Neither Egg, Nor Cream: An Afternoon at the Tucson Jewish Film Festival

Before last week, my relationship to the egg cream could have been summarized by a simple story. A few years ago, while at a delicatessen in New Jersey, I ordered an egg cream because I had a vague sense of its status as a firmly Jewish invention. I was sure it was the only proper drink to accompany a pastrami on rye, and expectations were high. I watched the milk and chocolate syrup meld by way of seltzer jetting out from a real old-fashioned bottle, complete with pump. The person preparing my drink stirred frantically and quickly, and the head of bubbles appeared and floated above the chocolate milk underneath. It was quick, simple, and beautiful to watch.

It wasn’t quite so beautiful in taste. I realized a few sips in that the bubbles and chocolate and milk weren’t really working for me. I finished it, dutifully, because I was in Clifton and my pastrami was getting cold and I’d paid $6.50 for the privilege of drinking an egg cream. More than anything, I was embarrassed that I wasn’t in love with a fountain drink I felt I was supposed to love. I didn’t grow up in the Northeast, but my parents did, and even if they didn’t drink egg creams regularly, the option existed on menus at delis they frequented. I had always loved being a North Carolinian, but took pride in knowing every NJ Transit stop between Bloomfield Avenue and Penn Station. I sprinkled Yiddish into everyday conversation. I always polished off every wayward piece of lox that fell off of a bagel schmeared with more cream cheese than should be allowed. I assumed egg creams would delight the taste buds grounded in the deep recesses of my DNA.

All of this is to say: When I saw a flyer advertising the Tucson International Jewish Film Festival at the Jewish Community Center, with something called Egg Cream listed as a short film to be shown toward the end of January, I was intrigued. Years had passed since my ill-fated attempt at a romance with the beverage. Approaching it by way of documentary appealed to the historian in me, and so last Sunday I set off for the Tucson JCC.

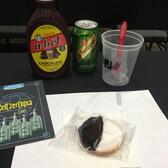

The screening was held in a conference hall within the JCC, with dozens of long tables set up and hundreds of chairs facing the projection screen. At each place setting sat a packaged black and white cookie (“COURTESY OF JOEY’S FINE FOODS: NEWARK, NEW JERSEY”), a container of U-bet’s chocolate syrup, and a plastic cup and spoon. I looked to my left and right for milk or seltzer—no luck. I hadn’t anticipated the possibility of actual egg creams being provided during the screening, and assumed the lack of two key ingredients meant we’d have to wait until after the short film to assemble our drinks. I finished my black and white before the lights dimmed.

Two other shorts preceded Egg Cream—Stitchers: Tapestry of Spirit, which highlighted an international art project in which women across the globe gathered to cross-stitch the entire Torah; and Wendy’s Shabbat, a meditation on the importance of community for elderly Jews. Each touched me deeply. For the artists in Tapestry of Spirit, each word of the Torah stitched by hand represented a new way of living the text. Each line became intimately familiar, reflecting the weight of their efforts. In Wendy’s Shabbat, the filmmaker followed her grandmother, a widowed Jewish woman living in a retirement community in California, to her weekly refuge: a Shabbat dinner held at a nearby Wendy’s. Faith was not the primary motivation for these weekly Sabbath dinners at the fast food joint—rather, it was the promise of togetherness. The act of sharing a space was a greater ritual than saying prayers. Together, these shorts proved to be an ideal primer for Egg Cream as they too told stories about community and tradition.

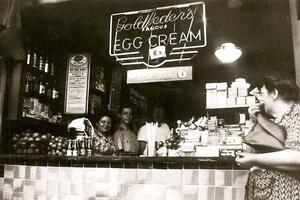

One of the first lines in Egg Cream introduces the great paradox at the heart of this delicatessen classic. “The egg cream,” one of the filmmakers intones over lingering shots of syrup, milk, and seltzer, “contains neither egg nor cream.” So begins a fifteen-minute inside look into the making of a truly American and Jewish beverage—perhaps more ubiquitous than Manischewitz. The film documents the humble beginnings of the drink, born out of necessity and guzzled during sweltering summers in the Lower East Side tenements. A historian points out the bittersweet nature of egg creams as an indulgence of poverty, noting that for Jewish Americans of a certain age and origin, the drink is likely to invoke memories of harder times.

Much like other delicatessen specialties that have undergone a cultural re-fascination and reworking over the last decade, the egg cream has had its share of facelifts. At one point in the documentary, the young daughter of the filmmaker delights in an egg cream topped with real whipped cream and drizzled in fudge, a far cry from the traditional recipe. Sorrow is nowhere to be found.

Endless shots of overflowing egg creams did the trick in making me crave one for the first time since my initial, ill-fated encounter with the drink. By the end of the film, JCC volunteers were coming around to each table with cartons of milk and canned seltzer, warning us not to shake either. I tore into the ingredients eagerly, allowing myself more U-bet syrup than is generally advised and spilling froth on myself in an attempt to whip the milk, seltzer, and syrup into a passable fountain drink.

Was it better than my true-blue deli experience years prior? In taste, I couldn’t discern much difference—though egg cream purists would certainly dispute my assertion. (They still aren’t my beverage choice when eating at a delicatessen.) But there was a sweetness in the participation of building one, amongst dozens of NY transplants, on a Sunday afternoon in Arizona. Enough time had passed since my first egg cream that I missed the idea of them. The same seemed to ring true for the woman to my left—she chuckled to herself as she mixed the seltzer in, confessing that carbonation always bothered her—but didn’t leave a drop behind in her cup.