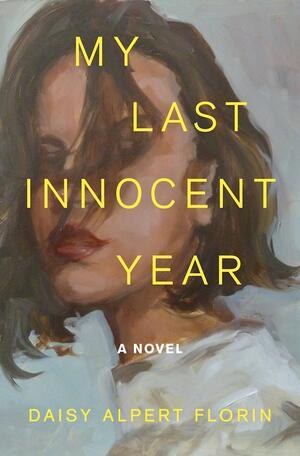

Ambiguous Womanhood in "My Last Innocent Year"

Content warning for sexual assault. Spoilers ahead.

I’ve lived in Brooklyn for over a year now, but I recently found myself on a park bench uptown, steps away from my alma mater as I finished reading Daisy Alpert Florin’s 2023 novel, My Last Innocent Year. Afterwards I avoided walking to campus and instead paced for hours along the river. I squinted in the sun and wished I’d thought to apply more sunscreen as I allowed memories to engulf me.

With a title like My Last Innocent Year, I initially assumed that the novel’s revelations would be stark, propelling the protagonist, college senior Isabel, from “innocence” into the sharp realities of adulthood. Yet there isn’t one major event that causes Isabel to lose her innocence. Rather, it’s a slippery series of experiences having to do with violence, power, and loss that alter Isabel’s sense of self and womanhood. Unlike other post-Me Too pieces of media, such as artless girlboss feminism movies or dismally reactionary shows like The Idol, My Last Innocent Year shines and resonates in its utter ambiguity.

The novel is definitely of the dark academia genre, with the first chapters outlining Isabel’s experience of sexual assault by former IDF soldier Zev. The two are bonded outsiders as some of the only Jews on a WASP-y campus. Both have been marginalized within the Jewish community—Isabel due to her blue-collar Lower East Side upbringing, and Zev due to his… being Israeli, I guess. (Mostly, he’s just an asshole, one of those guys who thinks it gives his personality depth to be misunderstood. But who among us hasn’t fallen for that type of posturing at some point—especially in college?).

When Zev sexually assaults Isabel, it’s clear to Isabel and readers that he crossed a crucial line. Debra, Isabel’s fiery, protest-prone friend, immediately plots to spray paint “RAPIST” on Zev’s dorm room door as an act of revenge. The book’s setting of the late 90s permeates the worldviews of the characters, and the era’s devastatingly misogynist lore looms in the background even as Isabel and Debra throw themselves into third-wave feminist activism on campus. However, although Zev’s assault easily fits our 2023 understanding of rape, Isabel spends much of the novel confused about what occurred between them. Contemporary readers know, even if the characters can’t always put words to it, that young women like Isabel are extremely vulnerable to the patriarchy’s subtle twists of violence and degradation. However, it soon becomes clear that the novel doesn’t function in order for readers like me to applaud our own virtues and foresight.

As Isabel begins an affair with the older and married professor R. H. Connelly, the book subverts, or at least complicates, mainstream contemporary feminism’s often clean-cut definitions of power and womanhood. The novel’s gray areas deepen and widen, forcing female readers to grapple with impossibly delicate questions about our agency in a patriarchal world.

To Isabel, Connelly is at first the polar opposite of Zev: he asks Isabel exactly what she wants and seeks her clear, enthusiastic consent. Isabel feels real pangs of guilt about the hurt she may cause Connelly’s wife and her own peers through their illicit relationship. At the same time, with Connelly she gains a striking understanding of her sexual and romantic desires and also develops as a writer under his wing. Meanwhile, she’s trapped in an ancient, hazardous arrangement: a young, ambitious, relatively inexperienced woman falls for the allure of an older and highly influential married man. It’s evident that Connelly’s apparently progressive actions aren’t so pure as he makes statements such as “I don’t want you telling a story like [Zev] about me someday… you don’t know what you might think about all of this later, when it’s over… We need to be clear about it now so there are no misunderstandings.” Connelly recognizes that there is a lurking power imbalance between them that skews the full meaning of Isabel’s consent.

To readers’ relief, Isabel finally ends the affair when she graduates college, shortly after she reveals Connelly’s secret involvement in a male colleague’s abuse of his wife and daughter. She begins to grasp his manipulation of her youth, gender, and eagerness. This realization is the closest readers get to a concrete definition of Isabel’s titular loss of “innocence.”

And yet, the novel doesn’t end with Isabel spurning Connelly, just as she never fully condemns Zev for his assault. Rather, she becomes obsessed with the expired relationship, analyzing its impact on her sense of self and career for decades, even until she learns of Connelly’s death. She struggles to parse a memory of his insistence that she was never a “victim” in their asymmetrical dynamic. Connelly had asserted, perhaps not totally incorrectly, that Isabel did carry some of her own power in their relationship.

Although this pronouncement is enraging coming from Connelly, it underscores a question that haunted me throughout the book: Can young women experience harrowing moments of manipulation and violence from men and still have agency in our romantic and sexual decisions, even when they are detrimental to ourselves and others?

My Last Innocent Year, despite its title, suggests that as women age, we don’t necessarily lose the vulnerability, desire, trauma, or emotional riskiness of our younger selves, even when those versions of ourselves are lost. The murkiness of womanhood follows us into the rest of our lives—just as Isabel is left longing for Connelly while also grappling with the meaning of their relationship.

My Last Innocent Year’s ambiguity makes it an angst-inducing read for someone in my shoes—a year-ish out of college, plenty of thorny decisions under my own belt, unsure of my place in the world, and dealing with my own experiences of guilt, hurt, and confusion. Is this just part of being in my twenties, or will the rest of my life be like this? Are we as women doomed never to get answers about people who, for better or worse, contributed to our lives in some formative way? How do we measure our development and empowerment in a world that makes it so complicated to do so?

That sunny uptown afternoon, after I finished the novel’s last chapter and paced around Riverside Park, I eventually opted to head back to my (wonderful, supportive, same-aged) boyfriend’s nearby apartment. I told myself I’d visit campus another time when I was in a better headspace. At that moment I felt that my college memories were overwhelmingly tender, a recent version of me itching just beneath my skin, her fading scars reopened by the book’s plot. As I walked away from the physical reminders of that time, I knew that I wasn’t walking away from her. She is still me, every part of her, even the parts I’ve outgrown. She bears bruises, she shows signs of blooming growth, she is becoming an adult (whatever that means) amidst the vast, cloudy tumult of womanhood. Like Isabel, she is—I am—still, always, growing up.