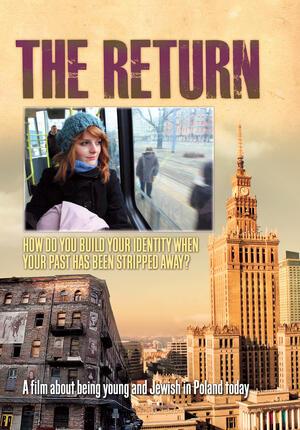

The Return: A Filmmaker Discovers Modern Jewish Poland

How did I end up spending four years traveling across three continents to track the lives of four young Polish women as they explored their newfound Jewish roots?

Because that’s what I do. I’m a documentary filmmaker. I try and get into the lives of people and make sense of their various turns and choices: the stories of how people change over time. It’s a combination of being an anthropologist, journalist and a therapist, all in the service of storytelling. It’s difficult, challenging, maddening—but it’s also the greatest thing in the world.

I'm also Jewish. And those two identities—“filmmaker” and “Jewish”—never had much to do with each other. Over the years I’ve heard of various ideas for Jewish stories to film, but they were usually Holocaust-based or historical—tales that had been told many times before—or they simply didn’t speak to me.

But one day in 2009 I read an article about the interest in Jewish culture in Poland among non-Jewish Poles. Jewish culture festivals were being initiated and curated by non-Jewish Poles, with thousands of Poles exploring klezmer music, learning Yiddish, and other oddities. It lit a fire within me to go to Poland for the first time, to look into this phenomenon and see if there might be a film there.

Still not sure how I’d proceed, I arrived in Poland and went to the Festival of Jewish Culture in Krakow. It was fascinating, and yes, thronged with both Jews and non-Jews. But as interesting as the performers and visitors were, it didn’t “feel like a film;” there was no “story” there to engage me.

But in both Warsaw and Krakow, I discovered something which did fascinate me—a generation of Poles in their 20s, a third generation of Holocaust survivors, who were raised Catholic only to find out in their teens they were actually Jewish. Many of them did in fact embrace that newfound identity, and wanted to figure out what it meant. And since the germ of any good film is people, I sensed there was a story to be told about their experiences and the quest for Jewish identity. I was determined to get to know a cross section of these “new Jews.”

Warsaw and Krakow are two of the largest Jewish communities in Poland. But I soon realized that “largest” is a relative word—in a country which once boasted the highest concentration of Jews in the world, about 3.5 million, there are now perhaps 20,000. So unlike back home in New York, with thousands of Jews in every imaginable category—from secular to reform, conservative, orthodox, ultra orthodox, and every shade in between—Poland has nothing like it. Those two cities have one synagogue and one JCC and it’s actually easy to find and engage with Jewish people there, many of whom are happy to have a drink and talk about their life.

While I came upon many young Jews wrestling with their newfound identity, I was struck by how many leaders in that generation were women. In both communities women were some of the most dynamic, compelling trailblazers, and I was drawn to telling the story of new Polish Jewry through the eyes of women.

How do you “cast” a documentary? You talk to people, hear their stories, get a sense of who they are. Ultimately, I try to find people whom I admire—people who I want to understand, and whose life might take interesting turns.

First there was Tusia, who I met the moment I stepped off the plane in Warsaw’s Chopin Airport. It was, in fact, pre-arranged: knowing I’d need a “guide” and translator I had been referred to her while in New York. She was just going to help me navigate Warsaw, but I soon found her engagement with Judaism and her drive to uncover the city’s long-lost past so compelling that she became one of the film’s “characters.”

I met a number of her friends, but then, before a trip to Krakow, Tusia said she heard interesting things about Kasia, a young Jewish leader in Warsaw. Kasia met me for tea, and was clearly very smart, articulate and deeply thoughtful about her Jewish identity. But she was also very private and guarded, and uncertain about being filmed.

Kasia’s reluctance was in fact a good sign—there’s always a temptation to film people who are extroverted, comfortable talking about themselves—“open books” who are eager to be filmed. But that dynamic wears thin, and someone who is more considered, even reluctant to enter a filming relationship might slowly unfold in fascinating ways. It took numerous meetings over the next year to get Kasia on board, but she turned into a wonderful collaborator with whom I was always eager to catch up—as she moved over time from Krakow to Warsaw to Germany to Israel.

At the JCC in Krakow Maria was a key figure—teacher, administrator, and one of the Center’s principal program directors. She was a fascinating mixture: born into a fiercely secular family, Maria had always known she was Jewish. She was also a single mother who had recently met David, an Orthodox man studying to be a rabbi. Very quickly they decided to get married. That complex backstory barely scratched the surface of who Maria was, and including her in the film was obvious. Her wedding was one of the rare Jewish weddings in Poland, held right in the courtyard of the JCC, and it became one of the first scenes filmed for the documentary. Maria’s ensuing life choices and decisions over the next four years were dizzying, dramatic and fascinating.

The last woman I met was Katka, who in fact wasn’t Jewish at all—she was a “lapsed Catholic” from Slovakia. She started dipping her toes into the Jewish world via her Warsovian boyfriend. My wife and I met her briefly at a Shabbat Havurah dinner, but it wasn’t until the next morning, in the Orthodox synagogue in Warsaw, that Amy and Katka bonded in the women’s section upstairs. After services Amy said “you’ve got to get to know Katka better!” and I did. Katka was a warm, intelligent 21-year-old when we began filming. Over time, it became clear that she would undertake an Orthodox conversion, and that three-year journey became one of the film’s compelling through lines.

I spent four fascinating years filming Katka, Maria, Kasia and Tusia as their Jewish lives developed, changed, and changed again. Now that the film is over and being shown around the world, their lives continue to evolve. Post-screening discussions often focus on their “extended coda.” I’ve also had the joy and privilege of screening the film with each in attendance, wherever they may be living—Brooklyn, Jerusalem, Prague, Warsaw. I’ve come to see that the story I tell is really just a slice of time, a complete film story in itself, but which continues, in the “real” world, to ripple outward. Having been blessed to meet and film four remarkable young women, I’m glad to see their stories are still a work-in-progress.

Adam Zucker’s documentary THE RETURN has screened in over 40 venues in eight different countries. For information about screenings, press, bookings and more, TheReturnDocumentary.com