Q & A with Argentine Artist Mirta Kupferminc

JWA chats with Argentine artist Mirta Kupferminc.

JWA: What inspires your art?

Mirta Kupferminc: It’s an interesting question, as I believe inspiration, at least in my case, stems from experience. I would say that creativity—or what we often call "inspiration"—doesn't reside in the themes themselves, but in the metaphors we use to explore each subject. The themes that I approach are invariably rooted in experience. They emerge from the depths of my lived life or the stories that shape me. These narratives ALWAYS represent something far greater than just myself or my family’s stories, because I firmly believe that by capturing a fragment of a single life, you tell the story of many.

However, the real challenge lies more in the "how" than the "what" that is being conveyed. The style and the language—whether visual or verbal—are what transform a piece into something truly artistic. In this sense, I place immense value on the quality and execution of what I express. While we all share experiences, ideas, and emotions, the true difficulty lies in translating what we have individually lived, felt, or feared into something universally relatable, or at least representative of a group.

Each of us belongs to a “tribe,” and for me, a fundamental goal of my work is to tell stories that resonate with more than just my own perspective. It’s about creating connections and representing a broader human experience.

JWA: How does your Jewish identity appear in your art?

MK: I often say that one of the most significant events in my life happened before I existed. I was born in Argentina as the daughter of Auschwitz survivors who arrived clandestinely in 1948. It was a time when Jews entered Argentina covertly, yet Nazis were able to arrive legally.

My parents' stories of exile and immigration deeply shaped me, and the absence of my original family left a lasting imprint on me and I'm sure also on my offspring. Other immigrants who came after the war, alongside my parents, became my family, and I grew up in a world where Judaism was spoken about, but rarely practiced.

At the age of nine, I encountered a fifteen-year-old neighbor in the elevator of our building. She was a madricha (youth leader) at a Jewish institution, and she introduced me to the Ramah groups for children. I began attending with her, and later, my older sister joined as well. For my family, this marked a sort of return to Judaism, as we started learning about its traditions and rituals. My parents enjoyed the practices my sister and I brought home, despite the fact that we hadn’t received a formal Jewish education.

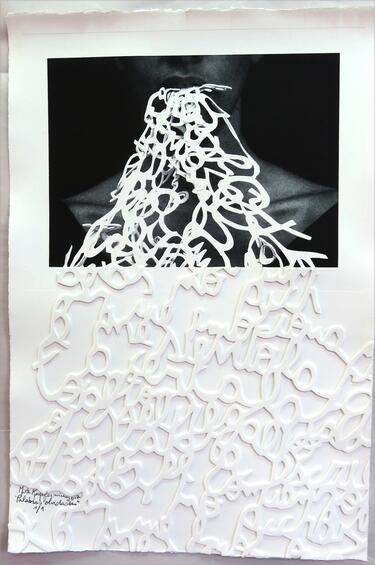

Jewish themes first appeared in my art when I was around 20 years old. At that time, I envisioned creating a book of original prints titled "Jewish Festivities." I wanted to share the beauty of Jewish celebrations with my Fine Arts classmates, as these traditions held a special place in my heart. Looking back, I know I would have approached such a project differently today. However, I believe that this work was pivotal—it marked the beginning of my journey into exploring and researching Jewish concepts through my art.

JWA: How can women artists promote other women?

MK: When an artist creates her work—or even reflects on the journey that led her to become an artist—she is never simply talking about herself. Inevitably, she is representing a larger group of people. The experience of being a female artist comes with its own unique challenges, and it differs greatly depending on the part of the world where the artist lives. Being a woman artist in Iran is not the same as being one in Latin America, as it is deeply influenced by the status of women within each culture and social group.

I firmly believe that living one's life as an example is a powerful way to inspire and uplift other female artists. In addition, the growing opportunities abroad (far more abundant now than they were in the past) are incredibly motivating.

