Trying Tefillin At Camp

This summer, I’m back working at Camp Ramah in Palmer, Massachusetts, which is affiliated with the Conservative movement. I used to attend as a camper, when I was growing up in the suburbs of Boston. Now I come with my sons from Miami to absorb Judaism, play Frisbee, and be free from electronics for the summer.

Some things about camp never change––swimming in the lake, singing birkat hamazon (grace after meals), daily morning prayers, sports, and the art room. The camp's philosophy regarding Jewish religious observance is both rigorous– campers are expected to observe the laws of kashrut and Shabbat– and egalitarian. This year, the camp collected extra tefillin so that female campers and staff could experiment with wearing phylacteries during the tefillah. Starting at $200, tefillin are a serious investment, so synagogues donated old sets to aid the effort.

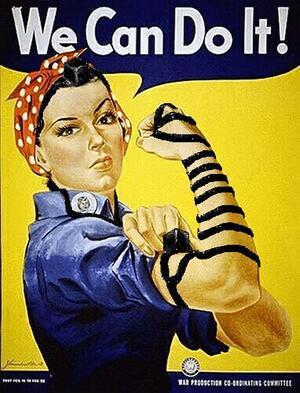

Generally used by men to perform a mitzvah, tefillin consist of two small leather boxes attached to leather straps. The two boxes each contain four sections of the Torah inscribed on parchment, including writings from the Sh’ma that pronounce Jews’ unity to one God. When wrapping tefillin, which is generally accepted as a male mitzvah, one of the boxes (the "hand Tefillin") is placed upon the arm so as to rest against the heart - the leather strap is wound around the hand, and around the middle finger of that hand. The other box (the "Head Tefillin") is placed, above the forehead. The Torah mentions wrapping tefillin: "You shall bind them as a sign upon your hand, and they should be for a reminder between your eyes."

I am by no means ahead of the curve in terms of being progressive with religious observances, but encouraging girls and women to wrap tefillin at places like Camp Ramah seems long overdue. Recently, at a women-only event, long-time camper and staffer Rabbi Ariela Rosen explained her approach to wrapping tefillin saying that once she committed to wrapping tefillin, it took her three weeks to feel comfortable and have the straps not fall off her arm. Rosen likened wearing tefillin to temporary body art. “It feels good on my arm,” Rosen said. “It helps me connect to tefillah [prayer]. I love the bumps it leaves on my arm.”

Rosen smiled at the memory of campers who wanted to touch the bumps the straps left. Demonstrating how to wrap tefillin on an excited volunteer, she showed how the straps created the word Shaddai, one of God’s names. There was an audible gasp and some people said, “Woah!”

“It can be powerful,” Rosen said, “I feel connected to this mitzvah.”

Later, a friend and I joined a teen group’s service where all the boys and male counselors, but only one female camper, wrap tefillin. A counselor very kindly showed us how to wrap the leather straps and say the correct prayers. It felt a bit awkward. The headpiece did not fit me exactly. I wrapped the straps correctly on my arm to spell Shaddai. Everything was in place by the time the campers recited the words of the V’ahavta – “You shall bind them as a sign upon your hand, and they should be for a reminder between your eyes." The often-recited prayer felt more meaningful for me that day because I too had wrapped tefillin on my own arm and between my eyes.

Author’s note: My views do not reflect those of Camp Ramah in Palmer, Massachusetts.