Jewish Diaspora in the Borderlands: An Interview with the Tucson Jewish History Museum

On November 21, 2019, Dr. Scott Warren, a volunteer with the desert advocacy group No More Deaths was acquitted on felony charges of harbouring. In January of 2018, Warren had encountered two men from Central America seeking care in Ajo, Arizona—located roughly 40 miles from the US border with Mexico. He and the two men were arrested by Border Patrol agents; the original charges of harbouring and conspiracy to harbour carried a maximum sentence of up to 20 years in prison. His first trial, held in May of 2019, ended in a hung jury. The decision of the US government to pursue the retrial of a humanitarian agent felt representative of the current government’s relentless, brutal crackdown on migrants—but the trial also opened up discussions nationwide about injustices that residents of the Mexican/American borderlands have witnessed for decades.

I moved to Tucson in 2018 and got involved with No More Deaths a few weeks after arriving (as a point of disclosure, in the early fall of 2018, I became a staff member and worked as Media Coordinator for the group until late summer 2019). It was through my organizing work that I first encountered the Jewish History Museum and met Josie Shapiro, the current Zuckerman Fellow Curator of Community Engagement for the space. After Warren’s trial ended, I got in touch with Shapiro to conduct an interview about the Jewish community in Arizona, the relationship Judaism has to migration justice, obligations for residents of the borderlands, and how the Jewish History Museum in Tucson has evolved as an advocacy space.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length.

When I visited for the first time in May, I spoke with Ariel Goldberg, then the Curator of Community Engagement, about the origins of the Jewish History Museum’s synagogue space, but would love to dig a little deeper into some of the programming history. How has the museum’s programming evolved to reflect the wishes of visitors since its inception in 2005?

Our museum is simultaneously the oldest and the newest Jewish space in Southern Arizona. When our museum was reenvisioned with the opening of the Holocaust History Center in 2016, there was a desire to build a different type of Jewish space in Tucson. The permanent exhibition in the Holocaust History Center is titled Intimate Histories and focuses on the personal experiences of hundreds of survivors who made their homes in Southern Arizona following the Shoah. The concept is to house and hold their testimonies and their stories of not only survival, but also resilience and what came after the war. The exhibition is intimate and connective.

The goal is not to be a space where Jewish history is looked at in a vacuum, but to put that history into conversation with other histories. Our exhibitions in both the Holocaust Center and the Historic Temple facilitate an exploration of how Jewish people have shaped the places they dwell and how they have been shaped by them. That history is not without pain, loss, or suffering. We’re turning away from the practice of focusing inward, a traditional approach to culturally specific museum presentation, and instead turning a Jewish lens outward to the world around us.

The history of the Historic Temple building and the neighborhood in which we are located is a source of inspiration for our exhibitions and our programming. The building was an active Reform Synagogue until the mid-20th century. One of the last rabbis to lead the congregation in our building was Rabbi Joseph Gumbiner, who served the congregation during the 1940s. During another time of global antisemitism and violence against Jews, Rabbi Gumbiner chose to turn his lens outward and build relationships of solidarity with our neighbors at the AME Church, Prince Chapel, Tucson’s first African American Church. That church is still active, and we currently coordinate and work alongside their pastor, Rev. Dr. Margaret Redmond. In the 1940s, when Jews had their own grave concerns, Rabbi Gumbiner knew the strongest course of action was to act expansively, to engage in relationship building, and to pursue justice not just for Jews but for all marginalized people.

That legacy serves us now. Our Holocaust History Center includes a Contemporary Human Rights gallery, which has a new exhibition every year. In the past, that content has included highlighting violence against Rohingya Muslims and violence against LGBTQ+ folks. This year, our exhibition ASYLUM: To Address a Chaotic Circumstance of the Government’s Own Making focuses on asylum seeking at the Mexico/US border. Needless to say, it’s pretty relevant for us here in the Borderlands.

That is another vital aspect to our approach: We want to be aware of the place in which we dwell. The Yiddish term doykeit or “hereness” is embedded in what we are doing. We are located in the Borderlands of the United States, which is a unique political and social place. When I am thinking about programming that is ever-present in my process. How do I relate to the place in which we dwell? How do I turn my own Jewish lens outward?

Jewish diaspora is a complicated and painful thing, but it is also a beautiful thing. The diaspora gives Jewish people a unique relationship to place, to identity; and that sense of doykeit is a source of power. The Jewish diaspora in the Borderlands? That’s fertile ground to dig into, to explore. We want to do that in the work we do, in the programs we curate, and in the education we offer the community.

As the Scott Warren trial got underway, it was incredible to see a strong, radical Jewish presence at the courthouse and on social media. Can you go into detail about how you understood the role of Jewish Tucsonans during such a critical moment for those advocating safe passage through the Borderlands?

