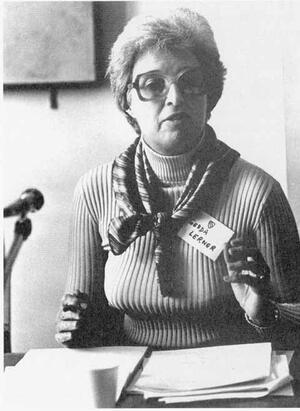

Remembering Gerda Lerner: The "Mother" of Women's History

Gerda Lerner, pioneer in women’s history, remarkable public intellectual, and life-long activist, died this week in Wisconsin at the age of 92. A member of JWA’s Academic Advisory Council, she was enthusiastic about our mission of chronicling and transmitting the history of Jewish women. No historian was more identified with the field of women’s history. Receiving her Ph.D. at the age of 46, she wrote a series of groundbreaking books in which she almost singlehandedly created a conceptual framework for the field.

Her leadership extended beyond theory to practice: she institutionalized women’s history when she created the nation's first graduate program in the field at Sarah Lawrence College and played a major role in making women’s history a subject of interest to the general public. The idea for Women’s History Week (now the popular Women’s History Month) grew out of an institute she organized in 1979. “Women’s history is women’s right,” she said, “an essential, indispensable heritage from which we can draw pride, comfort, courage, and long range vision.”

Elsewhere on JWA:

- Encyclopedia of Jewish Women: Gerda Lerner

- "Jewish Women and the Feminist Revolution"

- Gerda Lerner and Women's History Month

Elsewhere on the Web:

She wrote important, marvelously readable books beginning with her first, The Grimke Sisters from South Carolina, published in 1967. Among her other seminal works are the anthologies, Black Women in White America and The Female Experience; a collection of essays, The Majority Finds Its Past; two volumes on the development of patriarchy and women’s resistance to it, The Origins of Patriarchy and The Creation of Feminist Consciousness; her autobiography, Fireweed; and essays reflecting on her life and work, Why History Matters and Living with History/Making Social Change.

Lerner did not connect her heritage as a Jewish refugee to her work in women's history until fairly late in her life. In the early 1990s, I asked if she would come to a conference I had been planning at Brandeis on Jewish women’s history. I suggested that she might want to speak on how being Jewish might have influenced her work as a historian. At first, she answered that she had "never given it a moment's thought." But the question prompted her to reflect on a connection she had hidden even from herself. Soon she answered, quite simply: "I am a historian because of my Jewish experience," adding that she was a historian of women and marginalized groups because she had so long been defined, and defined herself, as an "outsider." She attended the conference and gave a wonderful paper that became the seed of a powerful essay, and later of her book, Why History Matters.

"After the Holocaust," she reflected, "history for me was no longer something outside, which I needed to comprehend and use to illuminate my own life and times. Those of us who survived carried a charge to keep memory alive in order to resist the total destruction of our people. History had become an obligation." She believed that her "Jewish background and … experience with Nazi fascism disposed her toward thinking historically," and added, "my experience of being defined as an 'outsider' by others and accepting that definition for myself had predisposed me toward an understanding of 'outgroups.' " She chose race as her subspecialty within women's history since it was the major issue in U.S. history, and since African-Americans, not Jews, were the "targeted out-group.”

Gerda Lerner’s historical work and her activism shaped the field of women’s history for over 40 years. But the going wasn’t always easy. I remember in particular one occasion, probably in the early 1980s, when Harvard’s Committee on Women’s Studies invited her to give a special lecture. At that time, there was no Women’s Studies program at Harvard, and the organizers hoped that bringing Gerda Lerner to address the community would demonstrate the importance of the field. When the day came, she was introduced by a gentleman in the History Department who evidently was not a supporter of women’s history. He proceeded to say that while he knew the speaker had a distinguished record and had written “some books” about women, he hadn’t read any of them. But, he added, “she has two children.”

You can just imagine Gerda’s reaction. She came up to the podium, gave him a withering look, and replied: “For the record, my husband and I have two children. And I have written nine books.” Feisty, tough, outspoken but with a marvelous sense of humor, Gerda would never let such a slight of her beloved field, women’s history, pass without comment. She never shied away from confrontation, and her personality was as outsized as her work. She mentored hundreds of students both in and out of her classroom, always combining intellectual work with a message about the importance of activism. In Fireweed, she made an explicit connection between her work in the academy and her commitment to grassroots activism. “The style and method of my teaching, the practical extension of my academic knowledge through community outreach … came directly out of my organizational work,” she wrote. Her “lifelong commitment to social action as a political radical” in her own words helped shape her work, and it enriched incalculably the lives of her students, colleagues, and the general public. May her memory be for a blessing.

Such an amazing article! I can't even fully express how interesting it was, for a literature teacher as me. Thank you for the opportunity to get acquainted with Gerda Lerner. In my classroom, I always give topics for an argument essay, easywaypaper com, for my students. And now I feel inspired to talk with them about this great woman, and maybe suggest to write about her.

As a professor who continually tries to instill Gerda Lerner's values in students who, today, have very little sense of history, let alone women's history and social activism, I am grateful to the Archive, and Joyce Antler, for such a brilliant resumÌÄå© of the woman-icon and her career. I will treasure this concise example of powerful feminist (and Jewish) commitment, and keep it close for perpetual inspiration. Memories and blessings, they strengthen us.

My most vivid memory of Gerda is walking, with her and my wife Joan, on a street in downtown Los Angeles. (I don't recall the year, but it must have been during an AHA or OAH meeting.) As we passed by a large office building, Gerda told us she had worked there, many years before, as an X-ray technician.

Gerda Lerner was a Jewish feminist interested in race who was a member of the Communist Party and denied that she belonged to the CP until she published her autobiography, Fireweed. Jewish woman feminist--Holocaust survivor we understand--but adding in her chosen political identity, CP member, is central to understanding Gerda--her ability to speak to crowds, the intensity of her feeling about causes, the significance of African American history to her work. We should not hide from our Jewish women Communist forebears, however many their blindspots and failings, but try to understand why they embraced that particular brand of faith/calling, what it meant for them, and why it failed them and us.

In reply to <p>Gerda Lerner was a Jewish by Elizabeth Pleck

Thank you, Elizabeth, for this very astute comment. In writing Fireweed, Gerda had difficulty in confronting two painful parts of her past--one was being a Communist party member, and the other was the experience of Nazism. She toiled on the book for many years before being able to complete it. As you say, her identity as CP member is central to understanding her life and contributions. Joyce