Imagining the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire

What is about this fire that draws us so intensely? Why has this one event become such a touchstone for political, artistic, and cultural work? How do we explain the nearly one hundred years of memorialization, activism, and creativity inspired by the events which transpired on March 25, 1911 at 29 Washington Place, just east of New York’s stately Washington Square?

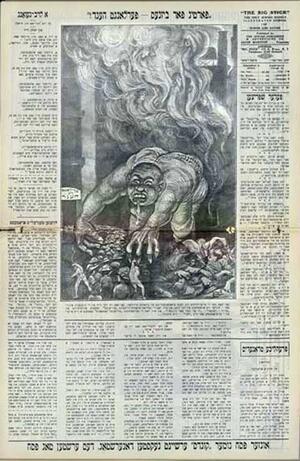

Perhaps the idea that the fire, which still holds the dubious distinction of being the worst industrial accident in American history, consumed the lives of 146 mostly young, single women, who stood on the brink of their adulthoods, helps explain part of the power of its imagery in stimulating novels, plays, movies, works of art, and television dramas. The fact that these young women not only were just starting out, but that they were the daughters of immigrants –and young immigrants themselves—who had come to America primarily from southern Italy and eastern Europe has heightened its power. Here we have a living theater, played out on the streets of industrial New York. Over one hundred young women, Jewish and Italian in the main, had alone or with their families opted for migration as the best way to secure a better life. Yet the fire which ripped through the factory gave lie to their dreams, shattering them just as the gruesome jumps of the girls to their deaths, shattered their bones.

Maybe we, for almost a century now, have been mesmerized by this fire because so many of these same “girls,” or others just like them –their sisters figuratively-- two years earlier had gone out on strike for better conditions and higher wages. These daughters of steerage and of the slums had launched in 1909 the “uprising of the 20,000,” a dramatic labor action which turned the industry upside down and forced unionization on their reluctant employers. And now so many of these militant, energetic, and articulate young women lay dead on the streets and burnt in the workrooms. The contrast could not have been sharper. TheTriangle Shirtwaist fire provided its share of martyrs to the history of the American labor movement.

But the story, like any good one which succeeds in being about more than itself, also pivots on triumph in the face of tragedy. Newspapers of the day provided grim photographs of rows of the bodies draped in shrouds. The press reported how the victims had been trapped in the building behind locked doors with no escape and provided a stark listing of the names and addresses of all those who perished. These all seized the conscience and consciousness of New York and the American public opinion, bringing together the reformers who had long been pressing for factory inspection legislation and other interventions by the state to protect workers from the greed of employers with the politicians who now, in the wake of the fire, came around and decided to support the progressive agenda.

The laws, even if rarely enforced and poorly funded, which came about upon the heels of the fire, has allowed this tragedy to emerge in the historical imagination as both a moment of tragedy and evidence of redemption. These two together surely constitute the stuff which inspires, in its own time and for decades to come.

Hasia Diner is the Paul and Sylvia Steinberg professor of American Jewish History at New York University. Her most recent book, We Remember With Reverence and Love: American Jews and the Myth of Silence After the Holocaust, won the 2010 National Jewish Book Award for American Jewish Studies.