Reflecting on Ester and Ruzya

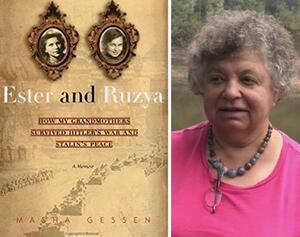

Our March Book Club pick is Masha Gessen’s Ester and Ruzya: How my Grandmothers Survived Hitler’s War and Stalin’s Peace, a family history chronicling Gessen’s grandmothers’ experiences during World War II and the post-war Soviet anti-Semitism in the 1940s and 1950s. Ester and Ruzya, her maternal and paternal grandmothers, respectively, became best friends when they met in Moscow after the war, and spent the rest of the twentieth century side-by-side. Their children ultimately fell in love, married, had Masha and her brother, and emigrated to America. The book is a story of friendship, war, loss of family and homeland, and compromise in the face of authoritarianism.

When Marina Adelsky, a Russian immigrant and JWA family member (her daughter-in-law is our development director, Dina Adelsky), read this book, she had one word to describe it: familiar. Adelsky, who was born in St. Petersburg in 1948, emigrated to America in the 1970s, and now lives in New York, says that Gessen’s family story is in many ways a common tale for Soviet Jews. I talked to Adelsky about how this book shines a light on her own family history and experience as a Soviet Jew in the second half of the 20th century.

First off, what is your own family’s story?

My parents and grandparents all lived in Russia, in what became the Soviet Union. They never actually lived in Poland. The story of Ester, which starts in Bialystok [one of Gessen’s grandmothers was a Polish Jew who fortuitously left for university in Moscow near the beginning of World War II], and her participation in the Bund, is new to me. Nobody in my family did that, although of course I knew it existed.

But the story of the other girl, Ruzya, who grew up in Moscow, is as typical as they come. [Ruzya’s family moved to Moscow in the 1920s, and she was able to enter university despite her Jewish background, in the early, ostensibly more egalitarian days of the Soviet Union.] Everybody went through the same experience. My father was never interested in Communist ideas, but he certainly felt liberated by the fact that he was allowed to live in a big city as a Jew, that he was allowed to apply to the university and to enter the university. At that time, while my family was very much aware of the fact that they were Jewish, there was also a certain equality that they experienced. This is what I think attracted them to being in the Soviet Union. The fact that although they are Jewish, on the surface, they are equal to everybody else. And that’s how it was.

By the way, this was not so for the generation I belong to. We knew we were not on equal footing with Russians. We grew up in Russia, but I knew that as a Jew, I had to be better than 97.5 percent of my class to enter the university.

World War II was a horrifically transformative time period for every character in Ester and Ruzya. Was it the same for your family?

Oh, yes, both sides of my family were impacted by the war. My grandfather on my mother’s side lived through the siege of Leningrad. My grandfather on my father’s side perished, though my father survived. My uncles fought in the war; one perished and one survived.

Towards the end of Ester and Ruzya, the titular characters’ children decide to emigrate to the United States, leaving everything they’ve known behind. Tell us about your experience as an emigré.

We emigrated in 1978. There was a big wave of emigration after us. All our friends emigrated in 1980 and 1981. And then it stopped completely, and started again in the late 1980s.

It was a very hard decision for me personally. It was very hard, primarily because of my family, because I was very close to my parents and my brother, and at the time when we were living, the feeling was you would never see them again. Nobody from Russia was allowed to visit America, and nobody from America was allowed to come visit Russia.

In about 1985 or 1986, I was missing my family terribly. At the time I hadn’t seen them for eight years or so. There was a rumor you could buy a cruise ticket from Sweden to Russia for three days. Because it’s such a short trip, there was an express visa given, and they didn’t scrutinize that you were from Russia. My husband and I flew to Sweden, but we decided it was too risky for both of us to get on that boat. If we were detained in Russia, what would happen to our children? We decided we would go one at a time.

I applied for this boat trip, which was supposed to depart the day after we arrived. The tourist agency was plenty happy to take my money. The next day, there were a bunch of passports on one side of the table, and there was exactly one on the other side of the table, and it was mine. I wasn’t granted a visa. The whole family, my parents, had gathered in St. Petersburg hoping they would finally see me after eight years, but I had to call and tell them no, we’re not coming.

You couldn’t imagine at the time that things would change, but they did.

One of the main themes of Gessen's book is whether, and how much, citizens should compromise their own ideals when living under extreme circumstances or under an oppressive government. Is that something you experienced?

Of course. In Russia, I worked at a research center, doing data processing, and if you worked, you were required to comment on or condemn people who were against the regime. You were supposed to attend a meeting [to condemn people]. And this was a very tough choice. So what do you do if you are asked to condemn someone? It’s very very hard. Some people tried to get a medical excuse [to get out of the meeting], like I did, and some were pretty brave and just said no, I’m not going to do it. And some made it through, but otherse did lose their jobs. And the medical excuse, it had to be from a doctor who you knew.

My father taught at a St. Petersburg branch of the Moscow Institute. He lived at the same time as Masha Gessen’s grandmother, and he was asked to denounce professors. He was the one watching the door and waiting for the bell to ring in the middle of the night, as so many people did in Russia.

Another major theme in Gessen’s book is the importance of close female relationships, especially in a country where so many of the men died in the war. Ester and Ruzya meet when they’re in their twenties, and eventually become as close as family. Was this common? Did you have friendships like this?

This was definitely common in my parents’ generation. It was also common in my generation, and maybe even in the generation of my children. The world is so hostile to you, that your friends are your support, your defense, all your life is in this small group of friends. It cannot be very large, it can be two, or three, or five, but not a large group of people, because you couldn’t trust so many people. You could only trust a few. These people were closer to you than your own family. They were family for practical purposes.

I had a group like that; I met some of them in high school. Guess how fortunate I am? They’re still my friends. They’re in America now.

Ester and Ruzya: How my Grandmothers Survived Hitler’s War and Stalin’s Peace is a JWA Book Club pick; see our Discussion Questions for the book.

Good job JWA!

Thank you for sharing this reflection from "one of our own", Dina's mother-in-law. Knowing the players personally always brings the history closer.