Working and Striking

Introduction

As you read through the documents, keep these general questions in mind:

- What makes a person independent?

- What words or phrases do the authors/narrators use to describe their identities as workers?

- How do the workers in these texts form their American Jewish identities? Point to specific examples.

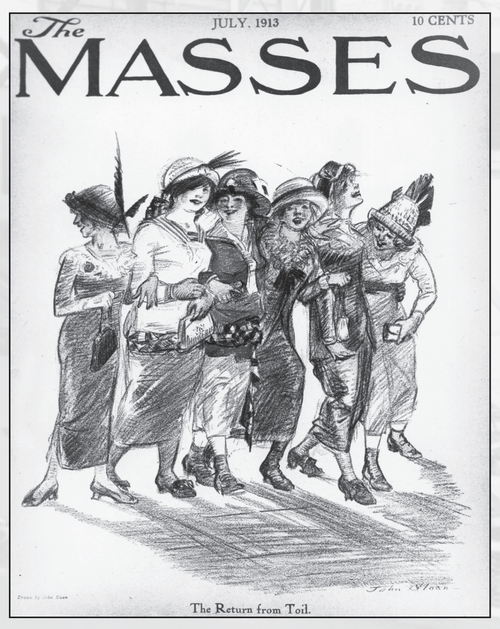

"The Return from Toil," July 1913

Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.

Discussion Questions

- What do you see in this image that might tell you something about what work life offered young urban girls in the early 20th century?

- Does anything about this image surprise you?

- How do you understand the juxtaposition between the word “toil” in the title and what is depicted here?

Sarah Rozner recalls "testing" her mother

The three of us were striking, my brother Dave, my sister Fanny, and me. Fanny was 15 and she’d be on the corner selling papers for the strike. She had a good time; she was young and gay and singing. My brother’s first wife was my girlfriend, and we had one good skirt between us. If she went on the picket line, we raised the hem, because she was much shorter than I; when I went on the picket line, I’d let the hem down. That’s the way we lived.

Fanny got a couple of pennies from selling the socialist papers, enough for a couple of loaves of bread. But we were hungry. They didn’t feed us in the strike hall. Sedosky, a Jewish writer, had a restaurant where for 15 cents they used to get some strike tickets for a full meal. But that was only for single men. They finally did give us some tickets to a storehouse. It was on Maxwell or Jefferson Street and was a storehouse for strikers who had family responsibilities. They had food of various sorts: bread, herring, beans, rice. None of the family wanted to go there, so I went alone. I brought home the “bacon.”

I was already filled up with revolution, and had no intention of going back to work as a scab, but I wanted to test my mother. I said, “I think I’m going back to work. What the hell, we don’t want to starve. But before I do that, you come with me to the meeting.” We walked I don’t know how many miles to Hod Carriers Hall, which was at Addison and Central. My mother listened to the speeches. They were in Jewish, Polish, Lithuanian. In English, there was very little… There was a Jewish orator who spoke from his heart. He touched anyone who had feeling. After the meeting I said to my mother, “Now I’m going back to the shop.” She said, “Over my dead body.”

Discussion Questions

- What does Sarah get out of being on strike?

- What strikes you about the story of Sarah and her friend wearing the same skirt to walk the picket line?

- Why do you think Sarah decides to “test” her mother? What happens to Sarah’s mother after hearing speeches by Union organizers?

Rose Schneiderman describes the strength of girls and women

Women have proved in the late strike that they can be faithful to an organization and to each other. The men give us the credit of winning the strike. Certainly our organization constantly grows stronger, and the Woman's Trade Union League makes progress. The girls and women by their meetings and discussions come to understand and sympathize with each other, and more and more easily they act together. It is the only way in which they can hope to hold what they now have or better present conditions. Certainly there is no hope from the mercy of the bosses. Each boss does the best he can for himself with no thought of the other bosses, and that compels each to gouge and squeeze his hands to the last penny in order to make a profit. So we must stand together to resist, for we will get what we can take, just that and no more.

Discussion Question

What changes does Schneiderman notice occurring among the shop girls after their strike? To what does she credit these changes?