In Search of Jewish Voices from the Women’s Health Movement

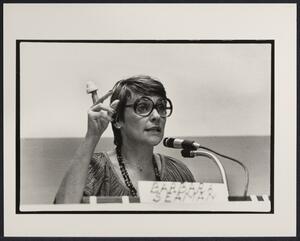

Lane, Bettye, 1930-2012, “Barbara Seaman holding vaginal cap at Pre-1980 Women's March press conference,” Catching the Wave, accessed February 7, 2019, http://catchingthewave.library.harvard.edu/items/show/221.

“Dear Diana,” wrote feminist sociologist Pauline Bart in December 1986. “I hope everything is going wonderfully well with you or at least as well as is possible under patriarchy.” And with that, my laugh interrupted the woodgrain tranquility of the reading room at the Rubenstein Rare Books and Manuscript Library at Duke University. Bart’s letters, from the radical to the wry, helped me build a lasting impression of Bart as a health activist and as a Jewish woman.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Pauline Bart wrote a lot of letters. To me, the letters are a window into Jewish women’s lives in the twentieth century. She wrote passionately for the inclusion of Jewish culture in multicultural programs and women’s studies. “American Jewish culture is very different from standard American culture as I can testify from my own experiences,” Bart wrote to a developing multicultural institute in the early 1980s, “I refuse to let my experiences continue to be erased.”

Bart’s concerns about erasure were not unjustified. The history of Jewish women within the women’s health movement is often overlooked or only known by those with an interest in Jewish history. Since the late 1960s, Jewish health feminists have helped redefine women’s health, patient’s rights, and our understanding of informed consent. My hope is that my dissertation will place Jewish women more prominently in the history of medicine as well as the history of twentieth century feminism. This project began a part of my senior thesis research at Northeastern University in 2011. Now, almost a decade later, this story is the basis of my doctoral dissertation at the University of South Carolina.

Although Bart’s personal and professional history is neatly preserved in the archives, many Jewish women’s stories from the women’s health movement are buried, if they are present at all. In the past year, I have visited archives at Harvard, Smith College, and Duke University to trace the work of Jewish women within the women's health movement from the 1960s through the 1980s. In my work, I take care to frame these activists simultaneously as American Jews and as American feminists in order to include the textures of their experiences beyond feminism alone.

Founding Members of the Boston Women's Health Book Collective, 1976. Back (L-R) Ruth Bell, Judy Norsigian, Vilunya ("Wilma") Diskin, Jane Pincus, Middle (L-R) Pamela Berger, Esther Rome, Joan Ditzion, Norma Swenson, Paula Doress, Front (L-R) Wendy Sanford, Nancy Hawley. Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at Harvard University.

As Barbara Seaman recalled, eight of the twelve founders of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, the creators of Our Bodies, Ourselves, were Jewish. Four of the five founders of the National Women’s Health Network were also Jewish. When I first heard this statistic, I could not help but ask, “Why?” How did so many Jewish women come to be leaders within the women’s health movement? Was it a result of trends within education and socioeconomics or something more? Something specifically Jewish? If the personal really is political, then surely the personal identities of Jewish women mattered, however, written histories did not provide much of an answer.

Historian Joyce Antler began the crucial work of writing this history, but Jewish women’s contributions reach well beyond what is recorded. There is more historical work to be done, more Jewish women’s stories to tell. I seek stories not just of the leaders, but also women who dedicated years of work “behind the scenes.” Driven to find the personal political narratives, I sought archival evidence of Jewish women connecting to one another as feminists, as women’s health reformers, and perhaps even as Jews.

Luckily, oral histories in libraries and resources from JWA guided me through the archives. I began by tracing the careers of Jewish activists through their names. Even if their own personal papers were not preserved, I found letters Jewish women wrote as members of larger feminist health organizations. I could follow the progress of health initiatives they championed. Archival records are important to this history because they work in tandem with more reflective sources like oral histories or memoirs.

Though I am in the process of analyzing thousands of documents from my trips, I am already finding evidence of health activists reflecting on Jewishness and feminist activism. Historians often speak of “silences in the archives,” but I find that my search for Jewish women is more about whispers than silences. It is about recognizing that identity does not necessarily present itself boldly; it is also present in the form of Yiddishisms and other small, yet meaningful references.

While a few women wrote reflections on their identities and their interest in women’s health, most stories were and remain not so easily found. Still, after flipping through hundreds of newspaper clippings, there it was: a vital, encouraging whisper in the records of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective. A Jewish Advocate article revealed that Esther Rome, a founder of the collective, engaged with the Jewish community as a moderator of a panel about Jewish ethics, abortion, and women's health. In other collections, I found evidence of a Jewish activist speaking to a Hillel chapter in Chicago about gender, power, and health. A thank you letter from the student group shows intergenerational connections between Jewish students and activists. I also found that some Jewish women who were active in health feminist circles participated in feminist seders in New York; they appeared on invite lists in Phyllis Chesler’s personal papers.

I hope this essay, alongside my more academic writing, can help nuance the history of feminism and show that Jewish activists were not Jewish on some days and health feminists on others. These identities intersected as evidenced in the archives, even in the collections of feminist health organizations with national reach. In oral histories, some Jewish activists note that the movement was about feminism and women’s health broadly, so there was not much discussion about the prevalence of Jewish women. However, who activists are matters to the history of this movement, especially when we consider the profoundly personal nature of health care and of the patient experience.

Though archives can provide links between Jewish identity and health feminism, written records alone cannot reveal all the intricacies of Jewish activists’ lives. Oral histories, memoirs, and personal reflections help fill in our historical blanks and show the dynamism of the women’s health movement. Whispers are helpful, but whispers alone cannot create a truly nuanced history. I encourage Jewish women and activists of all interests to participate in oral history interviews, whether you speak with me or other historians, and to consider donating personal papers to an archive. Perhaps then more Jewish women can have a voice that reaches out across time to shake up history, one library reading room at a time.

Special thanks to the fascinating women who have permitted me to interview them for this project. Thank you to the Rubenstein Rare Books and Manuscript Library at Duke University, the Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History at Smith College, and the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at Harvard University, as well, for allowing access to their collections.

I bought "Our Bodies,Ourselve"s as soon as it came out. Recently I gave it to my granddaughter. I did not know so many Jewish women were involved in its creation. I love that.