India’s Jewish Silent Film Stars and the Power of the Outsider

For most of my childhood, I thought I was the only Indian Jew on the planet. Growing up in predominately white and Christian southern Maine, this misconception made me feel like a sparkly ethnic unicorn. Eventually, I relinquished my unicorn status when I learned that Jews came in all hues and from all corners of the world, India included. With the exception of more recent Jewish immigrants and converts, India is home to seven major groups of Jews: Cochin Jews, Chennai Jews with distant Sephardic roots, the Bene Israel community, Baghdadi Jews, the Bnei Menashe and the Bene Ephraim. While these communities are small, Indian Jews historically took up a huge space within the world of Indian cinema, especially during the era of early silent films.

Even pre-Bollywood, the screen was where cultural conversation in India took place. Traditional values and modern developments came to a head in film, so naturally early Indian filmmakers extensively explored the changing role of women in their society on the big screen. Finding actresses to present these issues and conflicts, however, proved difficult. It was considered akin to prostitution for a Hindu or Muslim woman to perform in public, never mind to play some of the scandalous characters screenwriters were creating. Jewish women, though, were not subject to this same code of behavior, and became the stars of the silent screen as well as the movement for women’s liberation, in part because of their unique outsider status.

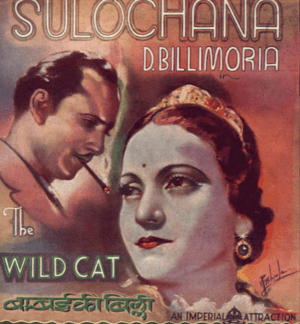

While Indian Jews were certainly the “other”––they practiced their own unique customs, were somewhat geographically isolated, and usually unable to speak Hindi––India was, and continues to be, one of the few places where Jews have integrated into the society without facing anti-semitism. Generally, Jews were accepted by their Hindu neighbors and were able to form their own communities without fear. That being said, the actresses of the time still took on Hindu or Muslim mononyms to appear relatable to film audiences, and thereby concealed their Jewish roots: Ruby Meyers became Sulochana, Florence Ezekiel Nadira became Nadira, Susan Solomon became Firoza Begum and Esther Victoria Abraham became Pramila.

These actresses lived lives that were, in many ways, far more autonomous than those of average Indian women. Pramila, a Baghdadi Jew, regularly played the role of “the vamp”, seducing and exploiting the men who fell prey to her charms When she wasn’t embodying the temptress, she was a daring stunt star. Pramila was also a rebel within her personal life–– to the horror of her parents, she eloped with a Hindu actor as a teenager.

She went on to marry a Muslim actor, Kumar, and raised her children in an interfaith household. In addition to being a model, actress, teacher, designer and the winner of the 1947 Miss India pageant, Pramila was the first major woman film producer in Indian cinema with thirty six acting credits to her name. Their perceived ethnic ambiguity and lack of religious limitations meant that Indian Jewish actresses were able to embody roles previously untouched in Indian films. Indian Jewish actresses portrayed women who openly flirted with men, drove cars, had jobs and lived lives of luxury. Sulochana, for example, played the part of a thief, Hyderabadi man, gardener, policeman, and blonde American bombshell over the course of the 1927 film, The Wild Cat of Bombay. This level of independence had never been portrayed before, and these images of liberation made it easier for female Indian moviegoers to envision themselves with glamorous and progressive lifestyles, like the ones “shown in the pictures.”

It is important to note that although Indian Jews were a religious minority, many of them benefitted from their comparatively lighter coloring which enabled their success in the film industry. To this day, colorism is an enormous issue in India. The cosmetics market is flooded with skin-lightening products like Fair and Lovely, and in some cases parents will show favoritism towards a light-skinned child, jeopardizing the self-esteem of that child’s darker siblings. Movies feature leads with fair skin and light eyes, while magazines turn brown skin ivory.

It was this combination of privilege and “other-dom” that allowed Jews to push the limits of Indian cinema. Their status in India is analogous to that of American Jews, who were usually somewhat able to assimilate, but remained fundamentally unique in the context of a country with Christian origins and influence. Actresses like Pramila and Sulochana, in their contributions to both Indian film and the feminist movement, are models for how Diaspora Jews of all races and ethnicities can use their outsider status to push boundaries. When one exists in opposition to the status quo because of her ethnicity, it feels more natural to also begin to question the significance of gender and other means of social stratification. Instead of being culturally confused or stuck between two worlds, the Indian Jewish women who transcended the limitations placed on who they could be––and all those individuals who are in some way “other”–– can imagine new selves and worlds beyond the confines of cultures that others accept.

As someone who considers herself doubly Diaspora’d, I have definitely experienced moments when concepts of identity or homeland have been perplexing and even distressing for me. Do I go to meetings at my college for students of color? How do I educate my Jewish community about issues pertaining to South Asians? But, when these questions of belonging are part of one’s everyday life, when we carry the weight of feeling like an outsider, a sense of clarity emerges that allows us to think more critically and carefully about the culture we take part in. I am not an average Jew or an average Indian. Why would I try to be an “average” woman, to conform to archaic rules and norms that have nothing to do with me? In the words of Whitman, “I contain multitudes”––as do we all. Why would I let anyone else tell me who I am, when they could never fathom all that I am? In one way or another, we are all other-ed. Instead of viewing this state of being as solely a challenge or obstacle, let us use our outside-ness to bring more people in.

Thank you for your article with your personal testimony on this interesting and utterly historical subject. I´ve added its link on a posting I´ve made on my edublogs sharing links about the topic.

very interesting, thank you for sharing; stretches my understanding of our Jewish world and our female experiences.