Not Just Potatoes: Legacies of Yiddish Vegetarianism

The beginning of the twentieth century was, for many, a time of hope for a better world. Technology was improving at a never-before-seen rate, and in many parts of the diaspora, Jews were finally being allowed into mainstream society. Some Jews began to hope they could become instrumental participants in building that better world—and many were forming movements in order to do so through action. These movements took many shapes: Bundism, socialism, early forms of Zionism, Jewish anarchism like that championed by Emma Goldman, and so on.

One way in which members of the early twentieth-century Jewish diaspora worked toward building the world they wanted to see was through their food. If one were to explore the archives of Jewish publications from the 1920s and 1930s, they would find copious material on a surprising topic: vegetarianism. Though they are little-known today, dozens of Jewish journals and cookbooks on vegetarian topics were produced in Yiddish-speaking parts of the diaspora during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These publications were deeply idealist, with titles such as Thou Shalt Not Kill, The Naturist (and Vegetarian), and Health and Life. They were suffused with the ethic of personal choice as a way to build a better world, sometimes to a borderline-religious degree: The first issue of The Vegetarian World contains a hymn to vegetarianism.

Professor Eve Jochnowitz at the University of Michigan is the premier scholar of Ashkenazi food history. In her scholarly work, Jochnowitz has chronicled Yiddish vegetarianism as a political movement. She is also the translator of Fania Lewando’s The Vilna Vegetarian Cookbook.

According to Jochnowitz, the Yiddish vegetarians were fundamentally utopian thinkers. During the early twentieth century, she says, “Jews, and really everyone, were sensing that it is possible that the future can be a much better time and that people can play a role in making the future better.” Jochnowitz notes that although this was a very Jewish way of thinking, it was not only Jews who saw the first half of the 1900s as a period of hope; the 1939 New York World's Fair was themed “building the world of tomorrow.” However, “building the world of tomorrow” through food was a more popular approach among Jews than among other groups—possibly because of the long legacy of Jewish thinking about food as a moral topic.

“I think vegetarianism caught on a little more among Jews than in these other groups, and it may have something to do with kashrus, the Jewish dietary laws,” Jochnowitz explains. “Jews already have this built-in understanding that what we eat is part of how we shape the world.”

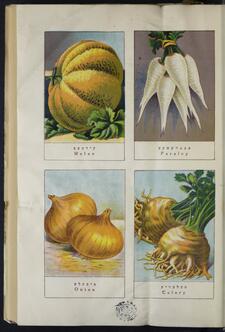

For Jochnowitz, who practices a vegetarian diet herself, reviving this part of Jewish history is a passion project. However, it is not without its challenges—translating Yiddish writing about food presents its own particular set of issues, such as confusion surrounding what the Yiddish names of foods actually mean in English. “Terminology for food items is so local,” Jochnowitz points out. “In one region, a pumpkin’s called a dinye, and in another it’s a banye, and in another it’s a dinke, and in another it’s a kabak. I have about seven or eight words for pumpkin. In Yiddish, English pepper is often the direct translation of the word for allspice, which is neither English nor pepper. So you need to have a pretty big culinary vocabulary under your belt.”

As Jochnowitz puts it, “It’s not all ‘zuntik bulbes, montik bulbes, dinstik bulbes,’” quoting a popular Yiddish song about eating potatoes every single day for every single meal. “Yes, that is vegetarian, but it’s not really a thrilling diet. What I see from these cookbooks and from these journals is that Jews were eating, when they had the opportunity, a whole lot of really interesting vegetable dishes. Mango, tapioca... these interesting root vegetables. The foods and foodways of Ashkenazi culture are much more multi-layered and multi-textured than popular culture generally imagines them to be.”

The Yiddish vegetarians can teach us that the Jewish inheritance of food is much richer than just potato latkes and brisket. They can also show us that a century ago, unusual dietary choices received as much pushback as they do now.

“On the negative side, we can learn from the reaction [twentieth century Yiddish vegetarians received],” Jochnowitz says. “In that century, as in our own, anyone that strays outside the hegemonic, industrial omnivory is greeted with acid opprobrium and biting satire. Though at least the satire from the twentieth century was funny. It’s really considered a threat when people try to eat adventurously.” Food is personal, but it is also political, as today’s intense dialogues over what is morally correct to eat attest.

Most importantly, though, these cookbooks and Jochnowitz’s research offer a glimpse of another aspect of our collective culinary and activist history—and the way those intersect to create pickle-potato soup, long essays on the Talmudic virtuousness of vegetarianism, and vegetarian brisket. Today, as many of us are thinking more critically about both the ethics of what we eat and Jewish activist legacies, the Yiddish vegetarians seem like a more relevant part of our history than ever—and they had some good recipes, too.

Thank you for this! I'd love to read more of Professor Jochnowitz' work chronicling Yiddish vegetarianism as a political movement. Any pointers, gratefully received. !א דאנק

Glad to see Eve’s good work recognized.❤️

My grandfather came from Volkovisk, Russia/Poland in 1904. He settled in Brooklyn, NY. He was a "moral vegetarian" and stayed that way until he passed away at 89. He even had a water pump put in his brooklyn backyard. Many in my family were also vegetarians. I also remember working one summer at Fannie Shaffer's Vegetarian Hotel in the Catskills in the 1960's. It was a wonderful hotel with mostly Jewish guests and the food was great.

In reply to My grandfather came from… by Janice Caban

Janice Caban,

I would love to talk with you about this.