Personally, I have always been an artist. I have managed to support myself through my work, whether by producing art, teaching classes, or mentoring other artists. I have two children, and throughout their upbringing, I never stopped creating, teaching, or guiding fellow artists. My children always understood how important my work was to me, and they respected that, as did my husband. I believe that the dedication and passion I have for my art might serve as inspiration for other women artists. I sincerely hope so, though I must admit it demands tremendous effort. You face countless obstacles, but it is achievable!

I would never have given up on motherhood, nor would I have abandoned my art. I feel deeply fulfilled knowing that I’ve been able to harmonize these fundamental pillars of my life.

JWA: Congratulations on your involvement with Jews of the Americas (JOTA), a new program at Brandeis. What is your vision for promoting Jews of the Americas through both the arts and scholarship?

MK: The program stimulates, inspires, and raises awareness of the profound and highly significant contributions and activities of Jews in the Americas as part of international culture.

This is a formal institutional initiative, and I emphasize "formal" because, while I have always had this interest on a personal level, the process of formalizing it and transmitting it to other artists began with my involvement in LABA New York, followed by the launch of LABA Buenos Aires. This project serves as a cultural laboratory for artists. It is specifically designed for artists, because we see them as generators of thought and culture—creators who amplify their impact by connecting with larger audiences.

In addition, my perspective as part of the Latin American Jewish Studies Association, has been unique. I’m somewhat of a rarity there, as the association predominantly consists of academics studying artists, while few artists are actual members. The use of English also presents a barrier; not all artists, particularly those of my generation, are part of organizations like the Memory Studies Association.

When Dalia Wassner, creator and director of JOTA, invited me to be part of the new program, we collaborated to establish this project with the idea of creating the first residency program for academics and artists focusing on Latin American Jewish topics. We are convinced that working together will be an immensely enriching experience. Academics often rely on images in their research, and we, as artists, draw on the knowledge and insights academics provide through their studies. So, we asked ourselves: Why not create a shared experience?

In October 2025, a four-day, in-person residency will take place at Brandeis University. Following the residency, participants will engage in six monthly online meetings, working from their respective countries of residence. Throughout this period, we will support each fellow in developing their project. The program will culminate in an academic publication and exhibitions showcasing the works produced during the residency. A distinguished selection committee has already assisted us in choosing the ten fellows who will participate in this inaugural residency. We are thrilled and optimistic about the enriching experiences this initiative will bring.

JWA: Who have been your mentors and teachers?

MK: I was born to immigrant parents who survived Auschwitz; my mother was from Hungary, and my father was from Poland. After my birth, we lived in a neighborhood in Buenos Aires called Villa del Parque, where my parents worked tirelessly to build a new life. Our neighbors included a family who became a significant inspiration to me. Their teenage daughter, who was about fifteen years old and studying fine arts, captivated me. I often watched her do her art school assignments, and by the age of four, I already knew I wanted to dedicate my life to that field. At fifteen, I began studying fine arts at a specialized art school with unwavering determination.

From then on, instead of recalling specific teachers, I found myself reflecting on "encounters." The first encounter was a book of Torah illustrations in my parents' home, featuring works by Gustave Doré. I could spend hours poring over its pages.

Another formative "major encounter" was in the hallway of our house, which led to my bedroom. Hanging on the wall there was a painting of an elderly Jewish man threading a needle, a tailor rendered by an unknown artist.

It is clearly a reproduction of a great master's work, yet the skill of the copyist or artist was equally remarkable, as the technique was truly stunning. Every day before entering my bedroom, I would pause and spend long moments gazing at this painting. One day, my parents promised me that when I moved to my own home, I could take the painting with me— and now, it hangs in my house.

I also greatly admired Bosch, numerous other great masters, and contemporary artists as well. However, I believe the moment I truly understood art happened was when I came across an artist whose work did not resonate with my personal sensibilities. Yet, despite my lack of emotional connection, I found myself acknowledging its extraordinary craftsmanship, concepts, and talent. It was at that moment that I realized I could separate the objective value of art from my personal preferences.

