Israeli Cinema, Feminist Style

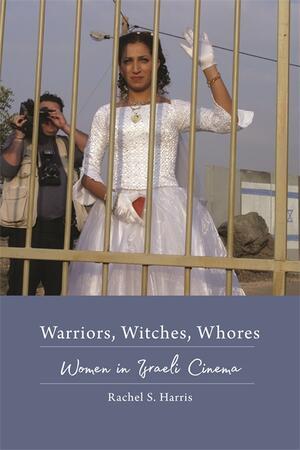

Cover image for Warriors, Witches, Whores: Women in Israeli Cinema by Rachel Harris. Published by Wayne State University (2017).

When we go to Jewish film festivals, we’re treated to an array of films from all over the world. However, even as films are internationally marketed, national film traditions and specific cultural contexts influence what we see on-screen. Rachel Harris’s new book Warriors, Witches,Whores: Women in Israeli Cinema focuses our attention on the shifting representation of women in Israeli cinema post-1990.

Warriors, Witches, Whores is an academic study and thus might not be an inviting text for general readers. Harris’s questions, however, are worth the consideration of every committed cinephile and feminist. She asks whether a director’s gender necessarily determines the politics of a film, whether women’s stories are necessarily feminist ones, which women’s stories are represented on-screen, and how some depictions of sexual violence intended to critique rape culture are actually complicit with it. For me, Harris’s Jewish feminist project is an act of welcome resistance to those who imagine that feminism can only position itself in opposition to all things Israeli.

In her introduction, Harris points out that while Hollywood in the U.S. had a women’s melodramatic film tradition to call upon (think Imitation of Life or Stella Dallas), no such tradition existed in Israel. She also makes clear, however, that from the beginning of Israeli cinema, women were depicted on-screen as military and pioneering support staff. Their bodies were metaphors for the land and their sacrifices were for the nation. The war widow was a prominent figure, and Israeli film shows that the Zionist narrative of gender egalitarianism was not sustained in practice.

According to Harris’s critical story, as more leftist critiques of Israeli militarism took hold in cinema, the possibility for raising feminist questions in war-related films developed. Changing modes of warfare also impacted the cinematic scene. Given that protection against chemical and biological agents during the Gulf War (1990-1991) depended on gas masks and sealed rooms, movies about that war could focus on domestic spaces and women’s stories. Two widely popular Israeli chick flicks represent this new women-centered war story: The Song of the Siren (1994, directed by Eytan Fox, based on the book by feminist Irit Linor) and Yana’s Friends (1999; directed by Arik Kaplun).

Directed by men and dependent on some of the conventions of the contemporary romantic comedy, these chick flicks are by no means feminist manifestoes in Harris’s view. In fact, she reads Eytan Fox as soft-pedaling the feminist politics of the book on which The Song of the Siren is based. Nonetheless, in these films, “men are cast in the role of lovers and not warriors” and “we also witness a new kind of female protagonist, one who can partner with a man but retain her independence [and] who does not require a man for protection.”

Similarly, Harris reads Amos Gitai’s Free Zone (2005), Eran Riklis’s Lemon Tree (2008), and The Syrian Bride (2004) as male-directed films that represent the Arab-Israeli conflict through female-female relationships rather than through cross-cultural romance. Notably, these films included Palestinian women in both the cast and the production crew and proved to be a training ground for such Palestinian directors as Suha Arraf (who co-wrote Lemon Tree prior to directing both Women of Hamas, a 2010 documentary, and Villa Touma, a 2014 narrative film). And in her discussion of the critically acclaimed, prize-winning Zero Motivation (2014), Harris questions the feminist politics of this film directed by Talya Lavie. On the one hand, this woman-directed film focuses on a group of less than stellar female IDF soldiers who could be read as exemplifying women’s lack of military prowess. On the other hand, defiance of military conventions and codes of behavior might be read as a female form of resistance to the masculine military machine that dominates Israeli society. By considering potentially different—and even diametrically opposed readings of the same film, Harris reminds us that viewers as well as directors influence the political meaning of a movie.

In later chapters of Warriors, Witches, Whores, Harris focuses on the increasingly diverse representations of women in Israeli cinema. While religious women tended to be stereotypically viewed from a secular vantage point, including a fetishizing of their sexual oppression, films such as Ushpizin (2004) and Fill the Void (2012) depict the struggles of religious women from an insider’s perspective. Harris acknowledges that these films, sanctioned by religious authorities, define their feminist limits within the world of Orthodoxy. Harris reads the career of Ronit Elkabetz, who received much praise for Gett: The Trial of Viviane Amsalem (2014) before her untimely death from cancer in 2016, as representing the shifting fortunes of Mizrahi women on-screen. She endured “years of insults hurled at her performances of the Mizrahi identity for which she was later celebrated.” And films such as Jellyfish (2007) include female foreign migrant workers (who support Israeli families while having their own sharply regulated) in the on-screen mosaic.

Harris argues that Israeli documentary and experimental narrative film offer alternative ways to represent rape. Israeli rape scripts—in film, courtrooms, and newspapers—have traditionally blamed the victim, offered her violated body as titillation, or reinforced a patriarchal mindset by casting women as in need of male protection. However, the documentary Brave Miss World (2013; directed by Cecilia Peck), focuses on Linor Abargil, who was raped shortly before being crowned Miss World, and her activist work to strengthen women-centered responses to rape. The filmed conversations between Abargil and other survivors highlight the second round of violence that many victims endure from social and legal institutions. Similarly, Michal Aviad’s Invisible (2011), includes archival records about the serial crimes committed by the “Polite Rapist” in the 1970s in this film about two fictional women, Lily and Nira, cast as his victims. The bonding and friendship that develops between these two women, the documentary that the fictional Nira edits about the survivors, and Aviad’s decision to overturn cinematic convention and focus her camera on the genitals of Lily’s lover rather than the women’s bodies all contribute to the feminist aesthetic of this film.

For Jewish feminists interested in the intersections of film, feminism, and Israeli culture, Harris’s academic study provides valuable questions and insights. Not to mention the book provides quite the watch list (most of the films mentioned here can be streamed either through Amazon or the Israeli Film Center).