Gertrude Elion

"It's amazing how much you can accomplish when you don't care who gets the credit."

Gertrude Elion's accomplishments over the course of her long career as a chemist were tremendous. Among the many drugs she developed were the first chemotherapy for childhood leukemia, the immunosuppressant that made organ transplantation possible, the first effective anti-viral medication, and treatments for lupus, hepatitis, arthritis, gout, and other diseases. With her research partner, George Hitchings, she revolutionized the way drugs were developed, and her efforts have saved or improved the lives of countless individuals.

Courtesy of TWIi.

Although Elion herself cared far more about the practical outcome of her lab's collective work than about her own reputation, her achievements earned her one of the highest honors a scientist can receive: the Nobel Prize in Medicine. She overcame enormous obstacles to reach this pinnacle. Battling longstanding prejudices against women in science, she initially had trouble even getting a job, but a combination of brilliance, determination, and stubbornness brought her to the top of her profession. She was the fifth female Nobel laureate in Medicine, the ninth in science in general, and she reached this height without earning a Ph.D.

Elion worked tirelessly to convey the fun and excitement of science to students of all ages and to encourage children—especially girls—to pursue scientific careers. A warm, animated woman with a great love of life, she was also an avid photographer, an eager traveler, and a true opera enthusiast. Her achievements, her curiosity about the world around her, her generosity, and her concern for humanity make her not only a valuable role model for budding scientists but also an inspiration for all who wish to better the world.

Notes:

- Quote from "Gertrude Elion: A Legacy of Excellence"

(video), GlaxoSmithKline Inc. Heritage Center.

Thirst for Knowledge

In this 1999 interview, Chemist Gertrude Elion (1918 – 1999) discusses her eagerness to attend school as a young child.

Gertrude ("Trudy") Elion was born in New York City on January 23, 1918. Her father, Robert Elion, a dentist, had immigrated to the United States from Lithuania at the age of 12. Her mother, Bertha Cohen, came to America alone at the age of 14 from the part of Russia that is now Poland; studying English at night school, she worked in the needle trades before marrying Robert at 19.

From a very young age, Trudy displayed the qualities that would lead her to a Nobel Prize. Even before she started school, she wished to learn about the world around her. A voracious reader with "an insatiable thirst for knowledge," she was interested in everything around her. "It didn't matter if it was history, languages, or science," she later recalled. "I was just like a sponge."

As a student at the all-girls Walton High School in the Bronx, Elion was not yet focused on science. Exploring history, writing, and performing, she received the school's Cooperation in Government Award and a prize in American history; belonged to the History Dramatic Club, the Electron Science Club, and the Glee Club; and published an essay and a poem in the yearbook. Propelled by her quick intelligence, she skipped two grades and graduated from high school in 1933, at the age of 15.

Notes:

- Quote "an insatiable thirst for knowledge" from autobiography of Gertrude Elion on the website of the Nobel Foundation, accessed February 16, 2000; available at http://www.nobel.se/medicine/laureates/1988/elion-autobio.html

- Quote beginning "It didn't matter..." from Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles, and Momentous Discoveries (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1993), 286.

- Information on Elion's high school activities from "Gertrude Elion Memorial" (Video), March 27, 1999, GlaxoSmithKline Inc. Heritage Center.

The Turning Point

Courtesy of Bella International Productions, Inc.

Soon after graduating from high school, Elion found a focus for her widespread intellectual curiosity. Watching her beloved grandfather die painfully of stomach cancer and deciding "nobody should suffer that much," she dedicated herself to finding a cure for cancer. "That was the turning point," she later recalled. "It was as though the signal was there: 'This is the disease you're going to have to work against.' I never really stopped to think about anything else."

That fall, Elion entered Hunter College. Unlike many people of their era, the Elions never thought twice about sending their daughter to college. Trudy attributed her parents' emphasis on education to their Jewish background. "Among immigrant Jews," she said, "their one way to success was education, and they wanted all their children to be educated.... [I]t's a Jewish tradition. The person you admired most was the person with the most education. And particularly because I was the firstborn, and I loved school, and I was good in school, it was obvious that I should go on with my education. No one ever dreamt of not going to college. That never came up." Luckily for the Elions, who had suffered financially from the stock market crash of 1929, Hunter was free to those with good enough grades to get in.