JWA: Can the arts play a role in diminishing antisemitism and racism?

MK: This is a very difficult question…If you had asked me this before October 7, I might have thought differently. In light of recent events in Israel and around the world, I have come to see that antisemitism is a deeply ingrained hatred within society. I don’t want to convey a hopeless message, but I do acknowledge that Evil, as such, exists, and that the human spirit can vary greatly from person to person.

Art can be a powerful tool to bring realities to light, and what makes it unique is its ability to do so through metaphors. However, I don’t believe art has the power to change the world. I think its role is to raise awareness, provoke reflection, and spark meaningful conversations or discussions, which is already immensely valuable. Unfortunately, though, I believe art can only reach and influence those who are open to it.

When prejudice and hatred are deeply rooted and have persisted for centuries, art serves primarily as a means to denounce, but I don’t think it can achieve much beyond that.

JWA: What advice do you have for women artists?

MK: My advice is that only by staying strong and remaining true to one's convictions can one achieve their goals. It is essential to have clarity about what you aim to accomplish and communicate. I believe we should avoid placing ourselves in a position of victimhood and recognize that, most of the time, the progress we make in breaking down prejudices and achieving our goals depends on us.

We must actively demand equal rights and opportunities. Thankfully, this is happening more and more, with increasing opportunities being offered to minorities, groups that societies have historically tried to overshadow or even ignore.

I firmly believe the world would be a better place if it were run by women, not because I undervalue men, but because I am convinced that women bring a unique and vital perspective to the table.

JWA: Tell us about your upcoming exhibits and projects.

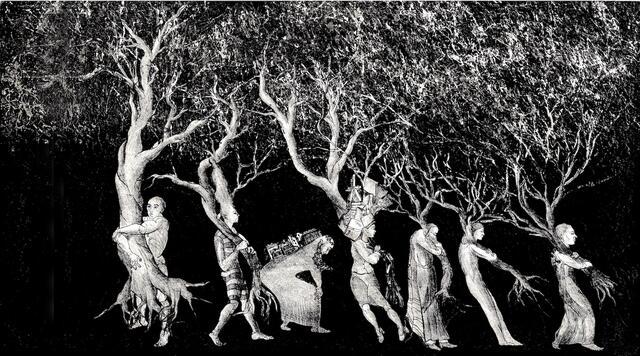

MK: I have been working for the past two years on a large-scale exhibition that will be presented in Buenos Aires at a stunning new art center currently under construction, called Zonderflag. It promises to be an intriguing exhibition, serving as a kind of "atlas" of immigration in Argentina. The project is based on photographs of women, children, and families that I have been collecting from the trash bins on the streets since I was a child.

While growing up, there were no family photos in my home, as my parents, like many others, sought refuge at the end of World War II. This absence is what sparked my deep fascination with photography.

In July of 2025, I'll exhibit some of these works in Prague as part of the Memory Studies Association conference. Additionally, my work will soon be displayed at the Jewish Museum in Munich, coming from the Jewish Museum in Vienna. Also at the Nahon Museum of Italian Art in Jerusalem, several of my pieces will be featured in an exhibition this year, as part of a project developed by the artists of Beit Venezia.

I am currently writing an art memoir that will be published next year and also collaborating with a Philadelphia scholar on another book that delves into the theme of ghosts and spirits in my corpus of work.

Next year, I will have a retrospective exhibition at the Jewish Museum in Buenos Aires, and I will also be part of the curatorial team for an exhibition at Palacio Libertad in Buenos Aires of an exhibition that will showcase a version of the Jerusalem Biennale, presenting some of the most exceptional installations from previous Biennales by international artists, along with the works of Argentine artists who have participated in its various iterations throughout the years.

Alongside these projects, I will continue teaching, mentoring, and cherishing life with my loving family.