Q & A with Susan Chevlowe, curator of "Missing Generations: Photographs by Jill Freedman"

A new exhibition of photographs by Jill Freedman called Missing Generations is now on view at the Derfner Judaica Museum in Riverdale, NY. The exhibition marks 80 years since the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. It has been 30 years since Freedman traveled to Poland on the fiftieth anniversary to document sites of destruction and the resurgence of Jewish life after the Holocaust in Hungary, Poland and Czechoslovakia. Not previously exhibited, the 36 black-and-white images in Missing Generations capture the milestone events that took place, beginning with commemorations of the Uprising in 1993, which included the return of many survivors for observances in Warsaw and at Auschwitz. Jill Freedman died in 2019 at the age of 79.

JWA spoke with Susan Chevlowe, director and chief curator of the Derfner Judaica Museum, about the exhibition.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

JWA: How did the idea come about for Jill Freedman to take this series of photos in the first place?

Susan: April 1993 was the fiftieth anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. And she just said, I have to be there. She kind of thought of herself as a pilgrim and as a witness. She felt that there was Holocaust denial. She was reading all of this material and hearing that in polls, you know, a large percentage of Americans had never heard of the Holocaust, and some people thought that it was made up.

But also, photography of the Holocaust had really shaped her as a photojournalist from a very young age. When she was a very young girl—she's born in 1939, so after the war when she was a very young girl, I think maybe seven years old—she finds, in her parents' attic, Life magazines from the immediate postwar period that covered the liberation of the camps. And there were many photographs not only of, you know, emaciated survivors, but also of corpses of the dead. And she said that she was really obsessed with what had happened, for many reasons: the pain and suffering of people, the fact that she felt no one intervened to stop what was happening. And she believed passionately that photography could change the world. You know, she believed that her camera was a weapon in the fight for social justice, and she saw the Holocaust within this same fight for social justice that had been happening during her own life. So she just picked up her camera and she said, I have to go.

JWA: One of the things that's striking in this series of photos is that they document not only the destruction of Jewish life in parts of Europe, but also its resurgence. Can you give some examples?

Susan: Yeah, a couple of things. I mean, obviously there were large, Jewish communal institutions working to rebuild Jewish life in Europe after the war. And then there were also big funders. But it took people on the ground, who took it upon themselves to rebuild Jewish life and also to preserve what was left. And, you know, to teach people who had no knowledge of Jewish observance, or people who had knowledge of Jewish observance and no space to keep it because it had been decimated.

[Jill] spent a lot of time with Rabbi Sidon in Prague. He was the only rabbi in the Czech Republic at the time, when she was there. And Rabbi Sidon was running Jewish social services, communal social services. They were having Jewish burials, they were having synagogue observance. And there was a Jewish summer camp in Hungary, and young Jewish people came from different parts of Eastern Europe and he taught Torah there.

JWA: Can you say a bit about why she focused on the resurgence, why that was important?

Susan: She originally went for these commemorative events at these places that were, you know, haunted and empty. Photographers have gone to those sites and photographed them haunted and empty. But people were so important to her. So I think as she met them and heard their stories, it was clear that there was a resurgence, and people were telling her about what was going on. And I think as she learned about it, that's what she became very interested in.

JWA: Can you say a little bit about how the 36 photographs in the exhibition were chosen?

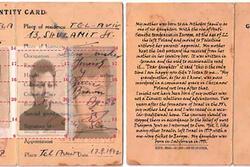

Susan: First of all, 36 is a significant number. So that was meaningful to me. They're meant to be representative of this narrative that unfolds in her book, Missing Generations. It begins at the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial. So we have a couple of photos that she took right at the beginning in 1993 during the commemoration ceremony, where the plaza was filled with survivors, and her photos really focus on them. She was so taken with the fact that after 50 years, people were still looking for their relatives. People even had big signs that said, Do you recognize me? It makes me cry.

So we begin there, where she began, and then on her journey, she visits the cemetery, and she meets people in the cemetery. She met the brother of a Warsaw ghetto fighter, someone who died in the resistance. His skeleton was found later in the ghetto with his girlfriend, and another couple, a husband and wife. They were all buried together in the cemetery in Warsaw. And there's a stone commemorating them.

She visits Majdanek and Treblinka. She sees young people visiting the monuments and families of survivors. She also meets Roman Ferber, the youngest Schindler Jew, at Auschwitz- Birkenau. And she has three photos of him. So that becomes like a little story within the story, of his return to Auschwitz and climbing into his platform in the barracks.

So I wanted to represent these different sections, really, with what stood out as the best photographs, but also to represent different protagonists in her story and important parts of the story.

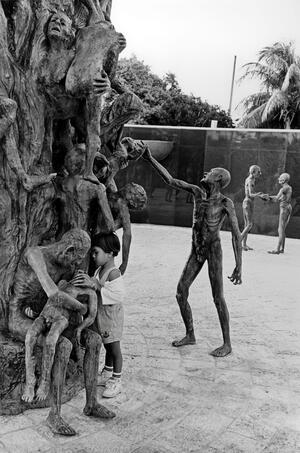

What's also important is, she lived in Miami for about a decade, beginning in the early 1990s, and so she was around a lot of the survivor community in Miami Beach. And then also the Holocaust Memorial in Miami Beach opened in, I think, 1990 and the memorial is monumental—I think I just read it's 42 meters tall.

And in her photograph of it, she doesn't take a photograph of the monumentality of it; she focuses on a little girl who has walked up to these figures in the monument. It's a figure holding a child, and this girl walks up and touches the child on the head. And this image, she wrote that it was, if not her favorite or most important photograph, one of the most important photographs to her. And from that, she also got this idea of missing generations…

JWA: I was going to ask why she chose to call this collection “Missing Generations.”

Susan: In some of her writing, she ties it back to her own childhood, her identification as a child with children of the Holocaust—you know, having seen those photos when she was very young. So it's so personal for her. For her, the missing generations were those children who never grew, because of the 1.5 million children who died in the Holocaust.

JWA: I wonder what she would think about an exhibit of her photographs now, in the context of things that are happening in the world 30 years later.

Susan: Oh, yeah. She believed antisemitism still existed. It wasn't like it was a resurgence; it really had never disappeared. She was very conscious of that. And I think this would be what she would want to happen.

Missing Generations: Photographs by Jill Freedman runs until July 16, 2023. You can read more about the exhibition here.