From the Archive: Penny Yassour, "Mental Maps—Involuntary Memory"

What We Found

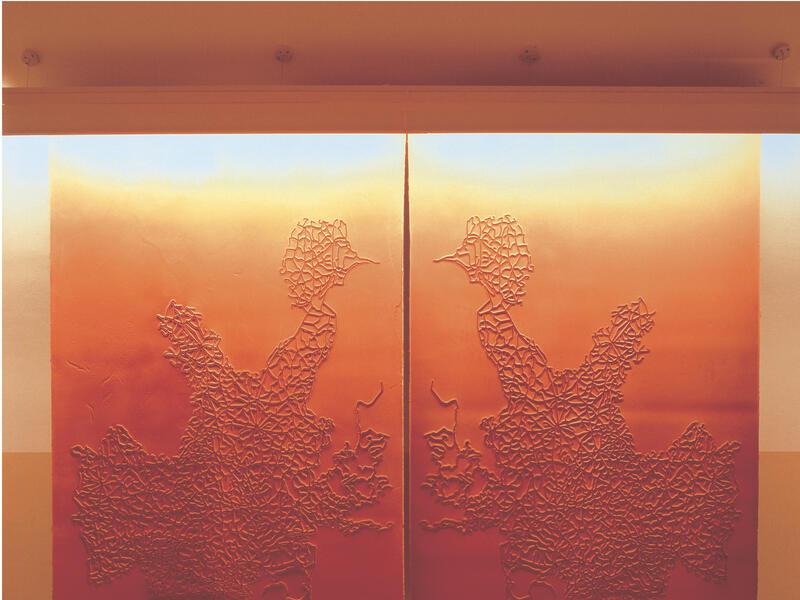

Mental Maps—Involuntary Memory (1997) by Penny Hes Yassour is a puzzling piece of art included as part of the Posen Library’s contemporary anthology of Jewish culture and civilization. It depicts mirrored images of a 1938 German railway map in rubber, pigment, and neon lights. The left panel contains two lines of text that read “North is West” and “[I am imprinting it down, because of not being able not to.]” and the right panel reads “East is South” and “Railway map, Germany 1938.” The mirrored maps gaze at one another. The neon lights illuminating the map's surface generate a slightly ominous, gradient effect that glows.

Yassour lives and works at Kibbutz En-Harod Ihud and teaches at the Bezalel Art Academy in Jerusalem in the Architecture and Interdisciplinary departments. A multidisciplinary artist, Yassour explores the boundaries between remembering and forgetting. Born in 1950, five years after the conclusion of World War II and the Holocaust, this work of Yassour’s recalls a mental map she was far too young to remember. Still, the anxiety generated by this remembrance endures and even continues to grow. Mental Maps—Involuntary Memory exposes those memories that inhabit our minds but are not necessarily our own. As the artwork’s title describes, these memories are generated and recalled involuntarily.

Why It Matters

Some might call what Yassour portrays in Mental Maps—Involuntary Memory “epigenetic memory,” the idea that genetic changes stemming from life events—particularly trauma—can be passed on to one’s children, or that our genes have memory. In the early 2000s, scientists began reporting that various environmental factors can influence chemical tags on our DNA, known as “methylation,” that turn genes “on and off.” In 2014, the idea of epigenetic memory captivated many in the Jewish community when Rachel Yehuda and her research team published the results of their study looking at the genes of 32 Holocaust survivors, all of whom were interned in Nazi concentration camps, forced into hiding during World War II, or experienced or witnessed torture. The study found that the children of some Holocaust survivors who experienced Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) had higher methylation of a stress response gene.

Scholar and geneticist Eva Jablonska acknowledges that, while the popularization of this research may lead to its exaggeration or misinterpretation, it has also opened exciting new opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration. While Yehuda and others’ research on epigenetic memory, in plants or mice, for example, is still preliminary and the source of some skepticism, it begins to offer a scientific explanation for what many, including Yassour, have long known to be true about themselves and their families.

The literary and feminist scholar Marianne Hirsch’s concept of “postmemory” is another way we might understand Mental Maps—Involuntary Memory. Hirsch explains that “‘Postmemory’ describes the relationship that the ‘generation after’ bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before.” The “second generation” as it is called, “remembers” experiences through stories they heard as children, or behaviors they observed among family members, or even images that they saw. But these resonated so profoundly that they seem to be actual, personal “memories.” Postmemory explains the memories held by the descendants of survivors in terms of the circumstances and experiences of one’s upbringing and family history.

For Hirsch, however, postmemory is less about remembering and more about “imaginative investment, projection, and creation.” In this way, Mental Maps—Involuntary Memory is an apt example of postmemory; it is not the act of remembering a memory, but a projection and artistic creation of memory.

Yassour explains that the doubled and reversed image in Mental Maps—Involuntary Memory “hints to the menacing image of the Third Reich Symbol,” a swastika, and “the double labyrinth imprinted on the screens is an exit-less spatial structure, spreading like an aimless cancerous growth. It was created from anxiety and re-produced it.” Yassour’s father fled Germany in 1933, and while it’s impossible to determine if and how much of the “anxiety” captured in Mental Maps results from gene methylation or a lifetime of stories and family history and culture, Mental Maps presents an opportunity to examine inherited and generational memories and traumas together with their ongoing influence in our lives.

From a historical perspective, Mental Maps—Involuntary Memory demonstrates how the recollection of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust continued to influence Jewish artists throughout the twentieth century. On her website, Yassour writes that for the 1938 railway map of Germany in Mental Maps—Involuntary Memory, “there is no need to explain the importance of this document for the forthcoming events.” Yassour’s belief that it’s unnecessary to explain the significance of the 1938 railway map reveals what is considered common knowledge about the Holocaust—in this case, the role of trains and symbol of the train car used in the deportation, displacement, and deaths of Nazi Germany’s victims. This artwork simultaneously captures the trauma, anxiety, depression, and PTSD that survivors of the Holocaust and other forms of anti-Jewish violence experienced in the past, along with the involuntary memories and (cultural or biological) inheritance of that trauma that their descendants experience today. Mental Maps—Involuntary Memory reminds us not only that we must never forget, but that it’s impossible for many not to remember. These memories continue to shape us and what we create.

Learn More

To learn more about the science of and debates surrounding epigenetics, check out Eva Jablonska’s article. Much of Penny Hes Yassour’s artwork with her commentary is featured on her website. If you’re interested in other artists whose work explores the Holocaust, including some of Yassour’s contemporaries, check out JWA’s piece on five women artists spanning the twentieth century.

This post is part of JWA’s From the Archive column. It was written in partnership with The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization.