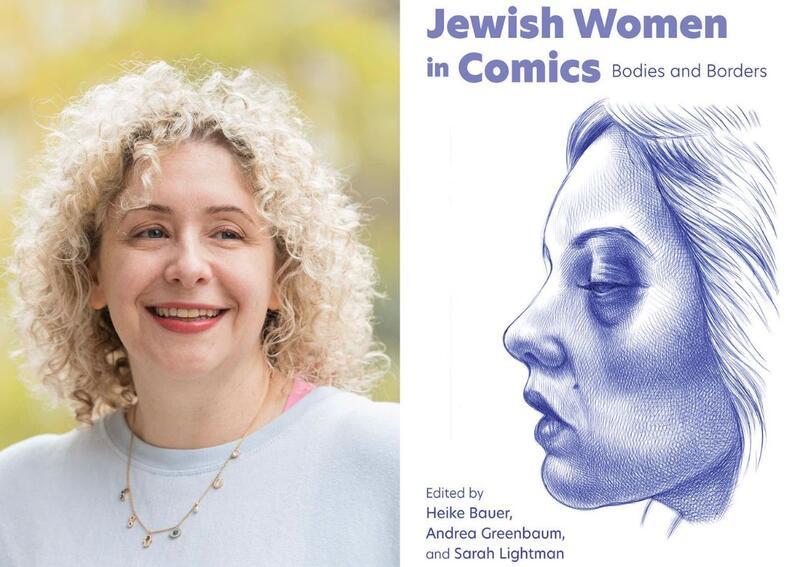

Q & A with Sarah Lightman, Co-Editor of "Jewish Women in Comics: Bodies and Borders"

In April 2023, Sarah Lightman, along with co-editors Heike Bauer and Andrea Greenbaum, published Jewish Women in Comics: Bodies and Borders. Featuring essays, interviews, and artwork from a diverse set of artists and scholars, this insightful and intimate collection analyzes the representation of Jewish women’s bodies and bodily experiences in comics over the decades. From discussions of miscarriages to queerness, readers are left to reflect on their own vulnerabilities, identities, and place within a patriarchal society.

JWA had the chance to speak with Lightman about the process of creating this collection, its most dominant themes, and Lightman’s experience and future in the field of Jewish women’s comics.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

JWA: In 2014, you edited the first book on Jewish women in comics, titled Graphic Details Confessional Comics by Jewish Women. Can you tell us about your personal journey within the field, and how you first got interested in this work?

Sarah Lightman: I started my journey as an artist. I was at art school, and I was looking for a mentor or a role model. I found it in Charlotte Salomon. I'm not sure if you've heard of her. She wrote an amazing work called Life? Or Theater? that tells the story of her family life in Berlin, and later, when she went into exile in the south of France to avoid the Nazis. It’s a story about family, mental health, and family secrets. I felt a deep connection to that work. Unfortunately, Salomon died in Auschwitz, but her work outlived her and is now an enormously celebrated piece of work.

Years later, after my MFA, I discovered comics. I was really struck by the work of 1970s Jewish feminist comics artists who lived in San Francisco. They drew their lives, their bodies, miscarriages, families, struggles, relationships, loves, and sexual experiences.

Then, I co-curated an exhibition which you just mentioned, Graphic Details. Often, access to the artwork can be very limited, so I knew I needed to edit this book to make sure the work outlived the exhibition in an accessible form.

I'd also started my own PhD in autobiographical comics. My approach to being a feminist academic is a very personal project. As I've grown older, I realize that academic work really can make an impact. You can change how comics are understood, read, and accessed, and I take it very seriously in that way. As a curator, editor, and a writer, I can change what's seen in galleries. I can change what's written and I can change what will be read. It’s a great place of power and privilege and a really good way of challenging versions of history that you may have been taught, and that, you realize, excluded a great many creative people.

In 2019, I published my graphic novel, The Book of Sarah, and after years of reading so many other people's stories, I felt increasingly free to tell my own story and to draw my life the way I wanted.

JWA: What was the process of compiling this collection? How did you and the other editors decide on the book’s organization, main themes, and who was featured?

