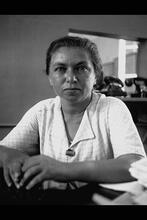

Bertha Badt-Strauss

The life of writer Bertha Badt-Strauss spanned two centuries and two continents. Born in Breslau, Germany, in 1885, the religious Badt-Strauss, who promoted a return to Judaism as well as the cultural Zionist "Jewish Renaissance," lived the last thirty years of her life in the southern United States. She is shown here in Breslau, circa 1910.

Institution: Albrecht B. Strauss.

A religious German-Jewish writer, intellectual, and ardent Zionist, Bertha Badt-Strauss was one of the first women to earn a doctoral degree in Prussia. She became involved in the “Jewish Renaissance” cultural movement; unlike other German intellectuals of the movement, she believed the failure of German Jews to assimilate and their subsequent return to Judaism was a step in the right direction. Badt-Strauss was a prolific writer, publishing hundreds of articles in Jewish and non-Jewish publications over the course of her lifetime, as well as several short stories, a novel, and a collective biography of Jewish women. She sought to complicate the simplistic image of the Jewish woman portrayed by male intellectuals by illuminating the diverse experiences of Jewish women past and present and by inviting women to take active space in the creation of Jewish community. After Badt-Strauss’s family left Germany for the United States in 1939, she continued writing for several America-Jewish publications.

Born in Breslau on December 7, 1885, Bertha Badt-Strauss, who died in Chapel Hill, North Carolina on February 20, 1970, lived in two centuries and on two continents. Bertha was descended from a well-known family of Jewish scholars. Her father, Benno Badt (1844–1909) was a philologist and teacher and her mother, Martha (née Guttman, 1858–1929), was a teacher.

Writing Career & Involvement in the Jewish Renaissance Movement

Bertha Badt studied literature, languages, and philosophy in Breslau, Berlin, and Munich and was one of the first women to earn a doctoral degree in Prussia with a thesis entitled “Annette von Droste-Hülshoff, ihre dichterische Entwicklung und ihr Verhältnis zur englischen Literatur” (Annette von Droste-Hülshoff: her poetic development and relation to English literature). She worked as a researcher and publicist.

Like her brother Hermann Badt (1887–1946) and her sister Lotte Prager (1891–1957), Badt-Strauss became an ardent Zionist and was deeply involved in the cultural movement called “Jewish Renaissance.” She contributed to the Jewish Renaissance’s aim of creating a Jewish community with a special Jewish culture. With her husband, Bruno Strauss (1889–1969), a teacher and expert on Moses Mendelssohn, she lived in Berlin from 1913. In 1921 their only son, Albrecht, was born. Shortly afterwards Badt-Strauss fell ill with multiple sclerosis, but she nevertheless published numerous articles in Jewish publications such as the Jüdische Rundschau, Der Jude, the Israelitische Familienblatt, the Blätter des Jüdischen Frauenbundes and Der Morgen, and also in such leading non-Jewish newspapers as the Vossische Zeitung and the Berliner Tageblatt. She co-edited the first scientific edition of Annette von Droste-Hülshoff’s works and translated and edited volumes of works by Gertrud Marx, Profiat Duran, Leon da Modena, Süßkind von Trimberg, Heinrich Heine, Rahel Varnhagen, Achim von Arnim, Louise von François, William Rosenau, Fanny Lewald and Moses Mendelssohn. She contributed to the Jüdisches Lexikon and the Encyclopaedia Judaica and wrote short stories, an unpublished biography of Elise Reimarus, an installment novel, a collective biography of Jewish women, and, together with Nachum Tim Gidal, a picture book. Her last editorial work in Germany (together with her husband) was an anthology of letters by Hermann Cohen.

