A Visit to the Tucson Jewish History Museum

Last summer, as I sat in an airport, I scrolled past a tweet by Full Frontal with Samantha Bee writer Nicole Silverberg.

as I've gotten older, my vacation persona has expanded from "let's eat every good thing in this cool city" to "let's eat every good thing in this cool city AS SOON AS I've learned everything about where the Jews used to live and what their lives were like and how many died and wh

— Nicole Silverberg (@nsilverberg) June 16, 2018

Usually, I forget tweets as soon as I read them, but this one stuck with me because the sentiment resonated in my gut. A few years ago, I spent a full day in Paris wandering around the Jewish quarter, photographing shop windows boasting tee shirts that said “Don’t worry, be Jewish!” and watching the sun glint off of rifles held by guards outside of synagogues. It was a disquieting experience to exist as both a tourist and insider. I felt a deep connection to the area by virtue of understanding my religious background and cultural ties, and simultaneously understood I was merely peering into the current lives of real people.

I felt the same anxiety a few years later at the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, as I watched a reel tape explain that only 20 percent of the estimated 80,000 Jews living in the city at the outbreak of World War II survived to 1945. Behind me, a mother commented to her daughter that the Secret Annex wasn’t nearly as small as she’d been led to believe. “It’s really quite roomy,” she stage-whispered as we moved in a group toward the gift shop. I closed my eyes and tried not to imagine myself vomiting into a storied Dutch canal.

I almost swore off of visiting Jewish museums and memorials entirely after my experience in the Netherlands. Wandering through an exhibit dedicated to Bergen-Belsen with a Star of David necklace around my neck made me feel naked, like a piece of the display. My partner generally refuses to visit Holocaust-adjacent sites to avoid this feeling of exposure. He knows his family history and carries his cultural inheritance with him daily; that is enough remembrance for him. But even after my disappointments in Europe, I can’t seem to stay away. I keep coming back because I want to commit stories to memory, find moments of joy, and recognize myself in the faces that line the archives.

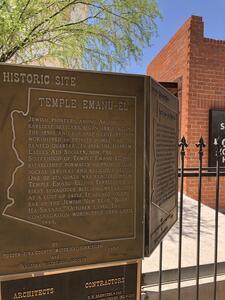

When I moved to Tucson, I didn’t expect the city to have a Jewish History Museum. I noticed the building one afternoon this spring on my way to work, and realized I’d been passing it daily without knowing it was there. The instinct flared immediately: I need to know about where the Jews live and what their lives were like and, and, and...

I finally got my act together and paid a formal visit a few weeks ago, catching the tail end of an exhibit called Meanings Not Yet Imagined. The bulk of the collections are housed in the oldest synagogue structure in the state of Arizona, having functioned as a shul with a congregation from 1910 until the mid-century. In 2007, the space was reclaimed for the purposes of building a community space, featuring a permanent museum and educational center, to reflect and collaborate.

Meanings Not Yet Imagined is an attempt to connect “Jewish experiences in Southern Arizona to local communities past, present, and future” through oral histories, ritual objects, and personal effects. Though there is no set path for visitors to take through the collection, the first brief video clip I watched firmly situated the Jewish community of Tucson (and Tucson more broadly) within the history of the land before settlers arrived. I was impressed by how deliberately Indigenous communities were referenced, incorporated into, and acknowledged in the exhibit.

Similarly, in the adjacent Holocaust education center, exhibits focused on both survivors of the Shoah who eventually settled in Southern Arizona and communities facing persecution today. Andrew Stanbridge’s Call Me Rohingya, a series of portraits of those fleeing violence in Myanmar and currently residing in refugee camps, reminds visitors that “Never Again” requires the internalization of the painful lessons of the Shoah in order to prevent future destruction. It does not cheapen the memory of the Holocaust to remind ourselves that genocide is not confined to Europe in the mid-1900s.

During my visit, I had the opportunity to speak with Ariel Goldberg, the curator of community engagement for the Museum and author of The Estrangement Principle. Goldberg and I had crossed paths a few times before—once at an art gallery opening, and again via mutual work with Protocols Magazine. Post-visit, I emailed them with the questions that sprang to mind as I wandered the galleries. We dove into the history of the space, and the goals of the programs the Museum works to develop.

“By virtue of our campus having two discreet buildings,” Ariel wrote, “one that is the first synagogue founded in Arizona territory in 1910, and then next door a Holocaust History Center that opened in 2016 after being converted from [a family] home...we are simultaneously the oldest and the newest Jewish space in Tucson.” This dual-existence, they further explained, lends itself to one of the guiding principles of the museum’s method for presenting history: “polyvocality.” Ariel describes polyvocality as “antithetical to hierarchical master narratives that are often told from the perspective of the ruling class”—requiring content to be primarily sourced from community members. This aligned with my experience at the museum, and I was heartened to understand the deliberate consideration of overlapping narratives that went into curating a portrait of Jewish life in Southern Arizona.

On the subject of the Holocaust education center, I had written to Ariel specifically about the suffocation I felt in typical exhibits. Ariel responded to my reflection: “There are typically two strains of Holocaust memorialization: to make the Holocaust exceptional, or to make it in conversation with other genocides and epidemics of violence. We see our approach as less about comparison, and instead as holding a messy multiplicity while thinking across history and time.” This “messy multiplicity” is a balancing act, executed beautifully—the survivors are the core of the Center, presented as people who lived (and live) both in and beyond the shadow of the Shoah.

The easiest way to summarize my afternoon at Tucson’s Jewish Museum, on a slow, breezy day in May, is to state what I gained: a sense of belonging. I should know by now that there are few places untouched by Jewish history—that even one Jewish person living and existing in a space means that there is Jewish history to be remembered. Museums are living things, buoyed by the community they exist in and for. To that end, this visit made me put both feet on the ground in Arizona, reminding me that Tucson is a place where I can live and work and have Jewish experiences, because so many others have done so before me.