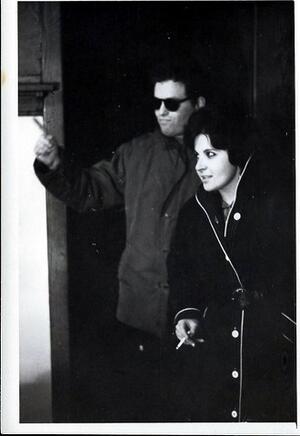

Roberta Galler

As a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) staff member, Roberta Galler was among hundreds arrested in Jackson, Mississippi in June 1965 protesting local attempts to subvert implementation of the new Voting Rights Act. After being thrown into the Hinds County Jail, Roberta first encountered the Jackson Jewish community in the form of Rabbi Perry Nussbaum. A quiet civil rights supporter against his congregation’s wishes, Nussbaum came into the cell housing Roberta and several other Jewish women. Holding up toothbrushes, soap, and other small necessities, he said, "Okay, who in here are my people?" Roberta stepped forward and said "Either all of us are your people or none of us are your people."

I smiled inwardly thinking of Roberta’s defiance and Jewish universalism as I sat on a panel at Rabbi Nussbaum’s temple forty nine years later, the same one bombed by the Ku Klux Klan in 1967. We were there to honor Jewish Freedom Summer volunteers as part of the 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer events. I want to honor Roberta, who died on February 12.

Many historians and activists, including Rita Schwerner Bender, are casting a jaundiced eye at these 50th anniversary celebrations because they obscure the daily work and decades-long project of movement building. Like most of the women I profiled in my book, Going South: Jewish Women in the Civil Rights Movement, Roberta did the daily, behind the scenes tasks that built and sustained the infrastructure of one of our country’s most remarkable movements for expanding democracy. She did not seek recognition for her many contributions, but she knew their worth.

Roberta Galler began her civil rights activism in the North, coming to Jackson after Freedom Summer in 1964 at the request of Lawrence Guyot. He wanted Roberta to travel the state, helping to organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP)’s Congressional Challenge. Because those elected to Congress from Mississippi did not reflect the votes of the state’s disenfranchised majority Black population, the MFDP challenged the election’s legitimacy. Roberta recalled that when she traveled around the state, she also cooked food to feed people, throwing what she called “Jewish soul food parties.”

Born into a working-class Jewish family in Chicago, Roberta had polio as a child. During childhood visits to Warm Springs, Georgia (where FDR sought treatment and made it possible for many others to do so), she awakened to racism. When she looked around, she noticed that the only Black people there were servants, not patients. She began to ask why, and that became one of the foundations of her remarkable empathy.

Determined not to be limited by her disability, Roberta, after a brief stay at a Dickensian “School for Crippled Children,” managed to attend a regular school relying on crutches. She relished telling me how, as a young woman, she put her body at the front of the line during demonstrations to taunt the notorious Chicago police. On leave from studying journalism on scholarship at Northwestern University, Roberta managed the journal New University Thought, which chronicled the southern civil rights movement for northern students. Upon hearing the testimonies of southern activists in 1962, Roberta said she simply “forgot to return to school” and committed herself fully to the movement.

As head of Chicago Friends of SNCC, Roberta kept in close touch with SNCC field offices on a daily basis, bringing food, money, media attention, and personal support to southern activists. In one moment of crisis, when beloved NAACP activist Medgar Evers was murdered in his own driveway on June 11, 1963, Roberta spoke repeatedly by phone to a young local SNCC activist, Willie Peacock. With Byron de la Beckwith openly boasting about what he had done, Peacock did not trust himself to stay with the ethic of nonviolence. Thirty years later, Beckwith was re-tried and convicted for the murder of Medgar Evers. Roberta Galler’s caring work—hosting the young activist Jimmy Travis after he was shot in 1963 and bearing witness to Willie Peacock’s despair and rage—is invisible to history. But such work sustained the movement’s foot soldiers and protected SNCC’s “beloved community.”

Roberta went South just as Black Power concepts were gaining ascendancy. She was very honest about how long it took her to understand that even though she was very Black-identified, she could not justify staying in Mississippi after SNCC voted to become an all-Black organization. As Roberta recalled, “We did not leave the Movement; we just had to leave the South.” She worked in anti-poverty programs in Chicago and became the first administrator for New York’s Center for Constitutional Rights. She later returned to school and established a psychotherapy practice in Greenwich Village.

Roberta Galler’s last home was a wheelchair-accessible apartment in Battery Park City in downtown Manhattan. On September 11, 2001, planes flew into the nearby World Trade Center. It must have taken incredible grit for her to evacuate by riding up the West Side Highway in her wheelchair. Picturing Roberta making her own way under such extraordinary circumstances makes me all the more grateful for the work she did to create safety for the movement and the people she loved.

I went to grammar school it’s roberta and haven’t seen her in probably since than, I remember her as a caring and thoughtful girl. We had party’s at her house and although she had polio, it never affected her participating and never once did I ever hear her complain. I was just sitting at home when her name popped into my mind. I googled it and glad i did. What ever reason that happened is a question I don’t have an answer to.

If she was still here i would congratulate her for being a great American and pratiot in not letting anything stop her from completing her goals.

That’s about it, excpept i too was born in 1936 and I do remember celebrating birthdays at her house. May she rest in peace and bless her for the time that she was here and accomplished, Sincerely, Bob Reisman