In preparation for working on cancer, Elion majored in chemistry rather than biology because, as she said later, she wished to avoid dissecting animals. The all-female Hunter provided a supportive environment for studying science, and Elion commented later that it did not occur to her that there was anything unusual about her choice of a subject. "There were seventy-five chemistry majors in that class," she remembered. "[W]omen in chemistry and physics? There's nothing strange about that."

Notes

- Quote "nobody should suffer that much" from Interview with Gertrude B. Elion, March 6, 1991, Academy of Achievement, accessed February 16, 2000; available at http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/eli0int-1.

- Quotes beginning "That was the turning point...", "Among immigrant Jews...." and "There were seventy-five..." from Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles, and Momentous Discoveries (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1993), 287.

The Job Hunt

Courtesy of Bella International Productions, Inc.

In 1937, at the age of 19, Elion graduated from Hunter College summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa. Wanting to pursue a career in chemistry research, she applied to fifteen graduate schools. Despite her impressive academic record, however, not one would grant her the financial aid she needed to begin work on her Ph.D.

After being turned down for several laboratory jobs for which she was more than qualified, Elion began to realize the true source of her difficulties. Major obstacles lay in the path of women in science; with much of society believing that science was a man's business, hiring and admissions committees were unable to look beyond the fact that Elion was a woman to recognize her brilliance. "I hadn't been aware that any doors were closed to me until I started knocking on them," Elion later commented wryly. "Of course,...it was a very bad time to graduate. It was the Depression, and nobody was getting jobs. But I had taken that to mean that nobody was getting jobs."

Discouraged, Elion enrolled in secretarial school but lasted only six weeks, quitting to take a one-semester job as a lab assistant in a nursing school. Three months later, again out of a job, she began volunteering in a chemistry lab, enduring daily anti-Semitic jokes from the company president but gaining valuable experience. By the end of a year and a half, she was paid $20 a week, out of which she saved enough to enroll at New York University. The only woman in her graduate chemistry classes, she wrote her thesis at night and on weekends while working first as a doctor's receptionist and then as a substitute teacher of high-school chemistry and physics. In 1941, she received her Master's degree.

Notes:

- Quote beginning "I hadn't been aware...." from Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles, and Momentous Discoveries (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1993), 287.

- Remaining information from McGrayne, 287-288; Interview with Gertrude B. Elion, March 6, 1991, Academy of Achievement, accessed February 16, 2000; available at http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/eli0int-1.

Personal Tragedy

After graduating from college, Elion met and fell in love with Leonard Canter, a handsome young statistics major at City College. After he graduated, Canter received a fellowship to study abroad, and through the letters they exchanged, he and Elion fell even more in love. After he returned, they planned to get married.

In 1941, the young couple's dreams were shattered when Canter fell ill with acute bacterial endocarditis, an infection of the heart. A few years later, his illness would have been easily cured by penicillin, but at the time, little could be done. Six months later, Canter died.

Canter's death, like her grandfather's, spurred Elion's scientific drive. "It reinforced in my mind the importance of scientific discovery, that it really was a matter of life and death to find treatments for diseases that hadn't been cured before," she said. A decade and a half later, that message was again intensified in a very personal manner when Elion's mother died of cervical cancer in 1956.

Following her fiancé's death, Elion threw herself even more into her work. None of her subsequent suitors could ever live up to Leonard, and she never married. Her brother's children and grandchildren took the place of the children she never had; indeed, she called her niece and nephews "our children," occasionally even "my children." Her great-nieces and -nephews adored her, and one even referred to her as "my goddess."

Notes:

- Quote "It reinforced in my mind...." from Susan A. Ambrose, Kristin L. Dunkle, Barbara B. Lazarus, Indira Nair, and Deborah A. Harkus, Journeys of Women in Science and Engineering: No Universal Constants (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997), 136.

- Quotes about "our children," "my children," and "my goddess" from "Gertrude Elion Memorial" (Video), March 27, 1999, GlaxoSmithKline Inc. Heritage Center.

