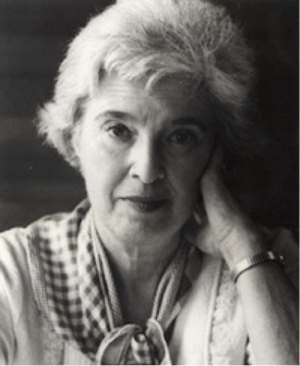

Gerda Lerner

Gerda Lerner's life and work so inextricably intertwined, gained prominence thanks to her fearless, continual examination of the world.

"In our culture, and in most patriarchal cultures, we have made an artificial division between thinking and acting, as though the two were mutually exclusive," she said in a 2002 interview with the Wisconsin Academy Review. "The most important thing, the thing I have always lived by, is that you must be engaged in some way in the world in which you live. How, is for each person to choose."

Gerda Kronstein was born in Vienna, Austria on April 30, 1920. Raised in an upper-middle-class Jewish family, she developed a strong sense of justice at an early age, as she noticed the unequal treatment of household servants. But her lens on the world changed dramatically when the Nazi regime imprisoned her family.

As she recounted 63 years later in Fireweed: A Political Autobiography, the "fragile community of survival" she developed with her cellmates taught her that "if you wanted to survive you could not do it alone and you had to fight with all your strength to keep some sort of social contract… These hours, days, weeks and months in jail were the most important events of my life: they gave it a meaning and a shape I have ever since tried to comprehend."

Lerner's life experience equipped her to resist conformity — in particular, questioning the societal norms insisting that women had no history.

"Having lived through the transition from being an accepted and rather privileged member of society and from one day to the next being a total outcast and victim, I learned something about how society can manipulate people," she said in 2002. "I applied that to understanding how it was possible to manipulate half the people of the world to accept that they are inferior."

After emigrating to the United States as a refugee, she ended up in New York and settled into a happy marriage with filmmaker Carl Lerner. An activist in grassroots social and political movements, her projects included co-writing the screenplay for "Black Like Me," directed by her husband.

Only at age 38, when her children were older, did she begin college. She received her BA from the New School for Social Research in 1963 and went on to complete an MA and Ph.D. from Columbia University in an astonishing three years, finishing in 1966.

Just getting women's history recognized as a discipline was difficult enough. At Columbia, she found deep resistance to her studies of women's history, not yet considered a scholarly field. Even at Sarah Lawrence College, predominantly a women's college, she faced resistance to the idea of a course in women's history.

Lerner's nuanced understanding of women's history eschewed simple reverence for influential women in favor of a rigorous exploration of women's lives.

The first generation of women's historians had an urgency, a political aim, to recover the voices of women whose contributions had been lost.

Lerner's work paved the way for other subfields of study that had struggled for respect. As editor of the groundbreaking 1972 book Black Women in White America: A Documentary History, she had a profound impact on the development of Black Women's Studies.

In 1972, the field had progressed enough for Lerner to found the nation's first master's degree in women's history. In 1980, following her husband's death, she moved to University of Wisconsin-Madison to establish a doctoral program.

Lerner often spoke passionately about the cost of being a pioneer — the only one, the first one, a minority.

Lerner's tenacity earned her a reputation for antagonizing students and colleagues. To some, though, that weakness was also her great strength. Her willingness to be disliked made the road smoother for those who followed.

Vigorously active well into her 70s, the force of her personality often overruled hesitation as she brought others into her world. More often than not, this involved the outdoors.

Though Lerner spent many of her retirement years teaching in her winter home of North Carolina, near family, she had carved out a life in Madison. At her home in Oakwood Village, a retirement community home to many retired academics, she continued to teach, fight and revel in the experience of living. She led her peers in discussions on aging, empowering them even as they needed more assistance.

"Old age is not a contagious disease," she wrote, at age 89, in her 2009 book Living With History/Making Social Change. "It is the ripening of the fruit, the preparation for the harshness of winter, when the roots grow and strengthen."

Adapted from University of Wisconsin-Madison News, January 4, 2013