The Oxymoron of Jewish Feminism

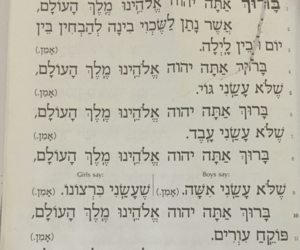

Before I understood what it meant, the Jewish blessing Shelo Asani Isha was just another monotonous phrase I heard every morning at school. In first grade I learned that the word ‘Isha’ means woman, so I thought it was a prayer boys said in the hope that god would find them a wife (heteronormative I know, but that wasn’t part of my vocabulary yet). By third grade, my Hebrew had progressed enough for me scrape together the true meaning of the phrase: “Blessed are you God who did not make me a woman.” I was shocked. I had fallen so deeply in love with Jewish text study that I neglected to see the many ways in which I was not represented in those texts. The tension became clear: How could I honor a tradition that did not make space for me as a female?

When I expressed these feelings to my mother, I was conflicted. On the one hand I wanted to know why people thanked god for not being a girl, a sentiment that seemed so demeaning and offensive. On the other hand I felt protective of these ancient texts. At nine years old, with only the emotional sophistication of a third grader, this direct tension essentially amounted to a temper tantrum. At the time, I had virtually no understanding of feminism, but my parents had started slipping feminist ideals into my life without my noticing. Perhaps that’s why I was enraged. I was slowly discovering that while the idea of gender equality was already second nature to me, that’s not how the world around me operated.

As I slowly began recognizing that gender equality was not inherent outside the walls of my house, more and more things began to deeply anger me. I would come home from school each day with a new and infuriating finding. Maybe I realized that the Torah uses the biologically impossible verb vayeled (he birthed), or maybe I noticed that we only mentioned the names of the Jewish patriarchs and not the matriarchs in our daily prayers. I didn’t have to look hard to find that this was a tradition that idealized men over women. It was when I was in sixth grade that I looked to feminism. Listening to leaders of the modern Feminist movement voice their frustrations made my anger feel justifiable. I realized that I had been living in a bubble where girls sat quietly and pretended they didn’t understand what was being said about them by their own religion. I wasn’t going to live in that bubble anymore.

Soon enough, my shelf was lined with books containing the therapeutic fury of established women writers and activists. I felt so empowered reading these books, but there was a problem. How could I fully buy into the feminist movement and also continue to function within my traditional Jewish community? Segregating these two identities felt impossible, and even hypocritical. I was caught between two worlds that were both so important to me. I loved learning Talmud as much as I loved ranting about its content.

To many, the answer would have been simple—look at the texts from a less Orthodox and literal standpoint; draw from the wealth of Reform and Reconstructionist translations and understandings. For me however, this was challenging. My Jewish education had clearly stated that the text, in its most literal sense, is the law, and that the law isn’t meant to be broken.

To this day I am very much a rule-follower, so although at home I was given explicit permission and even encouragement to look at the texts from a less Orthodox perspective, I felt that I was breaking the boundaries that had stood so rigidly in place since I was three years old. I ultimately made the decision to practice Judaism while adhering both to halacha (Jewish law), and feminist values. In practice, this looks like me wearing tefilin and a tallit, and essentially following all Jewish laws that traditionally apply just to boys, though some days it is difficult to participate in Jewish tradition at all.

Today, my balancing of feminism and Judaism is still difficult, and at times it feels impractical. There are days when I defend my right to wear tefilin and a tallit, and others when I ponder whether it’s worth trying to change Judaism’s ancient traditions by injecting my feminist values. But recently I’ve realized that these dissonances are almost more valuable than either identity on its own. These questions, more than anything else, are the ties that hold my Jewish and feminist identities together. Can these two diametrically opposed identities coexist? As long as I continue to ask these questions, they invariably will.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.