Burroughs Wellcome

By the time Elion earned her Master's degree, World War II was in full swing. With many male scientists now involved in the war effort, chemical laboratories were finally willing to look to women to fill jobs. Elion began working as a food chemistry analyst for the Quaker Maid Company, measuring the acidity of pickles, the color of mayonnaise, and the mold levels on fruit. After a year and a half, however, she was eager to find a research job. She found a promising position at Johnson & Johnson, only to see the lab close six months later.

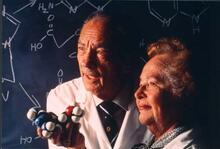

In June 1944, as Elion was weighing several job offers with which she was not quite satisfied, her father received a sample of painkiller at his dental office. Noticing that Burroughs Wellcome, the pharmaceutical company that made the drug, was located in nearby Tuckahoe, New York, he suggested Trudy inquire about a job. That Saturday, she was interviewed by Dr. George Hitchings. Elion was intrigued by Hitchings' research project; he was impressed by the young woman's intelligence and energy. Over the next decades, the Hitchings-Elion partnership proved immensely fruitful.

For the first time, Elion had a job she truly found intellectually stimulating, and she adored it. She voluntarily brought work home every weekend, and when once she came home empty-handed, her mother assumed she was sick. Conditions were often difficult; with the lab located directly above the dryers for an infant formula, Elion had to wear thick, rubber-soled shoes to withstand the floor's 140° heat. But the staff had water fights to break the heat, and Elion was thrilled that Hitchings encouraged her and his other assistant, Elvira Falco, to pursue their research independently. As she said in 1990, "I originally set out thinking, 'I'm going to stay here as long as I continue to learn.' Here I am, 46 years later and I'm still learning."

Notes:

- Quote "I originally set out thinking...." from Interview with Gertrude B. Elion, March 6, 1991, Academy of Achievement, accessed February 16, 2000; available at http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/eli0int-1.

- Remaining information from Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles, and Momentous Discoveries (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1993), 288-289.

Early Research

Courtesy of TWIi

Hitchings' and Elion's approach to their work was highly innovative. Contrary to most previous drug developers, who had depended largely on trial-and-error methods, they actively designed drugs based on knowledge of how cells worked. Although Watson and Crick had yet to discover the double-helix structure of DNA, scientists did know that cells need nucleic acids to reproduce. Hitchings theorized that by interfering with the DNA of cancer cells, bacteria, and viruses—which, because they need very large amounts of DNA to reproduce, should be particularly vulnerable to disruptions of their lifecycles - they could prevent the unwanted cells from replicating and thus stop the spread of disease. The goal was a drug that would disable the disease cells without harming normal cells.

Hitchings assigned Elion to work on the purines, two of the four bases that make up DNA. Elion created slightly altered versions of the purines, hoping to make one that would be similar enough to the real base that the disease cell would be fooled into incorporating it but different enough that it would be unable to use it to reproduce. "We used to call it a rubber donut," she said. "It looked like the real thing, but it wouldn't work."

Even as Elion became immersed in her research, she continued to aspire to the Ph.D. she had as yet been unable to earn. Enrolling at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, she commuted three nights a week from her job in Westchester County, to Brooklyn, and home to the Bronx. After two years, however, the dean demanded that she either work full-time on her doctorate or leave school. Unwilling to give up the exciting job that had been so difficult to get, Elion reluctantly gave up her dreams of a Ph.D.

Notes:

- Quote beginning "We used to call it...." from Interview with Gertrude B. Elion, March 6, 1991, Academy of Achievement, accessed February 16, 2000; available at http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/eli0int-1.

- Remaining information from Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles, and Momentous Discoveries (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1993), 291; Katherine Bouton, "The Nobel Pair," New York Times Magazine, January 29, 1989: 60, 82.

The First Breakthroughs

Chemist Gertrude Elion (1918 – 1999) discusses her reaction to seeing leukemia patients in remission due to her drug.

After several years of painstaking research, Elion finally developed a compound that interfered with the replication of leukemia cells. Although it was too toxic to be truly effective, it showed that she was on the right track. She continued to experiment, eventually formulating and testing over 100 purine compounds.