SL: A special and important part of this feminist academic project is that we allowed ourselves as editors to follow our interests. Heike, whose work has a lot to do with gender and queer history, interviewed Israeli artist Ilana Zeffren, who draws her cats and many other things in her comics. Heike’s interest was not only in the cultural history in Israel, but also the animals, and Ilana's use of them to portray the inflammatory politics of Israeli life.

Andrea interviewed Emil Ferris. Ferris is a world-renowned comics artist, but many people don't know she has Jewish lineage. And so, Andrea’s interview was really interesting and eye opening where we learn about her kind of crypto-Jewish history. Emil kindly allowed us permission to use an image on the front of the cover, which I think really makes the volume very beautiful, and also gives us a lovely standing in the world of comics. It is wonderful to have her on our front cover.

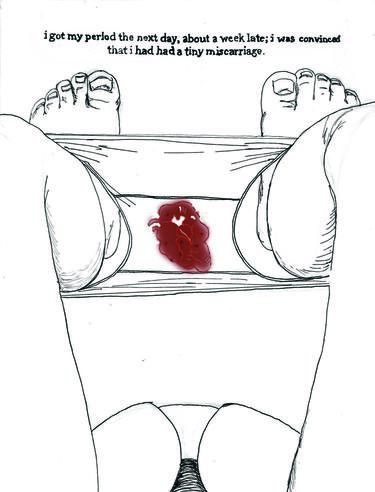

But when it came to themes, I was really excited to use an idea about bodies in it. One of the reasons I was [interested in the topic] was I was pregnant when I was editing [my first book]. By the time I was doing this, I had a son. I was experiencing my body in different ways, and I really wanted to see if the way I understood myself and my body was anything parallel to what was going on in the world of comics now or in the past. Pregnancy, miscarriage, and parenting: I wanted to see these on the pages, and also see how they looked in relation to the work that I was producing.

Interestingly, because everything was delayed because of COVID and our own various illnesses, the book grew into a book of our communal joint bodies. We had editors and family members who had [various physical and mental illnesses] and these are found on our pages. We find it very interesting that the book kind of became an indirect memoir project of our own lives, even though the works obviously were created separately. You can't help seeing how we're all growing in some kind of interlaced way, together.

JWA: One of the main subjects of this collection is “bodies,” more specifically focusing on Jewish women’s bodies and their bodily experiences through comics. What is the importance of this focus? How may these comics differ from popular comics or what the public is used to?

SL: Some of the works are quite explicit. We have Miriam Libicki’s “Sheretz,” which is a miscarriage comic, and you're quite struck by the bloodied knickers you see. This idea of underpants turns up quite a lot.

We also have toilet scenes. We have Helen Blejerman’s mother having meals with her in the toilet. These are all quite shocking and kind of impolite additions to what you might think comics might be about.

There’s also this idea of separation. We have the “Religious Mommy” comics by Adi David, and they show women in synagogue on the balcony, throwing sweets at someone who behaved badly to both of them. The men are downstairs. Women are upstairs. So, we're looking at these ideas of separation in reality, but also, of course, the comics page has its own structure of separations. It has boundaries, gutters, borders. Comic artists are using them or throwing away these separations to draw about moments of gender separation and women's lives in comics.

JWA: You’ve mentioned that the collection features a wide range of artists and scholars, including those from the LGBTQ+ community, those who deal with illness, and more. It also covers a wide time span, going back to the 1980s. What is the importance of this diversity within the collection? How does it expand the reader’s understanding of the subject matter?

SL: I love your question. I also love the idea that the 1980s is really far back!

When you teach or even when you're taught, what do you do? You get a textbook, right? And your textbook is the introduction you get on that topic. But what happens if that topic doesn't have diversity? You get a very flat experience. The joy of creating a collection is you're giving a new range of voices, a new range of artworks for people to look at. I think that's so exciting.

This, of course, is not the ultimate comics collection. It is a comics collection, a development from the one I did in 2014, and I hope someone else will do another one in the future with others as well. We could publish work that hasn't been translated before. So altogether, it’s thrilling to produce a collection that can be taught and hopefully people can resonate with.

JWA: What is the importance of comics as an art form, but also a form of political expression? How may it affect one’s relationship with their various identities?

SL: I think comics is probably one of the most democratic art mediums, because you don't have to be qualified, and you're distributing it. This is why I love to teach it. I love the idea that people become introduced to an art form that doesn't have a hierarchy. It's so nice, because our fine art world is complicated and worried about money and ego. Comics isn't like that at all.

