A Fringe of Her Own: An Interview with Tamar Paley

Tamar Paley is an Israeli artist and jewelry designer. I interviewed her this spring about her project, A Fringe of Her Own: A Collection of Ritual Objects for Women, which is currently on view at the Kniznick Gallery at the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute in Waltham, Massachusetts.

Tell us about your background.

I grew up in Jerusalem in a very progressive community. As a teen, I began to understand that my experience was unusual. The fact that I had a bat mitzvah in which I read from the Torah and made my own tallit––these were not things that other girls were doing. For my friends and me, the uniqueness of our experience as Progressive Jews in Israel became a big part of our identities.

Ever since high school, Judaism has been part of my art. I was an art major in high school and even then, I would be creating pieces and suddenly incorporating all kinds of biblical verses. When I started to study jewelry design, I kind of kept my religious identity on the down low. My school, Shankar, is a very secular, liberal, artsy place where we just didn’t talk about Judaism.

As I was approaching my final year of school and starting to think about my thesis project, I decided I wanted to use this opportunity to say something about issues that matter to me. And it just hit me: I'm going to make ritual objects for women. I’d get to talk about feminism and women’s issues and religious pluralism, and I’d do it through objects that connect to the body. That tied together everything I’d been studying about jewelry design and using different materials and Jewish text and all these things that I love. It was just perfect.

Some of my teachers, though, were surprised. They said, “Oh, you’re religious? How did we not know that? And if you’re not religious, why do you care about ritual objects?” I explained that these are issues that I think about and care about a lot. I’m not religious in the way that they understand that identity, but I do feel deeply connected to Judaism––it’s a big part of my life. It felt like I was coming out as a Progressive Jewish woman.

How do you understand the relationship between jewelry and ritual objects?

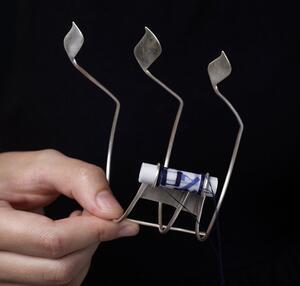

I like the connection between ritual objects and silversmithing. It goes way back––kiddush cups and candlesticks and menorahs and all that. So the craft within this field of ritual objects has always been there. But the objects that I chose to work with were mainly those that you wear: tallit (prayer shawl), tzizit (ritual fringes), and tefillin (phylacteries). I chose these pieces because they are the most controversial for women. The ritual objects that we use in the home are a little less gendered and more widely used among women. But we still have a hard time with the ones that are worn in public and on the body. And that really tied in with jewelry: how does this object that I choose to wear affect me and how I am choosing to present myself? How can I wear it and where can I wear it?

From a technical perspective, I took apart these ritual objects and rebuilt them to be modern and desirable––something that a woman would see and want to wear. I wanted to take away the controversy surrounding these objects. For me personally––even as a woman who grew up in a really progressive environment––I have a hard time wearing a kippah or putting on tefillin, so I wanted to understand my own discomfort and offer some alternatives.

What was your process in creating the objects?

I started from the conceptual: if women had a say in the creation of these ritual objects, how would they look and feel? I began by trying to figure out how women around me today are experiencing their spirituality. And as a jewelry designer, I was also thinking about how this material feels on the body, where it is worn, what are the gestures that come with wearing this object.

I wanted to give a voice to all the different ways that women in my life are experiencing their Judaism. And I wanted to reevaluate what these objects mean and find out what’s relevant about them. So I sent out a questionnaire of ten questions to women in my network. I tried to get as wide a range of answers as possible. Receiving their responses was amazing! I was so overwhelmed and moved by everything these women wrote. The biggest takeaway was that many women experience their Judaism in a private, inner way. I asked the question “If you could create a ritual object for yourself, what would it be?” A lot of women said it would be something they could keep private or expose at their will. So that’s why I started to create containers for the texts, and to focus on inner parts of the body, like the inner arm. For example, on the tallit piece ––where the text of the atara (the collar) is usually on the outside, in my piece it’s on the inside. I also played with typography so that the text wouldn’t be immediately legible.

All the texts that I use are pieces that women sent to me. Many are texts about gratitude and thankfulness, and also a lot of texts about guarding or protecting––which is really interesting considering the rise of #MeToo. It was also important to me to change all the text into language that was gendered feminine.