Finally, in 1950, Elion synthesized 6-Mercaptopurine, or 6-MP. 6-MP caused complete remissions in children with leukemia, but a relapse invariably followed. The excruciating highs and lows of watching children improve and then die drove Elion to work even harder to refine the drug. As she studied the metabolism of 6-MP over the next years, she discovered that much of it was destroyed in the body, and she was able to use that knowledge to improve the workings of the drug. When 6-MP was combined with later medications, approximately 80% of child leukemia patients would be cured; prior to 6-MP, half of all children with acute leukemia died within a few months.

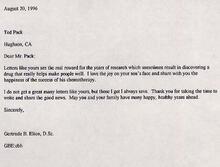

Elion was elated. "What greater joy can you have than to know what an impact your work has had on people's lives?" she asks. "We get letters from people all the time, from children who are living with leukemia. And you can't beat the feeling that you get from those children."

Notes:

- Quote beginning "What greater joy...." from Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles, and Momentous Discoveries (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1993), 295.

- Remaining information from Katherine Bouton, "The Nobel Pair," New York Times Magazine, January 29, 1989: 82; Interview with Gertrude B. Elion, March 6, 1991, Academy of Achievement, accessed February 16, 2000; available at http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/eli0int-1.

Transplants and Antivirals

Courtesy of Bella International Productions, Inc.

As Elion modified 6-MP, other researchers discovered that the drug suppressed the immune response in rabbits. Scientists had already experimented with organ transplantation, but the body's natural rejection of foreign substances had prevented success in all but identical twins, who have the same genetic structure.

In 1958, a young British surgeon used 6-MP to prevent temporarily the rejection of a transplanted kidney in a dog. Excited, Elion gave him several similar compounds, in the hopes that one would be even more effective. The following year, he used Elion's drug azathioprine (known as Imuran), to transplant a kidney successfully into a dog named Lollipop. In 1961, doctors used Imuran to perform the first successful kidney transplant between two unrelated humans. Thanks to Elion's work, organ transplantation has become routine today.

In 1968, Elion returned to an area she had first studied in the 1940s: antiviral medications. Scientists had long believed that any drug able to harm the DNA of a virus would be toxic to the surrounding healthy cells, too. Indeed, one of Elion's early compounds had shown some effectiveness against viruses but was so highly toxic that Elion put it aside in favor of her work on leukemia, transplantation, and gout. But when she heard that a similar compound had shown some antiviral properties, she returned to the subject.

After several years of work, the Burroughs Wellcome team triumphantly unveiled acyclovir (Zovirax), the first medication effective against viruses. Elion later referred to acyclovir as her "final jewel.... That such a thing was possible wasn't even imagined up until then." In 1984, the year after Elion retired, her lab developed AZT, the only drug licensed to treat AIDS in the United States until 1991. Although Elion claimed to have had little to do with AZT, her methodology had laid the groundwork for its discovery.

Notes:

- Quote beginning "final jewel...." from Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles, and Momentous Discoveries (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1993), 301.

- Remaining information from Katherine Bouton, "The Nobel Pair," New York Times Magazine, January 29, 1989: 86; Interview with Gertrude B. Elion, March 6, 1991, Academy of Achievement, accessed February 16, 2000; available at http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/eli0int-1; Emily J. Murray, ed., Notable Twentieth-Century Scientists (New York: Gale Research Inc., 1995), 584.

Growing Recognition

In this 1999 interview, Gertrude Elion discusses George Hitchings' efforts to get her into the American Society of Biological Chemists.

Over the years, Elion's career prospered. Despite some tensions in their relationship, George Hitchings proved not only an invaluable research partner but also a helpful mentor. Unlike many prominent scientists, he encouraged his assistants to write their own papers, and within two years, Elion began to publish the findings of her research; over the course of her career, she published over 225 papers. Hitchings also promoted her behind him up the ladder at Burroughs Wellcome. Eventually, Elion had a large department of assistants working for her.

