From the Archive: In the Ma’abarah by Ruth Schloss

What we found

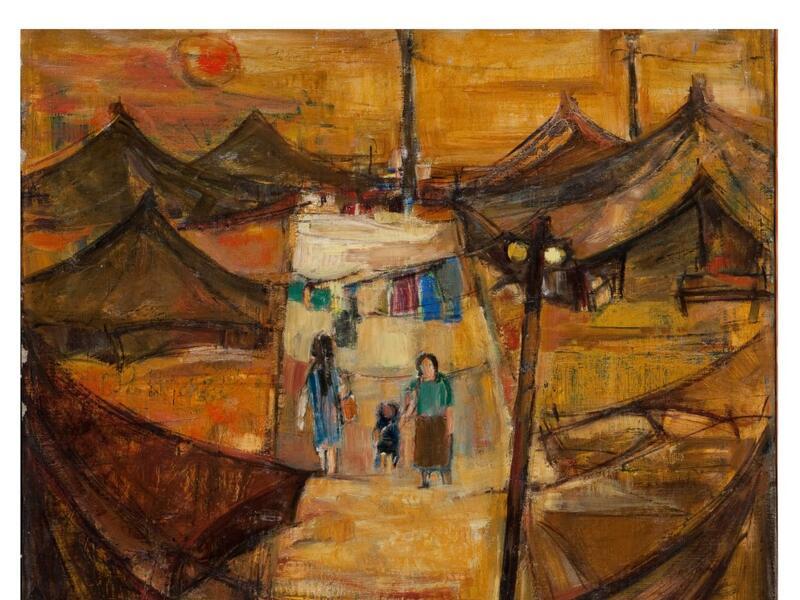

This painting, In the Ma’abarah by Ruth Schloss, from The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization depicts an immigrant and refugee absorption camp established by the young state of Israel in the 1950s: a ma’abarah (plural, ma’abarot). Schloss captures the claustrophobic conditions of the ma’abarah illuminated by a low, red-hot sun. The sweeping curves of the tents create shadows in the foreground of the painting. In the center, illuminated by a looming light pole, stands a mother and a child, facing the viewer, and another woman with her back to the painting’s viewer. The mother and child hold hands, their faces obscured. The central three figures, clad in bright clothing, are framed by warm-toned and shadowy tents. This family unit occupies the center of In the Ma’abarah, inviting us to consider the centrality of family in stories of migration and resettlement and the corresponding threats posed to family by the upheaval of relocation. Have they just arrived? Where did they come from? What did they leave behind? How long will they live here? Was there another parent, other children, or extended family, and where are they now?

While the initial influx of immigrants to Israel in the late 1940s, many of whom were Holocaust survivors, came from displaced persons camps in Germany, Austria, Italy, and from British camps in Cyprus, the majority of those sent to ma’abarot in the 1950s came from the Middle East and North Africa. The ma’abarot—overcrowded, underfunded, marked by high rates of unemployment among inhabitants, and often sites of conflict between Ashkenazi and Mizrahi Jews, and occasional intra-communal conflicts, such as those between Iraqi Kurdish Jews and Iraqi Arab Jews—became perhaps the most salient symbol of the early Mizrahi immigrant experience in Israel. By 1951, there were 127 ma’abarot that housed—often in extremely poor conditions—250,000 people, 75% of whom came from Arab lands.

Why it matters

Ruth Schloss, born in Nuremberg, Germany in 1922, fled Nazi Germany for Palestine with her family in 1937. They settled in Kfar Shmaryahu, an agricultural settlement. Schloss enrolled in Jerusalem’s New Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts, where she studied painting under Mordechai Ardon. Schloss participated in the kibbutz movement throughout the 1930s; the Communist Party and Soviet Socialist realism influenced her artwork. In 1942, after completing her studies at Bezalel, Schloss joined a training group at Kibbutz Merhavia and helped establish Kibbutz Lehavot Habashan in the Upper Galilee two years later. A member of Mapam, the United Workers’ Party, Schloss designed the party’s emblem. She also illustrated children’s books and drew for newspapers like Al HaMishmar and Mishmar LeYeladim, using this income to fund her education at the Académe de la Grande Chaumiere in Paris between 1949 and 1951.

Her work, including In the Ma’abarah, focuses on the human condition and carries a charge of social criticism and political commentary. Schloss sought “to give concrete expression to the tension between the wish to paint ‘whatever I feel like’ and the need to consciously respond” to the world around her. According to Gila Ballas, curator of a 1998 exhibit, “Social Realism in the ‘50s, Political Art in the ‘90s,” at the Haifa Museum of Art, many knew Schloss as the “Israeli Käthe Kollwitz,” a label ascribed because of the similarities of Schloss’s work to that of the German-born artist who used painting, printmaking, and sculpture to depict the impact of hunger, war, and poverty on the working class.

The Israeli art historian Tal Dekel argues that Schloss and Kollwitz share a connection not only in their place of origin, subject matter, and technique, but also in the feminine aspects of their work. Both produced art depicting impoverished women, mothers struggling to care for hungry children, women who lacked homes, and young women doing difficult manual labor. Their pictures, Dekel explains, “include the problems to which only women are prone, such as multiple births, as well as the special relations they maintain among themselves, and particularly the powerful bond between a mother and child.”

In the Ma’abarah captures this bond. The viewer does not know if there is another parent, other children, or an extended family network—this parent and child walk hand in hand with only one another. This particular painting, however, does not necessarily depict a woman in distress. The family portrayed is affected by the camp’s systemic harm, but can also be seen as entering a new world and a temporary home with resilience. Mother and child, though perhaps afraid, walk forward. Although the ma’abarot were sites of suffering and subjugation, Schloss suggests that they also produced activism, organizing, and new beginnings.

Learn more

To learn more about Ruth Schloss’s historical context and her contemporaries, check out this JWA article on artists and the Yishuv in Israel. This 2019 documentary, Ma’abarot, depicts the unfolding story of the Israeli transit camps, and you can see photographs of the ma’abarot on the National Library of Israel website.

This post is part of JWA’s From the Archive column. It was written in partnership with The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization.