Seeds of Sustenance: Pandemic Victory Gardens

Within an hour, I’d killed the cucumber. The robust, healthy-looking plant—firm stem, heart-shaped, emerald leaves as big as my hand, and half-a-dozen yellow flowers whose anthers burst with pollen—had seemed ripe for replanting. For weeks, I’d cultivated the seedling, moving it from smaller pots to larger ones, and it seemed ready for the raised-bed planter that runs along the rim of my front balcony. I had removed the thick, ugly tangle of weeds that had taken over the planter, and I was equipped with fresh soil, compost, and handfuls of dead leaves to spread over the bed to help it retain moisture. Next to the cucumber, the runner bean and tomato starter plants stood on their own, taking to their new home without issue. But the cucumber drooped and withered in minutes, a time-lapsed video before my eyes. The direct Israeli sunlight, stark and blazing in early June, was too much for it to bear.

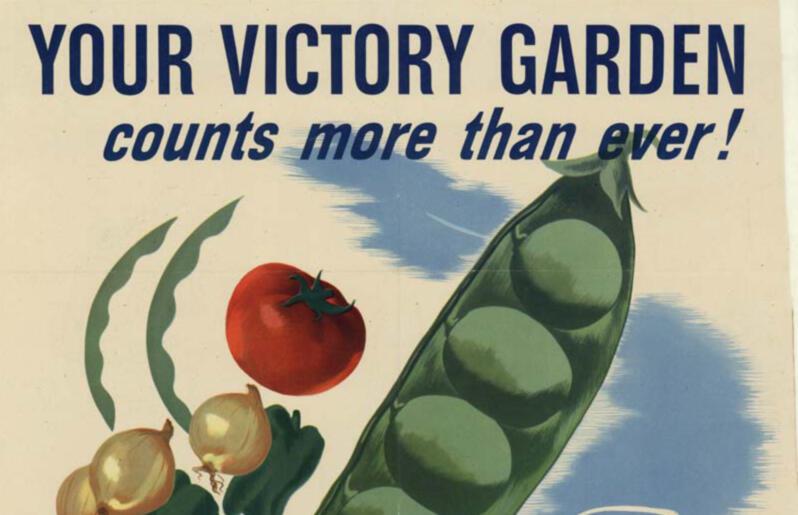

My corona victory garden, as I call it, began in late March. I was not alone in my new hobby; one can find slews of articles in The New York Times, Slate, and others comparing the current gardening fad to wartime victory gardens, when, during both world wars, civilians were encouraged to “grow vitamins at [their] kitchen door.” Government-issued posters portrayed ruddy-faced men, women, and children in overalls clutching hoes and pitchforks, their baskets lush with carrots, tomatoes, and lettuce. “Our food is fighting for us,” the adverts declared. Cultivating a victory garden was an act of patriotism because growing one’s own vegetables meant more industrial-grown produce for the troops.

As a 1943 issue of The Jewish Veteran admonished its readers: “In listening to your radio and reading the papers, you know there may be a shortage in food—UNLESS there is an increase in farm help, and unless many of us raise sufficient vegetables through Victory Gardens… Food will play an important part in winning this war… Remember, you are not yet giving your all—your country is looking to you to help her in this hour of peril.”

During World War II, victory gardens sprung up in backyards, schools, city plots, vacant lots, and public spaces such as Boston’s Emerald Necklace and San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. Eleanor Roosevelt had one planted on the White House lawn. Friendly competitions, local demonstrations, classes, special supplements in newspapers and traveling exhibitions contributed to the efforts. The push was successful: Over 20 million victory gardens were planted in the United States, supplying about 40 percent of domestic demand for fruits and vegetables.

It’s no surprise that so many have turned to gardening in the age of COVID-19; stuck at home, we search for activities to boost morale, ideally something healthier than baking binges and cocktail crazes. Working with my little starter plants, sprinkling seeds from store-bought tomatoes into a patch of soil to see them sprout a few days later, reading up on hand-pollinating my zucchini flowers—these are small, tangible things that give me a tiny sense of control when so much else is unknown. The gratification is well worth the soil underneath my fingernails, and I trust that patriotism and economic pragmatism weren’t the only reason wartime victory gardens were popular.