Notwithstanding her achievements, Hitchings knew that Elion was still sensitive about her lack of official academic qualifications, and he hoped that membership in the distinguished American Society of Biological Chemists would be some compensation. With three strikes against her—she was a woman, had no doctorate, and was employed in industry rather than academia—her nomination appeared unlikely, but Hitchings pushed hard and was able to secure it in the early 1950s, after the publication of her twentieth article.

Elion's prestige continued to grow. In 1962, she won the American Chemical Society's Garvan Medal; in 1967, when she was named Head of Experimental Therapy, she became the first woman to lead a major research group at Burroughs Wellcome. Two years later, she received a call from George Mandell of George Washington University, who said, "[T]he kind of work you're doing, you've long since passed what a doctorate would have meant. But we've got to make an honest woman of you. We'll give you a doctorate, so we can call you 'doctor' legitimately." As she grasped her honorary degree—the first of 25 honorary doctorates, including one from Brooklyn Polytechnic —her only thought was "I wish my mother were here."

Notes:

- Quotes beginning "[T]he kind of work you're doing..." and "I wish my mother..." from Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles, and Momentous Discoveries (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1993), 298.

- Remaining information from Interview with Gertrude B. Elion, March 6, 1991, Academy of Achievement, accessed February 16, 2000; available at http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/eli0int-1.

Retirement

In 1970, needing more space and better facilities, Burroughs Wellcome moved from New York to Research Triangle Park, North Carolina. Although Elion was sad to leave the area in which she had lived her entire life, she never considered not moving with the company. She returned regularly to New York to attend her beloved Metropolitan Opera, where she retained her season subscription, but she quickly grew to love North Carolina.

In 1983, after almost four decades at Burroughs Wellcome, Elion retired from active research. She remained "about as unretired as anyone can be," however, serving as Emerita Scientist and consultant to the company, sitting on committees and editorial boards for organizations from the World Health Organization to the National Cancer Advisory Board, lecturing across the United States and abroad, and serving as research professor at Duke University. Not wanting to stop learning, she continued to attend professional meetings.

Elion also traveled widely; an adventurous globetrotter throughout her life, she had already seen most of the world, and she extended almost every professional trip she took with personal travel. A few years before she died, a relative joked that she had been everywhere except Antarctica. The following year, Elion signed up for a cruise to Antarctica.

Notes:

- Quote "about as unretired as anyone can be" from

compilation of Gertrude Elion quotes, GlaxoSmithKline Inc.

Heritage Center. - Remaining information from Sharon Bertsch McGrayne,

Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles, and

Momentous Discoveries (New York: Carol Publishing Group,

1993), 301; "The Legacy of Gertrude Elion: Inventor of

Medicines," (video), ©1999, Bella International

Productions; Katherine Bouton, "The Nobel Pair," New York

Times Magazine, January 29, 1989: 87; conversation with

Jonathan Elion, January 22, 2001.

The Nobel Prize

Courtesy of Bella International Productions, Inc.

Bella Abzug discusses international feminism at a meeting of the National Organization of Women.

Courtesy of the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University.

Courtesy of Scanpix Scandinavia.

At 6:30 am on October 17, 1988, Elion was getting dressed when a reporter called to congratulate her on winning the Nobel Prize. Startled, she retorted, "Quit your kidding. I don't think it's funny. Whoever put you up to it, I think it's a sick joke." When reporters continued to call, reality finally sank in: Elion, Hitchings, and Sir James W. Black of the University of London had indeed been awarded the Prize in Physiology or Medicine, "for their discoveries of important principles for drug treatment."

With the main body of their work having been done decades earlier, the prize came as a complete surprise. Elion knew that Hitchings had been nominated in the past, but she had no idea she herself had ever been nominated. In fact, when Hitchings and Elion were nominated as a pair, a Nobel Committee member asked why Elion was included, wondering if she had really contributed. Only when a professional friend of Elion's pointed out that Elion had been first author on many of the early papers, and that her antiviral discoveries had occurred after Hitchings retired, was the committee finally convinced.

Elion's receipt of the Nobel Prize was particularly significant, given the hurdles she had had to overcome. Few Nobels have gone to scientists working in the drug industry or those without Ph.D.s, even fewer to women; Elion was only the fifth female Nobel laureate in Medicine, the ninth in science in general.

