A Young Feminist's Siddur

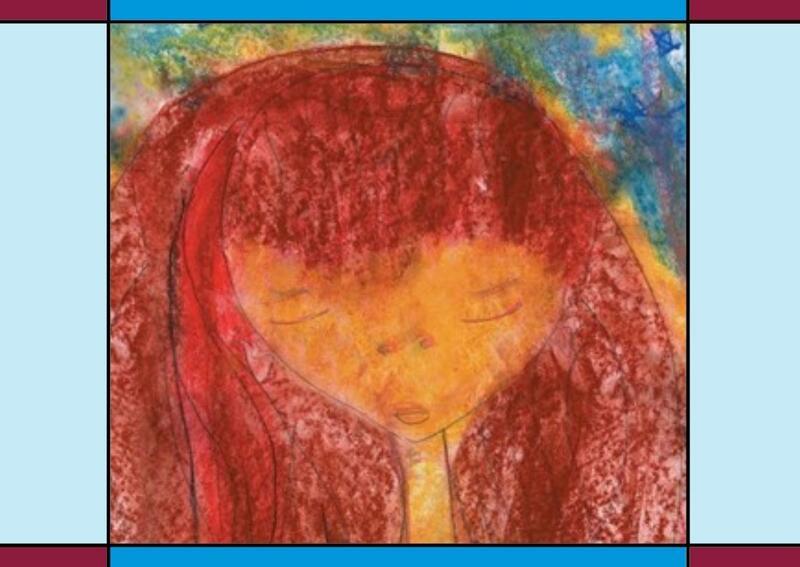

When I stared down at my siddur for the first time, the one I would come to memorize, I ran my pudgy fingers over the fiery red woman featured on its glossy cover. I thought she looked a bit like an alien. With her eyes closed, she appeared all-knowing and at peace—two qualities that weren’t exactly relatable for my hyper kindergarten self. I wondered if this woman was supposed to represent the all-powerful God my parents talked about. Glancing further down on the cover, I read the title: With All Your Heart. Although I didn’t know it then, that simple siddur title would come to describe my personal relationship with Judaism as a young feminist.

When I first obtained the siddur all those years ago in kindergarten, my school assigned our parents the task of making each child's book unique. In the first few pages of With All Your Heart, my parents drew detailed sketches of my childhood home, our cobblestone walkway and lemon tree included. This drawing, however, was no ordinary sketch: words line every wall and roof peak. "Frozen yogurt,” “Harry Potter,” and “rollerblading” surround my window, and “gymnastics,” “Coronado,” and “coloring” pave the driveway. Looking back on these sketches now, my heart aches for the simple happiness of my childhood. Yet, I’m also affirmed by the ways in which my current identity is much more multifaceted than it was in my time at my Jewish day school.

During much of my time at my Jewish day school in Arizona, I didn’t understand the significance of prayer. Every morning, I quietly mumbled the Hebrew words, mimicking the older kids. Much to my surprise, in first grade the words actually started to take shape in my throat. Despite my literacy, the significance of these prayers was still archaic and distant. Were these prayers not thousands of years old, and thus irrelevant to my day-to-day life? I took Hebrew and Jewish Studies courses throughout elementary school, but my feelings on spirituality never mirrored my growing Jewish historical and textual knowledge. Focusing on pure faith wasn’t nearly as captivating as the beautiful tunes we sang in services or the colorful texts and graphics in my siddur. Nonetheless, I sang Modeh Ani and Mah Tovu loud (and perhaps with a bit too much pride). I was determined to be the kid with a voice like Adele and with superior pronunciation to the rest of my peers. I took care in scrutinizing the Hebrew accents during the silence of the Amidah and pinning down the flow of the complicated words of the Ashrei.

I worked hard to be spiritual, and during those years of my life, it was enough. My Judaica teachers spoke of God with passion, but to me, God never really felt present. What did They do that affected the way I experienced life? In my fourth-grade, Percy Jackson-obsessed mind, God played the same role that Poseidon did: A figure that was fun to read about despite my acceptance that my fascination was strictly mythological. I didn’t feel connected to Judaism in the way I was told to by my teachers, but those mornings spent with the woman on the cover of my siddur encouraged me to stand my ground in the sanctuary, outfitted in my pink sparkly Justice dress and all. During these moments, I gazed at the fiery woman on the cover of my siddur and determined that I also wanted to be an unapologetically powerful (albeit non-alien) woman.

As my safta would say, I developed “ruach” and carried this tenacity with me throughout middle school, even as I distanced myself from prayers and the physical siddur. Instead, I committed myself to synchronized swimming, writing, and theater. I gave my heart to those endeavors just as the title of the siddur had urged me. As a junior in high school, I still strive to emulate that same energy in my pursuits. This learned ruach also connects me to a long line of feminist predecessors: Esther, Julie Rosewald, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Betty Freidan, to name a few. I believe that these women’s practices of feminism stemmed from their cultural (not just spiritual) relationship with Jewish traditions, such as tzedakah, techinot, and mitzvot. I’d like to say that my zesty feminist identity comes from those same Jewish traditions, which were first represented by the title and illustrated woman on the cover of my siddur.

Since kindergarten, I’ve moved houses and many of the penciled phrases are no longer personally relevant. In this way, just as my perception of the title, With All Your Heart has changed, so has my self-imposed narrative. I no longer use that saying ("With All Your Heart") as motivation towards being the loudest during morning services; rather, it's the mantra that plays in my mind while rowing thousands of meters during workouts. Similarly, my relationship with Judaism has shifted from attention on God and prayer to the ways in which the Jewish values of kindness and positivity affect my relationships and decision-making. I no longer rely on authority figures to decide my path for me.

I may be a different Elle than I was ten years ago, but she still travels with me as I continue to develop as a woman and a Jew. As human beings, we’re all culminations of our past and present selves; no part of our existence stands alone. We as Jews uniquely choose to embrace that conversation of complexity. I may have never believed in a God, but I’ve still learned the values of feminism and tradition from my connections with prayer and the title and illustrations of my first siddur. And that journey is a beautiful thing. I continue to carry those meaningful parts of my siddur with me, and I leave behind the less relevant parts. This track is growth, power, and a way to mindfully, wholly love both myself and my religion—truly “with all of my heart.” I now close my eyes at night (like my siddur alien) and am finally at peace with who I am: a forever developing woman with an inner Jewish fire set ablaze.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.