I set out to learn if there was anything particularly feminist, or Jewish, about wartime victory gardens. I found a few instances of Jewish organizations (Pioneer Women, for one) encouraging their members to grow victory gardens, but these do not seem distinct from the general activities aimed at helping the war effort: buying bonds, participating in blood drives, volunteering for the Red Cross, organizing care packages and so on.

Likewise, I found academic works exploring questions of whether planting victory gardens helped transform women’s roles. It’s not difficult to infuse meaning after the fact. Certainly, the Women’s Land Armies—government-established programs to supplement the male labor shortage on farms—made contributions in transforming women’s rights. During and after World War I, for example, female “farmerettes” were successful in achieving equal pay for equal work and helped boost the suffrage movement. According to a 1918 edition of the American Jewish Chronicle, there was at least one Jewish unit of the Women’s Land Army.

* * *

Here in Israel, we went into lockdown rapidly. On March 12, 2020, I was still taking the train to my office in Tel Aviv, and the kids were in school. Within days, not only had schools and many workplaces closed, but synagogues were shuttered and gatherings were limited to ten people. By March 25, non-essential workers could only go outside for brief trips to stock up on food or medical supplies or for “short walks of no more than 100 meters from one’s home.” The measures had me thinking in terms of circles and radii: We’d gone from living and interacting freely within the entire country to being ringed in within our towns and cities, and then further encircled within our neighborhoods, and then our households. I became more attentive to the natural beauty in my 100 meter radius: multicolored rosebushes in front of a nearby apartment, the Judas tree with edible flowers in my yard, the way the sunbirds and spectacled bulbuls always show up in pairs.

COVID-19 has forced us to reinvent many aspects of our lives, a further “circling in” on ourselves. For many, this means finding new ways to make a living. For others, it means figuring out which activities help us get through the long, isolating days. My eleven-year-old, who’d never been good at occupying herself, discovered Legos and zipped through the last three Harry Potter books. My coping methods include things I’ve always done—spending time outdoors, reading, attempting to write—but also new activities: journaling, joining a weekly birdwatching Zoom call, delivering food packages, and puttering around in my victory garden.

In “our hour of peril,” the radii extend outward, too. Examples abound of people banding together to help the elderly, support the unemployed, cheer on medical and other essential workers. And there are victory gardens being cultivated for social good, such as those planted by the members of Congregation Etz Chaim in Lombard, IL and Hazon to help bolster local food pantries.

Like the victory gardeners of yore, the garden is more work than I anticipated, and not everything works. On some mornings, I spend an hour and a half or more moving starter plants to bigger pots, mixing soil with compost, searching for string to prop up the tomatoes. I experiment. Yesterday I pulled out the runner bean, which had grown massive but so full of aphids that it threatened the neighboring plants. A few hours after I thought I’d killed the cucumber, I performed “emergency surgery,” moving it back to its original pot in the shade. Happily, after a few days, it came back to life, and as I write, it is full of lovely yellow flowers and six sprouting cucumbers. After initial success in managing the virus, we’re in a full-blown second wave here in Israel; I visit my cucumbers and tomatoes several times a day because they shore me up.

When future historians study our current moment, it’s hard to guess which seeds of change they’ll find in our COVID-era gardens. I suspect there will be many, like me, pointing to our gardens as something that provided both physical and mental sustenance. And on a larger scale, I hope they’ll find that victory gardens are one step toward—in the words of Hazon—“A society-wide commitment to living lighter on this planet, to living in more right relationship with each other and the Earth.”

Beautiful Julie - the initiative itself, the experience you share with us, your connecting this endeavour of yours up with others', the way you convey your enthusiasm and wonder that you can actually grow things to eat. Love it!

Great writing. Didn't know about the victory gardens so a little history lesson thrown in was great. It makes me feel good that I have had a plot of land for the last 20 years where I grow my own organic veg and fruit. Keep writing.

Lovely piece. Thanks.

I had a similar story - but most of my plants perished, or were eaten by snails! Cherish your cukes!

I love this essay, and I hope you’re harvesting cucumbers.