Following the Nobel Prize, additional honors and recognitions poured in. Elion was elected to the National Academy of Science in 1990 and received the National Medal of Science, the United States' highest scientific honor, in 1991. Also in 1991, she became the first woman inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame and was elected to the National Women's Hall of Fame. The Nobel Prize made Elion even more in demand as a speaker and a spokeswoman, and her busy schedule quickly became even busier.

Notes:

- Quote beginning "Quit your kidding..." from Interview with Gertrude B. Elion, March 6, 1991, Academy of Achievement, accessed February 16, 2000; available at http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/eli0int-1.

- Remaining information from Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles, and Momentous Discoveries (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1993), 302; "Female Nobel Prize Laureates," The Nobel Prize Internet Archive, accessed January 28, 2001; available at http://www.almaz.com/nobel/women.html.

A Mentor and a Role Model

Courtesy of Bella International Productions, Inc.

Courtesy of TWIi.

Never very comfortable with scientific luminaries, Elion preferred to spend time with students. Speaking often to young people from elementary through medical school, she communicated the fun and excitement of science. "It's a wonderful life," she said. "I don't think I could have chosen anything that would have made me happier. I don't think people emphasize that enough—they think about the scientist as someone stuck away in the laboratory and oblivious to the rest of the world. That's the farthest thing from the truth. I feel as though I've made a contribution with my life." Urging her listeners not to be deterred from following their dreams, she often quoted Admiral Farragut: "Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!"

Elion acquired a widespread reputation as an inspiring, approachable, down-to-earth mentor to students, assistants, and colleagues. She encouraged her staff to explore their own ideas and made it a point never to take credit for her assistants' work; unlike most scientists, she did not put her name on papers simply because the research had been done in her lab. Always a team player, she cared far more about the outcome of the lab's collective work than about her own reputation.

Elion never felt she needed female role models and preferred to be known simply as a "scientist" rather than as a "female scientist." She was acutely aware, however, of the difficulties she had encountered because of her sex, and she recognized that the Nobel Prize put her in a unique position to smooth the way for other women. Encouraging girls to pursue scientific careers was a cause dear to her heart; she was a leader of a Glaxo Wellcome (successor to Burroughs Wellcome) program that provided mentoring and scholarships for women studying science, and when Burroughs Wellcome gave her $250,000 to contribute to a charity of her choice, she created a scholarship at Hunter College for female graduate students in chemistry.

Notes:

- Quote beginning "It's a wonderful life..." from Susan A. Ambrose, Kristin L. Dunkle, Barbara B. Lazarus, Indira Nair, and Deborah A. Harkus, Journeys of Women in Science and Engineering: No Universal Constants (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997), 140.

- Quote beginning "Damn the torpedoes!" from Interview with Gertrude B. Elion, March 6, 1991, Academy of Achievement, accessed February 16, 2000; available at http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/eli0int-1.

- Remaining information from conversation with Jonathan Elion, January 22, 2001; Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles, and Momentous Discoveries (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1993), 303.

A True Humanitarian

Courtesy of TWIi.

Gertrude Elion discusses the importance of letters sent to her from patients helped by her medications.

Courtesy of Bella International Productions, Inc.

Elion was a true humanitarian as well as an outstanding scientist. Although she respected those who did science for science's own sake, she always kept in mind the patients whose diseases she aimed to cure and focused on the practical applications of her research. The personal tragedies she had experienced and the contact she had with patients kept the goal of curing people squarely in front of her.

Far more than she did the Nobel Prize, Elion treasured the knowledge that her work had directly benefited the lives of countless individuals. "[Y]ou can't beat the feeling that you get from those children," she said. "[W]hen the Nobel Prize came in, everybody said, 'How does it feel to get the Nobel Prize?' And I said, 'It's very nice but that's not what it's all about.' I'm not belittling the prize. The prize has done a lot for me, but if it hadn't happened, it wouldn't have made that much difference.... When you meet someone who has lived for twenty-five years with a kidney graft, there's your reward."

