Tracing the Roots of Jewish Women's Education

On January 5th, 2020, almost 4,000 people gathered in Jerusalem to celebrate the first-ever women’s Siyum HaShas, marking the conclusion of the Daf Yomi cycle. Daf Yomi participants learn a full page of Talmud every day, with the goal of ultimately learning all six orders of Talmud in seven and a half years. Since Daf Yomi was first established in Lublin, Poland in 1923, men have been the primary participants in this impressive endeavor. This year, at the main Siyum HaShas, which took place at MetLife Stadium in New Jersey, there were over 90,000 attendees. Only 10,000 of them were women. Every speaker was a man, and speakers thanked women for supporting their husbands’ learning (not for participating themselves). In contrast to this male-focused event, the women’s Siyum HaShas centered women’s participation. This event was an enormous leap forward for gender equality in Torah learning, and it wouldn’t have been possible without the revolutionary work of one woman: Sarah Schenirer.

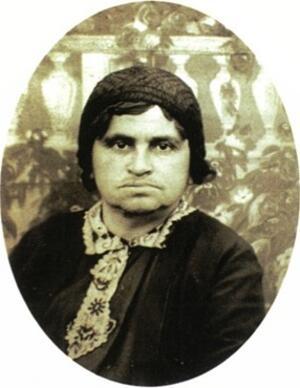

Sarah Schenirer was born in Krakow, Poland in 1883. As a child, Schenirer wished she could learn Torah like her brothers. Her father, a prominent Orthodox rabbi in their community, provided her with religious texts so that she could learn too. Despite her father’s support, Schenirer was still confined to learning alone, at home. Growing up, she watched her friends assimilate into the Polish school system and become passionate about the secular topics that they studied there. But there was no established system within the world of Jewish education to teach girls who sought to explore their Judaism academically.

Schenirer’s family fled to Vienna during World War I. In Vienna, Schenirer was inspired by sermons given by Rabbi Dr. Moshe Flesch highlighting the important roles women have held throughout Jewish history. Upon her return to Krakow in 1917, Schenirer immediately set out to expand the opportunities for women to learn Torah and engage with their Judaism. She aspired to create a school to formally educate young women, and sought to do so through her founding of the Bais Yaakov movement. She opened a school with 25 elementary school-age students; within just a few months, it had expanded to 40 students. The movement continued to grow, opening more schools and providing more girls with a formal Jewish education. Whereas Jewish girls had previously been confined to only learn about Jewish tradition from their family, Schenirer successfully established a movement to make formal Jewish education accessible to girls. Today, Bais Yaakov schools teach Torah to thousands of young women.

Though I also learn Torah in my school, the type of Torah taught in Bais Yaakov schools differs greatly from what I learn at my Modern Orthodox day school. The Bais Yaakov curriculum distinguishes between study of the written Torah, Tanach, which it permits and encourages, and study of the Oral Torah, Talmud, which it forbids. This distinction was fundamental to Schenirer’s success in gaining rabbinic approval for her educational mission. According to many Orthodox rabbis during Schenirer’s time, women should be forbidden from learning Talmud because of an idea expressed by Rabbi Eliezer in the Talmud: “Anyone who teaches his daughter Torah teaches her tiflut (licentiousness, triviality).” The Bais Yaakov movement, and Orthodox rabbis during Schenirer’s time, interpreted this idea to only apply to Oral Torah, and not written Torah. In contrast, at my Modern Orthodox day school, I learn both Talmud and Tanach every day, in co-ed classes.

Yet, even though I attend a Modern Orthodox day school and not a Bais Yaakov school, I still benefit from Schenirer’s efforts every single day. By normalizing girls’ Torah education, Schenirer laid a strong foundation for later feminist activists to build upon. I learn Talmud and Tanach every day in school because Sarah Schenirer successfully highlighted how critical girls’ Torah education is.

It is also thanks to Sarah Schenirer that the women’s Siyum HaShas was able to take place in January. Just as Schenirer paved a path for women to delve into the depths and intricacies of Tanach, modern Orthodox feminist activists fought to make Talmud learning mainstream for women. One part of the women’s Siyum HaShas was a global Siyum. The six orders of Talmud were split up between cities around the world, and women around the world came together to learn the entire Talmud through. As I learned part of Tractate Rosh Hashanah, the section assigned to Boston this winter, I found myself thinking of the Talmud-learning women who came before me. None of them had been part of a global effort to learn the entire Talmud in anticipation of a momentous Siyum. Instead, they had been on the sidelines, maybe learning in small groups (and that’s if they were fortunate enough to be women learning Talmud at all). Sarah Schenirer started the revolution—that is still in process today—to create equal Torah learning opportunities for women. Significant progress has been made since Schenirer founded the Bais Yaakov movement in 1917, but there is still space to learn from her successful grassroots tactics as we continue the fight.

Sarah Schenirer doesn’t fit the image that people might have for a feminist activist; she lived in a relatively isolated Orthodox Jewish community, and, for the most part, worked within the system, obtaining rabbinic consent before moving forward. Yet, Schenirer’s work serves as a great example for the widespread effect that small-scale, grassroots activism can have. Despite the Bais Yaakov movement’s rapid growth, Schenirer still faced considerable resistance. Schenirer fought for what she believed in, defying social norms and pioneering a groundbreaking educational system. In doing so, Shenirer not only created unprecedented educational opportunities for Orthodox women, she also inspired a group of educated, empowered, and committed Jewish leaders to serve generations to come. Schenirer stood up and dared to claim that Torah is universal, and that all Jews have the right to learn it. She found an ideal balance between tradition and innovation, and used her voice to catalyze progress while, at the same time, meeting her change-averse community’s needs.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.