I thought a lot about the material, too. I searched for sources that dictated the requirements for the materials of ritual objects––you know, that would say, “this needs to be made out of leather” and have these specific dimensions. But I didn’t find many of those. The original texts say things like “it should be a sign on your hand and a sign between your eyes” but we don't necessarily have more guidelines for what it should look like. So that gave me permission to make changes. Maybe leather straps aren’t relevant anymore, in a time when not everyone is comfortable wearing leather.

Am I changing the essence of these ritual objects by changing their form? Can I feel more comfortable with the meaning of an object just by redesigning it? These were the questions I asked myself as a designer. Maybe if I altered the shape or the material, I could allow someone to reconnect with these objects. It may sound kitschy, but I believe I can make social change through my design.

What are the old and new elements that you incorporated?

I stayed true to handcrafted woven textiles––which I made with a colleague from the textile department––and colors of blue and silver. But then in some cases I changed the location on the body. For example, I adapted the tefillin head piece by moving it down from the forehead to the chest because the forehead felt so visible and so revealing, and that was not what the women I spoke to wanted. In some places I stayed true to the original text and in some cases I changed the text to respond to what women said they wanted in their ritual objects and what spoke to their Jewish values. A lot of the women I surveyed sent me Jewish texts but ones that had to do with universal values. So that was really interesting.

What was the response of your secular classmates and teachers?

They were totally into it. It was amazing. My advisors were women who are extremely secular, and whereas in the beginning they were like “Forget Judaism, just make jewelry!” by the end they thought this was an important project. They were part of this journey with me, and they were really supportive.

In Israel, if you’re a Reform Jew, you’re kind of in-between––you're not a hundred percent accepted by either secular Jews and or by the religious establishment. When I presented my project, I was worried that people be distracted by politics and not even pay attention to the work. But my professors reminded me that I wasn’t judging anyone’s beliefs or behavior, but rather showing a new way of thinking about these religious objects. And I think there is a real thirst for it. I had prepared myself for argument, and there just wasn't any need for that. People really got it. So the response was actually way more positive than I had expected.

As a designer, how do you relate to the pieces you created––do you think of them more as ritual objects or as jewelry?

At the end of the day, these are material things: it’s a piece of fabric, it’s a thread, it’s a box. I do think these pieces of material have real power, but we’re the ones charging them with this meaning––with the belief that just by covering your shoulders or head or wrapping something around your hands you are transported into the spiritual realm. I thought a lot about those gestures and the ways that these objects put us into a spiritual framework. I could be walking down the street, but if I cover myself in a tallit, am I in a holy place? People keep asking me if I would mind if my pieces were worn in a non-ritual context. I think I would feel weird about wearing a tallit just as an accessory, but ultimately these pieces are what you make of them: it’s a necklace, and you can decide what it means to you.

The most amazing conversations I’ve had so far are with people who have said “I can imagine giving my daughter this piece for her bat mitzvah and her wearing it.” Or “I really want to wear tefillin, but I haven’t felt comfortable, and maybe this kind of piece would make a difference.” I often wonder how far I can push the boundaries of the traditional objects and have the pieces still feel legitimate. But people have definitely expressed that they would use these objects, and that’s been really gratifying.

I really like the idea of women passing down these objects to daughters in the same way that a boy will inherit his grandfather’s tefillin or tallit. I think that we do that already with jewelry––so many people say things like “I can’t leave the house without my grandmother’s necklace.” We pass down objects in the same way that we pass down traditions. I want this to be work that encourages people to explore different ways of thinking about tradition and how they can make it their own. That's what it’s really about.

What are you working on now?

I'm still working on this project, actually––I just made a new piece the other day. And I'm working on a new project with two friends from school. We came up with this concept that the three of us would choose three objects and each of us would create a piece of jewelry that interprets those three objects. We based it off of the German saying “kinder, kuche, kirsh”––that women’s place is in the kitchen, church, and with the children. So for the three objects, we chose a coloring book, a set of measuring cups, and a pregnancy test. We’re thinking about calling it “Me Three” ––three objects, three women, #MeToo… I'm excited about that project. It lets me continue to work on women’s issues, which are very much on my mind. So it should be fun!

“A Fringe of Her Own” is on exhibit at the Kniznick Gallery at Brandeis through June 22, 2018