So much of the content of our museum galleries is related to the experiences of forced removal, relocation, assimilation or the refusal to assimilate, resistance, and resilience. The Holocaust History Center covers the origins of the current international laws and guidelines for refugee and asylum status, which were born out of the pain and horrors of the Shoah. “Never Again” has been the rallying cry for Jews around Holocaust memory and historical preservation for many decades. It is a natural extension of Jewish values and the legacies of the Shoah to ensure that “never again” is for everybody, especially right now. When you speak to most American diaspora Jews they strongly identify with an immigrant experience. We wanted to draw out those connections for Jewish people in Southern Arizona in a way that not only led to deeper understanding of the current climate, but toward action and response.

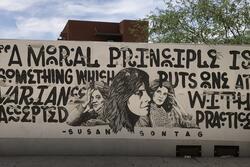

Tucson was the birthplace of the Sanctuary Movement in the early 1980s, and the Jewish community was heavily involved in that, working with interfaith coalitions. On August 12, 2019 (marking the two year anniversary of the resistance to the Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville, Virginia and just days following the massacre in El Paso), we held a press conference at the Museum. We took a very public stance aligning ourselves with the national movement of Never Again is Now and connected that to the history of Jewish participation in the sanctuary movement. We hung a banner on the front of the Museum, visible to passersby, that stated “No Human Being is Illegal,” which is actually a quote from Eli Weisel at the Sanctuary Symposium held in Tucson in 1985 at Temple Emanu-El. Weisel said that in response to migrants from Central America seeking refuge in the United States. That is Jewish history. Those are Jewish values in action. Never Again, Para Nadie—that is a natural extension of Jewish values.

People do ask us questions like “What’s Jewish about borders?” “What’s Jewish about this exhibition?” I respond the same way every time: For thousands of years, Jews have held onto sacred texts that implore us to welcome the stranger, to house them, to offer them respite. The Torah is as Jewish as it gets, right? The Torah tells us 36 times to welcome the stranger. In our ASYLUM exhibition, we have a quote from Pirkei Avot: “You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to desist from it” (2:21). We feel strongly that it is inherently Jewish to pursue social justice through action and solidarity. We are drawing from powerful traditions, histories, and legacies to guide that work.

Social action is not typically associated with museums. That is something that we want to shift. We want to make our museum a place of activation. We want to create spaces for many types of engagement. We’re looking at our work as something very different from what traditional models have offered in the past, and that shift is well received overall.

What is the Museum looking forward to, programming- and activism-wise? Obviously, Scott Warren's trial was a watershed moment that put the desert crisis into sharp focus for a lot of folks locally and nationally. But as a long-term desert resident, what is the Jewish History Museum’s role in combating deaths in the desert?

We opened our 2019-2020 museum season with a gallery chat where Scott Warren spoke about the ideas of place and landscape in the Borderlands. I worked on Scott’s legal cases as a paralegal to his attorneys. I wanted to bring Scott into the Museum to speak, not about his legal case, but about his work as a geographer relating to the place where we dwell. He talked about how landscapes tell stories, but they also can conceal as much as they reveal. That opening talk set a tone for our programmatic season, not only because of our current ASYLUM exhibition, but because much of the work we’re doing through our exhibitions and content is complicating narrative.

The history of Jewish people in the Borderlands, let alone in the United States, can be seen from many different angles. The history of Jewish people in the neighborhood that our museum sits in, Barrio Viejo, can also be seen from many different angles. We want to celebrate history at the same time as present questions that allow our visitors to complicate the narratives on their own. We want to be careful that we are revealing: peeling back more than a hundred years of previous attempts to conceal messy or even ugly histories in this neighborhood.

Part of that effort occurs in the galleries, in our content. Other parts of that effort occur through promoting social action and deeper engagement in the community. We’ve woven into our programming opportunities for people to learn about the crisis of death and disappearance in Southern Arizona. The ASYLUM exhibition is not only a way to learn about the current situation for asylum seekers, but it is also a call to respond. We developed a primer of sorts that gives more information on organizations that people can connect with or support locally and regionally.

The Jewish History Museum is committed to being a queer-affirming, feminist space. Can you tell me more about this?

We have a focus on inclusivity in our work, yes. What we don’t want to do is create a checklist and say “We’ve got a queer program, we’ve got a feminist program, we’ve got a POC program.” We’re working to truly cultivate a space where queerness is welcomed and centered. There are queer staff members, like myself, and board members, which I think is vital to preventing that “checklist” or typical “nonprofit” approach to diversity.

Being awarded this fellowship position speaks to that view towards inclusivity as well. As I mentioned, my background is not academic or museum based. I’ve been a community organizer who’s waited tables and struggled as a single parent. These worlds have not previously been open to people like myself. That is changing, and that is powerful. It is vital to create the kinds of worlds we want to live in by opening them up to people who might not have degrees and published papers, but who have been doing the work in these places.

Change is often slow. However, we’re willing to take strong stances, like we did in August with the Never Again public statement. We are being clear about our values and our vision. People want to be a part of it. Those who aren’t quite sure about it are being given the space to come along with us and to bring themselves exactly as they are. That honesty and acceptance of messy or iterative processes will build trust. That trust is then the foundation for powerful changes.