of the dance.

Later Years

Brandeis married a second time, to Dr. Joseph A. Sampson, on October 5, 1933, and the couple lived in New York City. A June 15, 1937, article in The New York Times recounts that the New York writer and her sixteen-year-old daughter were seriously injured when their car overturned near Gallup, New Mexico, while they were traveling from New York to California. Brandeis died of her injuries two weeks later, on June 28, 1937. Her daughter, Marie Madeline Ehrman (Brandeis), died in 1973.

Rediscovery of Her Contributions to Film

Despite Brandeis’ cinematic achievements, her obituary in The New York Times notes only that she was a New York author. Recent work into the untold story of early women pioneers in film has brought attention to her motion picture work. An essay by Radha Vatsal in 2013 for Columbia University’s Women Film Pioneers Project places Brandeis in the context of the late silent film era. Her first film, The Star Prince, is included in Early Women Filmmakers: An International Anthology DVD (Flicker Alley US 2017), which highlights the contributions of fourteen important women in cinema's early years.

Suzanne Oshinsky is a writer, educator, and more recently a political organizer, living in Maryland with her husband, two children and two cats. A graduate of the all women’s Barnard College of Columbia University in New York, she also earned her master’s degree in Hebrew Literature and Jewish Studies from the University of California, Berkeley.

Selected Works by Madeline Brandeis

Films

The Star Prince (1918), included in Early Women Filmmakers: An International Anthology DVD (Flicker Alley US 2017)

When East Meets West (1919)

Not One to Spare (1924)

The Shining Adventure (1925)

Young Hollywood (1927)

Children of All Lands Series (1928-1929, Pathe)

Books

Adventures in Hollywood. New York: Coward-McCann, 1937.

The All Wrong Book. Los Angeles, San Francisco: Suttonhouse, 1932.

Jack of the Circus. Chicago: The Reilly & Lee co., c. 1931.

Little Anne of Canada. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1931.

Little Carmen of the Golden Coast. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1935.

Little Dutch Tulip Girl. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1929.

Little Eric of Sweden. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, c. 1938.

Little Farmer of the Middle West. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, c. 1937.

Little Indian Weaver. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1928.

Little Jeanne of France. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1929.

Little John of New England. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, c.1936.

Little Mexican Donkey Boy. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, c. 1931.

Little Phillipe of Belgium. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1930.

Little Rosa of the Mesa. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, c. 1935.

The Little Spanish Dancer. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1936.

Little Swiss Woodcarver. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1929.

Little Tom of England. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, c. 1935.

Little Tony of Italy. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, c. 1934.

Mitz and Fritz of Germany. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, c. 1933.

Shaun O’Day of Ireland. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1929.

Six Face the World. Publisher unknown. c. 1938

Wee Scotch Piper. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1929.

Yankee Doodles Adventures, An American Fairy Tale. Los Angeles, San Francisco: Suttonhouse, c. 1932.

Gaines, Jane, and Radha Vatsal. “How Women Worked in the US Silent Film Industry.” Women Film Pioneers Project, Columbia University. https://wfpp.columbia.edu/essay/how-women-worked-in-the-us-silent-film-industry/

Hutchinson, Pamela. “Where to Begin with Early Women Filmmakers.” BFI, June 10, 2019.

https://www2.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/features/where-begin-early-women-filmmakers

Mahar, Karen Ward. Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood by Karen Ward Mahar. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

Siede, Caroline. “Women Pioneered the Film Industry 100 Years Ago. Why Aren’t We Talking About Them?” Bustle, January 2020.

https://www.bustle.com/p/meet-the-women-who-pioneered-the-film-industry-19421012

“The Star Prince (1918): A Silent Film Review,” Movies Silently, April 21, 2019)https://moviessilently.com/2019/04/21/the-star-prince-1918-a-silent-film-review/

Tildesley, Ruth M. “Filming Children for Children: The Delightful Pursuit of Madeline Brandeis.” The National Review Board, December 1929.

Tildesley, Ruth M. “Giving the Children a Chance.” Screenland, May-Oct 1929.

Vatsal, Radha. “Madeline Brandeis.” Women Film Pioneers Project, Columbia University, 2013. https://wfpp.columbia.edu/pioneer/ccp-madeline-brandeis/

“Woman Makes Films for Fun.” Los Angeles Times, May 16, 1926.

“Woman Author Injured.” The New York Times, June 15, 1937.