I think it allows for people to belong who might not belong in other art spaces as comfortably. It also gives them a space to create work, even in the privacy of their own home, that can then become part of a wider conversation. That, I think, is a very beautiful thing as well.

Comics also gives you a space to be incredibly vulnerable to talk about private truths, to talk about things you're working through. You can be quite unselfconscious in it, because you don't have to have a kind of front. It gives people a wonderful permission, and I think that's why it's so political as well. Voices can be heard that maybe wouldn't be heard in other spaces.

JWA: I was really interested when I read there were artists featured from different countries. Were there any topics Americans touched on that Europeans didn’t and vice versa?

SL: American Jews are often a little bit more confident about presenting their Jewish identities and their Jewish experiences. There's a kind of an awkward navigation of Jewish identity for British Jews. But I suppose there's also a lot that's shared. There's trauma. There's the Holocaust. There's this larger Jewish narrative of Jews within history. There’s feminism. The way Jewish women are attacking and engaging with the patriarchy of the world they lived in.

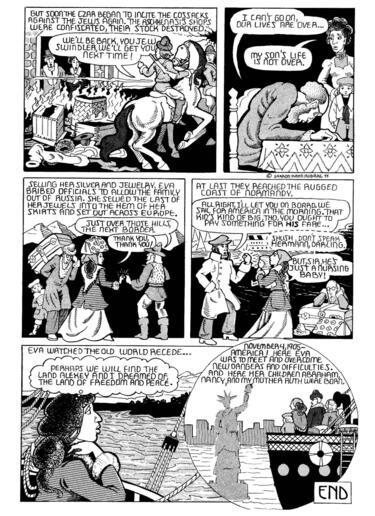

We have Sharon Rudahl’s comic, “Die Bubbeh,” about her grandma in Russia, who kind of rejects the patriarchy of a shtetl. It shows very visually the need to find a space where she could be the powerful woman she wanted to be, and it wasn't in that space then. So, this idea of what our identity is when we're in certain communities or in certain relationships, and what’s our relationship with Judaism. Identity, family loss, the loss of self through relationships: those are universal concerns, and we begin to touch on some of them in this collection.

JWA: How have you seen the field of Jewish women’s comics change over time?

SL: There's a lot of new scholarship coming out about Jewish women in comics, which I think is wonderful. Lots of really brilliant people in academia. A lot of women in academia, and that's a dynamic and really exciting space to be in. There are more publishing houses and more academic presses that will publish [comics], so that creates more scholarship.

I teach at the Royal Drawing School, and in my course, I talk about comics and performance—a kind of a new space with music and film. What could Jewish comics and performance be? We didn't really feature that in this volume, but that's a whole other area to look at. I'd be excited to see what scholarship might come from that.

JWA: What’s next for you?

SL: I did a PhD and [my dissertation] is called “Dressing Eve and Other Reparative Acts in Women's Autobiographical Comics.” I look at how women take biblical narratives and images that are misogynistic and support a patriarchal world, and how they transform them within their comics to produce feminist outcomes for the protagonists. One of them is Sharon Rudahl’s. Her Eve in the story actually lives a wonderful, full life at the end. She doesn't get banished and punished. It’s really exciting to see how these stories, which make me angry and uncomfortable, become much more palatable through these comics. My own graphic novel takes Sarah from the Bible and gives her a bigger life somewhere, a life beyond just producing a child.

I also created a series called “Biblical Domestic,” which I've been making since 2021, when I was overwhelmed by household chores during the COVID lockdown. I took women from biblical master paintings, and I stuck them in my kitchen doing the dishes or with lots of piles of laundry. I was trying to see if I could give them a life outside the paintings they were in, but they couldn't actually get out into the world. Not only for lockdown, but because they had to do so many domestic chores, they'd never get free of it anyway.

Now, I'm doing a series of large drawings and paintings about some of the worst parts of my life and my psyche. I’m focusing on things that are awkward and difficult, and those grubby moments and fears. I put them in the spotlight to enjoy each awkward moment.

I'm also making a series of new images about a menopausal Virgin Mary having a hot flush on the Underground [subway] as she goes to pick up Jesus after school. And I'm trying to think, how could I take these moments that I experienced privately and kind of perform them on a large canvas?