Women as Wave, Women as Particle: The gender-racial politics of the male-female gaze

Who are you?

I mean really . . .

Who are you . . . when you are alone and no one is watching?

What is your wave state?

Indulge me a moment to (humbly) tip my hat in the direction of quantum mechanics. (It’s amazing how a blog post increases its intellectual points when the author throws around a phrase like “quantum mechanics” or “wave-particle duality.” For the science buff—hooray! For the rest of us—take heart, for what I’m about to share is simple; our foray into physics, temporary . . . and relative).

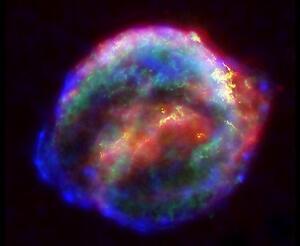

Over a decade ago (1998), researchers at the Weizmann Institute conducted an experiment that showed that an electron’s state, its way of being, is affected by the presence of an observer; and actually, the greater the “watching,” the greater the influence on the electron. In its natural state, electrons function as waves; when observed (by a detector), they change to particles.

This is old news, perhaps. But since college, when I was first introduced to this phenomenon, I wondered how it related to human behavior, gender politics, and performance.

Recently as I was exploring the JWA archives, I noticed that This Week In History spotlights the birth of Theda Bara— silent movie actress and the original “vamp,” who in all her scandalous movies played the object of desire, luring men to their ruin— and it got me thinking . . .

I’d like to share an anecdote about the male gaze. And then I’d like to share a similar anecdote, reversed.

And then I’d like to explore what it’s like to be the strong, silent type, sitting on the other side of the table.

Anecdote 1: The Control

I am a junior in college, dressed like a shlumpadinka: I wear a teal, formless sweatshirt with the neckline cut, worn over black pants—the typical uniform of a theatre kid who spends much of her day rolling around on the floor. I carry two gallons of water, one in each hand, as I navigate the busy city street that is our campus and is perpetually undergoing one construction project after another. I am hot. I am tired. The gallons of water are getting heavy. I am only minimally aware of my surroundings until I notice a construction worker in dark shades, approaching me. As we near one another, I can feel his gaze intensify, and just as we are about to pass he yells, “Nice jugs!”

I was shocked. Tickled. Impressed. This man was clever. He made a pun! How do you respond in a situation like this? Shouldn’t I be offended? But deep down, in my young, pre-sexualized self (I was a late bloomer), I loved it! And come on, you got to give the guy some credit; as far as catcalls go, that scores a ten for ingenuity. I mustered what I hoped was a righteous “Thanks!”, one that bordered on sarcasm and sincerity, if that is indeed possible. I think I pulled it off.

Anecdote 2: The Deviation / Turning the tables

A few years later, a little older, a little wiser, after having experienced a few more run-ins with ogling men and their catcalls, men who unfortunately did not possess the same punny prowess as my very first construction guy, I was pulling out of a garage downtown. Across the street a group of construction workers paraded past. It was the end of their workday, and they carried their lunch coolers. They looked tired, worn down, their white t-shirts and work boots dirty. I couldn’t resist. I just couldn’t. When would I ever have an opportunity like this again in my life? They were so close, right across the street! And there were so many of them!

So, I rolled down the window, started blaring my horn, and hooted and hollered: “Work it!” and “You know how mama likes it!” and “Shake that sexy thing!” Their collective pace slowed, and they looked at me, dumbfounded. It didn’t feel as great as I thought it would.

If you are something when someone is watching, and you are something else when no one is watching, what are you when you are the one watching?

You are powerful, that’s what. Ask yourself: Do I want that power?

Anecdote 3: Sitting on the other side of the table

Currently I am the “directing observer” for a show, “Master Harold”. . . and the boys, which is a politically and racially charged play that takes place in 1950’s South Africa during the height of apartheid. The play has only three characters, two black men in their 40s and 50s, and one white, seventeen year-old boy. Here is the breakdown of the remaining people in the room: my director, a brilliant black man in his 50s; the stage manager and assistant stage manager, both women, white, in their 30s and 20s, respectively; and then there’s me, a white Jewish woman, late 20s.

During rehearsals, I am behind the table. Seated. Watching. This is a foreign place for me to be. I am either an artist-performer, on my feet taking direction, the subject of the director’s gaze; or as the choreographer, I’m in the trenches, in the center of the floor leading the rehearsal, the subject of the company’s gaze. In either scenario I have agreed to the contract, where I am the subject, receiving another’s gaze. And that is where I feel most at home, at least as a performer.

But when I am on the other side, when I am a silent observer, the power that I feel I possess is actually oppressive. The black man who plays the role of Sam is a seasoned and much sought after actor. And he has this habit of frequently “checking in” with me while he’s in character running a scene. It’s both flattering and unnerving. In the early stages, I had to avert my eyes. Now I just grit my teeth as I hold his gaze, trying to stay present. My inner monologue, however, goes like this: “Don’t look at me! A moment ago I was lost in your performance, and now you caught me, and I’m vulnerable! Don’t look to me as the arbiter! You are brilliant, a master! Don’t rely on me and my judgment to inform your performance! Just do your thing! Pretend I’m not here! I just want to watch you and your brilliance without your knowing that I’m watching . . .” Maybe that’s why we need the fourth wall in theatre so that audiences can feel free to observe without being observed.

In terms of gender and race: I am a woman gazing upon three very talented men. And the fact that two of them are older, and black, adds all these additional layers. I actually feel, almost on a subliminal level, these undercurrents that are informed from and are further intensified by the themes in “Master Harold.” It’s a situation I don’t find myself in often, one that I am grateful to have though. The process has been illuminating.

So, returning to the questions at hand:

Can you ever really know yourself? Because as soon as you realize that you are observing yourself, your behavior, inherently, changes. Is there always a part of oneself watching, observing? Can we exist without a witness? If not, is that then the role of G-d? Actress Susan Sarandon, in reference to marriage said: “We need a witness to our lives. There are a billion people on the planet... I mean, what does any one life really mean? But in a marriage . . . you’re saying, 'Your life will not go unnoticed because I will notice it. Your life will not go un-witnessed because I will be your witness'.”

And that’s why, I believe, sharing stories is not just part of the Jewish tradition, it is at the fundamental core of our individual identities. It says, “I am here." (Henani!). I exist. Witness me and my life.

So, can I get a witness?

This post is the second in a series on “Jewesses with Attitude”—Passion, Power, and Pulp Friction.

As someone who tries to live with intention, it's difficult for me to think about not thinking. But the truth is, when we are alone we drop the veil. Often we lose our intentional focus and "just be". And we are different when we're not being watched, when we're not watching ourselves.

This is a fascinating discussion using quantum physics and wave-particle duality to examine what really is a social psychology question. We have seen, time and again, that when people don't feel they're being watched their behavior is different. And the same with us when we are not intentional or mindful of our being. It explains why we can eat an entire bag of chips while watching TV and not even know it - having no recollection of the taste or texture or feeling.

We behave differently in difference environments, just like many particles do. Because the pressure, light, temperature and energy affects us just as it does the tiny parts that are intrinsic in our DNA.