Elion had a great love of life and a warm personality that infected everyone around her. Those who knew her unanimously emphasize—even more than her scientific achievements—how much she cared about people, from her family and friends, to those who took her drugs, to the nameless masses who might someday benefit from her research. When it was discovered that one of her drugs was an effective treatment for Leshmaniasis disease, a serious problem in South America, she pushed hard for Burroughs Wellcome to follow up on the matter, regardless of the money involved. As a former colleague remarked, "She has a real social conscience.... In fifty years, Trudy Elion will have done more cumulatively for the human condition than Mother Theresa."

Notes:

- Quote beginning "[Y]ou can't beat the feeling..." from Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles, and Momentous Discoveries (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1993), 295-297.

- Quote beginning "She has a real social conscience..." from Tom Krenitsky, cited in McGrayne, 297-298.

- Remaining information from McGrayne, 297.

Legacy

Gertrude Elion was an enormously productive and successful chemist. In addition to treatments for leukemia, the herpes virus, gout, and immunity disorders, she also helped to develop medications for arthritis, malaria, and bacterial infections, among other diseases. At a time when biochemical knowledge was far more limited than it is today and when many of our current sophisticated scientific instruments had yet to be invented, she and Hitchings were able to create remedies for some terrible medical problems.

Elion and Hitchings' revolutionary approach to drug development, based on an understanding of the chemical composition of disease and healthy cells and the differences between them, has become standard in pharmaceutical research. In years to come, scientists will be able to use their methods in search of cures for the world's remaining scourges, including the cancer Elion had always hoped to vanquish.

When Elion died on February 21, 1999, the head of Glaxo Wellcome observed astutely, "Gertrude Elion's love of science was surpassed only by her compassion for people." Her generous heart and brilliant mind touched countless individuals around the world. In the drugs she developed, the scientists she influenced, and the young people she inspired, she left a legacy that will benefit humanity for years to come.

Notes:

- Quote beginning "Gertrude Elion's love of science...." from Glaxo Wellcome Press Release at Elion's death, February 22, 1999, accessed April 4, 2000 from http://www.invent.org/pr22299.html

Media

Timeline

Gertrude Belle Elion >born in New York City to Bertha (Cohen) and Robert Elion, on January 23

Grandfather dies painfully of stomach cancer, inspiring Elion to pursue a career in science

Graduates summa cum laude from Hunter College, in New York

Applies to 15 graduate schools but, because of gender discrimination, is turned down by all for graduate assistantships

Unable to find research job, volunteers in chemistry lab

Receives M.S. in Chemistry from New York University

Fiancé Leonard Canter dies of a bacterial infection, a few years before penicillin becomes readily available

Shortage of male scientists due to World War II enables Elion to find job as food chemistry analyst

Begins working for George Hitchings at Burroughs Wellcome Co., a pharmaceutical company

Synthesizes 6-Mercaptopurine (Purinethol), which cures childhood leukemia when used with later-developed medicines

Opens field of organ transplantation when the immunosuppressant Imuran, which she developed, is used to transplant a foreign kidney into Lollipop, a German shepherd

Becomes first woman to lead a major research group at Burroughs Wellcome when named Head of Experimental Therapy

Receives honorary doctorate from George Washington University, the first of 25 honorary degrees

Moves to North Carolina when Burroughs Wellcome relocates

Elion's lab develops acyclovir (Zovirax), the first medicine to treat viral infections

Retires from Burroughs Wellcome but remains as Emerita Scientist and consultant

Elion's lab uses her methodology to develop AZT, until 1991 the only drug licensed in the United States to treat AIDS

Shares Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with George Hitchings, for development of rational method for drug design and discoveries in the principles of chemotherapy

Elected to the National Academy of Sciences

Receives the National Medal of Science, the United States' highest scientific honor

Becomes first woman inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame

Dies on February 21, in Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Bibliography

Published Sources

Altman, Lawrence K. "Gertrude Elion, Drug Developer, Dies at 81." New York Times, February 23, 1999, accessed March 3, 2000; available from http://www.wellesley.edu/Chemistry/chem227/news/obit-elion.html.

Ambrose, Susan A., Kristin L. Dunkle, Barbara B. Lazarus, Indira Nair, and Deborah A. Harkus. Journeys of Women in Science and Engineering: No Universal Constants. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997.

