Sarah Gettleman Silberman

On June 19, 2008, several hundred people gathered at Montgomery College in Rockville, MD, to celebrate the life of the late Sarah Silberman. She had been a student there in sculpture and ceramics since 1981 and was much loved and admired by faculty members and her fellow students. In October 2004 when she was 94 she was honored with a one-person show of her life's work in the college art gallery, the only one-person show there has ever been for a student. Later there were awards and an honorary degree, and in her last public appearance before she passed away, she was honored at the reopening of the art gallery, which had been renamed for her and refurbished and expanded with funds she had donated for that purpose and for scholarships.

I first met Sarah in 1994 in Kevin Hluth's ceramics class. I was struggling with my own work, so I didn't pay much attention to this tiny little old lady. Then came a student show, and she brought in her Bust of Henry Lofton, a twice life-size study of an 11-year-old African American boy. That's all I had to see to know that I was sharing a studio with an exceptional talent.

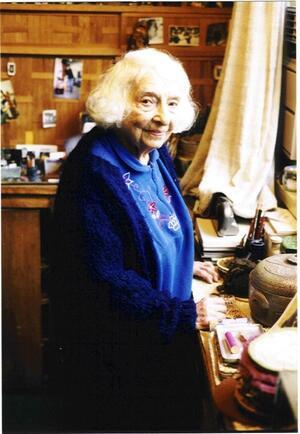

I heard from other students about her house and her collection, and I asked if I could photograph it. Several years later, she said "yes." When I arrived with my camera, she took me through all of the rooms, picking up a piece here and there and telling me its history. Every piece had its own story. She loved the first batch of pictures, and we bonded.

In the art department, we used the pictures to select works for Sarah's one-person show in 2004 and the buzz from the show led to the opportunity to do a book on her life, The Genius of Sarah Silberman, a Lifetime Student of Sculpture. Everyone at the college who knew Sarah wanted there to be a book, but none of us knew much about her life before 1981 when she started attending classes. From her stories, I was able to piece together her family history and her artistic development at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the Corcoran, and with a series of private teachers. I say "piece together" because Sarah said she had no sense of time and I think she was right about that.

Sarah's father was a furrier in Odessa in Czarist Russia before they emigrated in 1913, first to Brazil and then to the United States. It's much like the story of many immigrant families – after many hardships, the Gettlemans became successful furriers in Atlantic City and were able to give their children every advantage. There were summer vacations in New Hampshire and trips to Europe; there were horses to ride and Sarah and her sisters took piano lessons and played in local concerts.

In 1927 before her last year of high school, she took a resident summer course at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA). Albert Laessle persuaded her to join his sculpture class and from then on sculpture became her life. In 1931 she won the Cresson Scholarship, which allowed her three months travel in Europe and required her to visit at least 22 museums. Her new husband, Dave Silberman, whom she had married without telling her parents, went with her. Later she said Dave remembered everything they had seen, but to her it was all a blur.

From 1933 to 1941 she and Dave lived in Atlantic City. She worked in a studio at home and for a time in a studio on Pine Street in Philadelphia, where she did a two-thirds life-size sculpture of Joe Brown, who had been Mr. America. She continued to play in concerts and recitals with her two sisters and she had her two sons, Dave and Bill. In 1941, the family moved to Washington where her husband became a partner in Jandel Furs.

The first thing Sarah did was enroll at the Corcoran Art School. She was there for four years and was a student first of Robert Laurent and then of Heinz Warneke. Both of these artists are known for their works in wood and Sarah must have learned a lot from them because most of her works in wood date from this period and later. It's quite likely that Heinz Warneke actually learned plaster casting from Sarah. She had developed incredible skills in this medium at PAFA, and Warneke is not known to have done anything in plaster until about the time Sarah was his student. She told me that she had to help him out in class because he barely spoke English at that time and, since she knew "Jewish," she could translate his German for the other students.

She exhibited her work at museums and galleries in Washington and Baltimore, and at some point she had a studio on 7th Street near the old Hecht Co. department store, where she did the Bust of Henry Lofton. She taught sculpture at the Thai Legation and arts and crafts at Walter Reed to wounded military personnel.

In 1950 she bought a piece of land in Silver Spring to build a studio and eventually a house. That story needs to be told by one of her sons, because they were her labor force. It was Sarah, two teenage boys, and a do-it-yourself book. They did everything from pouring concrete and laying the copper tubing for radiant heating to raising the walls to roofing, wiring and plumbing. For some reason, it was just at this time that Sarah seems to have dropped all efforts to promote herself as a sculptor. She told me that she had never wanted to do anything but her work, and that she had never been interested in sales or the self-promotion that is essential to commercial success as an artist. If that wasn't always true, it certainly was after 1950.

What one sees in her later work is a continuation of her work as a portraitist and the ever recurring theme of mother and child. Most of the heads still standing around Sarah's studio represented friendships, sometimes long, sometimes intense and sometimes both. She loved this work, and it was almost as if the models were really there with her: her mother, her sisters, her husband Dave, her sons, and a host of close friends, and, of course, Henry Lofton. In the mother and child pieces one finds the essentials of Sarah's character and her deepest feelings. If there is one word to describe Sarah, it is "Mother." It's everywhere in her work and it's there in the extraordinary relationship she had with her sons, who preferred working on the house with her to all those other things that boys do. This theme was consistent in her work from her days at PAFA right through into the 1980s and 1990s.

Sarah lost her husband Dave, the love of her life, to a heart attack in November 1978, but she had many friends and a loving family, and by 1981 she was ready for a new chapter in her life. All of her training and experience were brought to bear on a whole new body of work, both naturalistic and abstract and in a great variety of materials. She never had much to say about artistic theories or styles or trends. Her focus was always on her materials, her tools, and her own vision of what she intended to create. What you see in her work is who she was because it all came from within.

I have a painting by this artist and was curious about the authenticity of it