While Badt-Strauss was a religious Jew whose entire private life took place within a Jewish microcosm, she participated in the German women’s movement, wrote about German literature, and published in German newspapers and magazines. Alleged and real assimilationists such as Moses Mendelssohn and Rahel Varnhagen were among those about whom she wrote a great deal. Many other Jewish intellectuals who were part of the Jewish Renaissance, such as Jacob Wasserman, Franz Werfel, and Kurt Tucholsky, dealt with what they perceived as their “failure” as Germans during World War I by portraying the assimilated German Jew as highly dislikable, but they were unable to present an appealing alternative. Badt-Strauss, on the other hand, sought to reinterpret the (mostly resigned) return of prominent Jews to Judaism as a self-determined step in the proper direction. Thus she not only brought the apostates back into the Jewish community but simultaneously offered positive role models with which to identify in place of self-castigation.

Engagement with Jewish Women

Badt-Strauss’ intensive engagement with Jewish women stemmed from her aim of creating positive role models and only partially from a feminist consciousness. The predominantly male protagonists of the Jewish Renaissance had a very simple image of the Jewish woman: the bad Western European Jewess versus the good East European Jewess. As a religious German-Jewish woman, Badt-Strauss was not only unable to find herself in either of these images but also considered this strategy not very useful in motivating women to rethink their attitude towards Judaism. In her articles and books she preferred to present a series of diverse Jewish women from past and present without judging their lifestyle. Her only specification was the return to Judaism and eventually to Erez Israel. While not specifying the manner of this return or what role woman had to play in Judaism and in the Yishuv, she invited women to take part in the creation of a Jewish community, even if they had not previously seen their space in this context because of a rigid male conception of Jewish femininity.

Immigration to the United States

Badt-Strauss was highly successful with this individual interpretation of a Jewish Renaissance; her list of publications includes hundreds of articles and many editions. However, it is unknown whether her work affected German Jewry in the way intended. The takeover of the National Socialists brought the Jewish Renaissance to an end before its effects could unfold.

Although one might have expected a Zionist such as Badt-Strauss to emigrate to Palestine, she in fact left Germany in 1939 for the United States. Partly this was because her husband, who was not a Zionist, did not want to live in Palestine, nor did he believe he would find work there as a teacher of German and history. In fact, he received a job offer from the U.S., where he became a professor at Centenary College in Shreveport, Louisiana. Badt-Strauss continued writing for several American-Jewish papers such as the Aufbau, The Jewish Way, The Menorah Journal, The Reconstructionist, The National Jewish Monthly, the Hadassah Newsletter and Women’s League Outlook, and published a biography of the American Zionist Jessie Sampter.

Selected Works by Bertha Badt-Strauss

Annette von Droste-Hülshoff, ihre dichterische Entwicklung und ihr Verhältnis zur englischen Literatur. Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer, 1909.

Rahel und ihre Zeit. Briefe und Zeugnisse. Selected by Bertha Badt, München: E. Rentsch, 1912.

Marx, Gertrud. Jüdische Gedichte. Selected by Bertha Badt, Berlin: Jüdischer Verlag, 1919.

As Bath Hillel. In Bene Berak und andere Erzählungen. Berlin: Jüd Verlag, 1920.

Die Lieder des Süßkind von Trimberg. Edited and translated by Bertha Badt, Berlin: Verlag fur Judische Kunst und Kultur, 1920.

Von Droste-Hülshoff, Annette Sämtliche Werke. Together with Bertha Badt-Strauss and Kurt Pinthus edited by Karl Schulte Kemminghausen. 4 Vol., München: 1925–1930.

Mendelssohn, Moses. Der Mensch und das Werk. Zeugnisse, Briefe, Gespräche. Edited and introduced by Bertha Badt-Strauss, Berlin: Heine-Bunde, 1929.

Jüdinnen. Berlin: J Goldstein, Jüdischer Buchverlag, 1937.

Cohen, Hermann. Briefe. Selected and edited by Bertha and Bruno Strauss, Berlin: Bücherei des Schocken Verlags, 1939.

White Fire. The Life and Works of Jessie Sampter, New York: Reconstructionist Press, 1956.

Steer, Martina B. Bertha Badt-Strauss (1885–1970). Eine jüdische Publizistin. Frankfurt/Main: Campus Verlag, 2005.

Hahn, Barbara. “Bertha Badt-Strauss (1885–1970). Die Lust am Unzeitgemäßen.” In Frauen in den Kulturwissenschaften, edited by Barbara Hahn, 152–164. München: C.H. Beck, 1994.