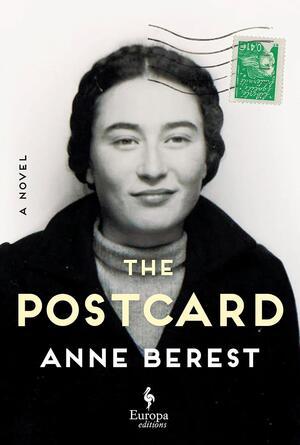

"The Postcard" Explores the Names We Carry

The Postcard unfolds like a flower, each delicately written layer revealing tender, difficult truths. A bestseller for years in France, the autobiographical novel is now reaching American audiences thanks to its 2023 English translation (done brilliantly by Tina Kover). Blending memoir, family drama, and thriller, Anne Berest traces her family’s history after her mother receives an anonymous postcard with just four names—Ephraïm, Emma, Noémie, and Jacques—written on it in a strange script. These are the names of Anne’s great-aunt, uncle, and great-grandparents, the Rabinovitches, who all died in Auschwitz; her grandmother, Myriam, was the sole survivor. As Anne hunts for documents, eye-witnesses, and other items that might help her identify the author of and motive behind the postcard, she recounts the Rabinovitch family story in painstaking—and apparently mostly true—detail.

As the book progresses, its ideas about trauma, identity, and violence deepen in complexity. But the book’s core lies not necessarily within the stories of the Rabinovitch family members' lives or even in the hunt for clues about the postcard, but rather in Berest's and her sister’s reflections on their ancestors’ influence.

“First Names,” a short section that interrupts the search for the author of the postcard, is a pair of real letters between Anne Berest and her sister, Claire. Anne discusses the implications of her and Claire's Hebrew names—Myriam and Noémi, respectively—writing, “We’re the Berest sisters, but on the inside, we’re also the Rabinovitch sisters.” She continues, “I’m wondering what I—you—we should do with these names. I mean… I’m wondering what we’ve done with them so far, and I’m wondering how they’ve affected us, silently, invisibly. Affected our personalities and how we look at the world.”

It’s a fascinating question that necessitates its own investigation. In Ashkenazi families, like Berest's, children are typically named (both in English and in Hebrew) after deceased ancestors, whereas naming a child after a living relative is taboo. (This differs from Sephardic custom, in which naming children after living family members is common.) In this context, the choice of names in the Berest family is confusing. Noémie died in the Holocaust, so her name is an appropriate choice, but Myriam was still alive when Anne and Claire were born. How can readers make sense of the choice to give Anne her name?

Several interpretations are possible. Most literally, the family’s secularism likely influenced their baby-naming rituals. Throughout the novel, Anne describes her mother Lélia’s hesitancy around Jewish practices: “...my sisters and I never once heard her say the word ‘Jew.’ She just never mentioned religion. It wasn’t a conscious or deliberate omission; I just think she honestly didn’t know how to address it, or even where to begin.”

Even more compelling, though, are the metaphorical implications of Anne being named after her then-living ancestor, the only one who had survived the Holocaust. Clearly, the Rabinovitch sisters’ names imprinted on the Berest sisters’ lives, and quite painfully, too. Anne inherited Myriam’s coldness, her ability to avoid danger. Meanwhile, the brevity of Noémie’s life manifested in Claire’s suicidality. As a child, she announced, “‘I’m the reincarnation of Noémie.’”

“Those Hebraic-sounding names are like a skin beneath the skin,” adult Anne writes to adult Claire. “The skin of a story bigger than us, that came before and goes far beyond us… they instilled something disturbing in us. The idea of fate.” Myriam and Noémie inevitably live on in Anne and Claire, their names and destinies tucked within each other like intricate nesting dolls. Perhaps Anne being named after Myriam, even while she still lived—long past Noémie—is just another reminder of the blurriness of the boundaries between the living and the dead. For the Berest sisters, this indistinction both immortalizes their trauma and facilitates their understanding of each other, their religion, and their family history.

But Anne Berest, in her exploration of historical and contemporary European antisemitism, eventually ruptures a trope so commonly found in modern-day Holocaust narratives: the ceaseless, swelling, inevitable currents of intergenerational trauma and victimhood. Toward the end of the book, Anne realizes she is pregnant. Her partner suggests that they name the baby after Noémie or Jacques. Anne firmly rejects this idea: “‘We’ll pick a name that belongs to them, and no one else.’” The legacy of names is too weighty, too painfully influential. Rather than desperately grasping onto the trauma and perpetuating or weaponizing it, Berest has agency. It’s up to her to decide how to tell her family’s stories, how to honor and transcend tragedy.

In its complicated approach toward names, identity, and trauma, The Postcard ultimately poses an expansive and timely question, summed up by Anne’s mother, Lélia: “‘Indifference is universal. Who are you indifferent toward today, right now? Ask yourself that. Which victims living in tents, or under overpasses, or in camps way outside the cities are your ‘invisible ones?'’”

It’s not hard to recognize the link between invisibility and namelessness. The Postcard implores its readers: remember and humanize and name the dead, then take their names and carry them—both in love and as a warning. Don’t clutch the names in a tight, insular fist, but don’t let them go, either. Instead, study their lives with wide-open eyes, holding them up to the light.