Bailey, Martha J. American Women in Science: A Biographical Dictionary. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 1994.

Bouton, Katherine. "The Nobel Pair." New York Times Magazine, January 29, 1989, 28+.

Brokaw, Tom. The Greatest Generation. New York: Random House, 1998.

Cawthon, Frances. "The science of perseverance: Nobel winner Elion inducted into Women's Hall of Fame." Atlanta Journal and Constitution, November 18, 1991, sec F, 1.

Colburn, Don. "Pathway to the Prize: Gertrude Elion, From Unpaid Lab Assistant to Nobel Glory." Washington Post, October 25, 1988, sec Z, 10.

"Female Nobel Prize Laureates." The Nobel Prize Internet Archive, accessed January 28, 2001; available at http://www.almaz.com/nobel/women.html.

"Gertrude B. Elion." Autobiography, Nobel Foundation, accessed February 16, 2000; available at http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1988/elion-autobio.html (updated from earlier page address).

"Gertrude B. Elion, Nobel Prize in Medicine." Biography, Academy of Achievement, accessed February 16, 2000; available at http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/eli0bio-1.

"Gertrude B. Elion, Nobel Prize in Medicine." Interview March 6, 1991, Academy of Achievement, accessed February 16, 2000; available at http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/eli0int-1.

"Gertrude B. Elion, Inventure Minute." Audio from the National Inventors Hall of Fame, accessed August 13, 2007 from http://www.invent.org/m14.4/elion.ra.

"Gertrude Belle Elion." National Inventors Hall of Fame, accessed August 13, 2007; available from http://www.invent.org/hall_of_fame/51.html.

"Gertrude Belle Elion (1918–1999). Anti-cancer and other lifesaving drugs." Lemelson-MIT Program's Invention Dimension, accessed August 13, 2007 from http://web.mit.edu/invent/iow/elion2.html.

"Gertrude Elion Memorial." (Video), March 27, 1999, GlaxoSmithKline Inc. Heritage Center.

Goodman, Miles. "Gertrude Belle Elion (1918- )." In Women in Chemistry and Physics: A Biobibliographic Sourcebook, ed. Louise S. Grinstein, et.al. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1993, 169-172.

Holloway, Marguerite. "The satisfaction of delayed gratification." Scientific American, October 1991, 40+.

"The Legacy of Gertrude Elion: Inventor of Medicines." (Video.) ©1999, Bella International Productions, Inc.

McGrayne, Sharon Bertsch. Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles, and Momentous Discoveries. New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1993.

Murray, Emily J., ed. Notable Twentieth-Century Scientists. New York: Gale Research Inc., 1995.

Parrish, Marilyn McKinley. "Gertrude Belle Elion (1918- ), Biochemist." In Notable Women in the Physical Sciences: A Biographical Dictionary, ed. Benjamin F. Shearer and Barbara Shearer. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1997, 85-87.

"A Science Odyssey: People and Discoveries: Drugs developed for leukemia." Accessed March 30, 2000; available at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aso/databank/entries/dm50le.html.

Slater, Elinor, and Robert Slater. Great Jewish Women. Middle Village, NY: Jonathan David Publishers, 1994.

"Women in Science." Scientific American, April 27, 1998, accessed August 13, 2007; available at http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?articleID=000B5E8B-C6B4-1CE1-8583809EC5880000&sc=I100322.

Archival Sources

GlaxoSmithKline Inc. Heritage Center: Company newsletters, reports, photographs, etc. relating to Gertrude B. Elion's career at Burroughs Wellcome and Glaxo Wellcome.

Estate of Gertrude B. Elion, currently housed by GlaxoSmithKline Inc. Heritage Center: Correspondence, publications, professional papers, photographs, etc. relating to Gertrude B. Elion's life and career.

Wow

Elion completely changed the face of medicine. Such a beautifu; soul. Her efforts shall not go unrecognized.

My chemical engineer wife instantly responded "penicillin" and "polio vaccine" when I said the names "Fleming" and "Salk". Elion, who did more than both combined, she had never heard of. Why?