Wednesdays in Mississippi Documents

Wednesdays in Mississippi - Excerpts from the Report from Polly Cowan, Project Coordinator, 1964

Wednesdays in Mississippi - Excerpts from the Report from Polly Cowan, Project Coordinator, 1964

How the project was conceived

An inter-racial team of four women went to Selma, Alabama last October, 1963 – 4th and 5th. They went because of their concern for women and girls in the hands of the police and to verify the reports of mistreatment in the Dallas County jails. Many teen-agers and their parents spoke to members of the team during those two days.

One of the team members was Miss Dorothy I. Height, National President of the National Council of Negro Women. Miss Height, who is also on the staff of the National Board of the YWCA, transmitted her concern to the YWCA when she returned from Alabama.

The National Board of the YWCA was able to enlist the interest and support of the National Council of Jewish Women, the National Council of Catholic Women and the United Church Women. These groups and the National Council of Negro Women formed a base of operation to act on their common concern.

...

Purpose

Our original purpose was to build a bridge between the Negro and white women of the south. The mechanism through which we planned to work was those national women’s organizations which involved women of both races whose goals include the active pursuit of human and civil rights.

As the project progressed, even before the Wednesday visits began, we realized that this process of working with the southern women in order to open their eyes, their hearts and their minds, would also cause the northern women to re-examine and re-valuate themselves in their northern world. We also realized that the exposure of northern women to the effect of life behind the cotton curtain would be a cultural shock. The visits have proved that we were right. Our team members are working out their involvement in dimensions which would be impossible to estimate. The ripples will continue long after the waves have subsided.

Transcript of excerpts from Polly Cowan, "Wednesdays in Mississippi - Report from Polly Cowan, Project Coordinator," 1964. Wednesdays in Mississippi: Civil Rights as Women's Work exhibit website.

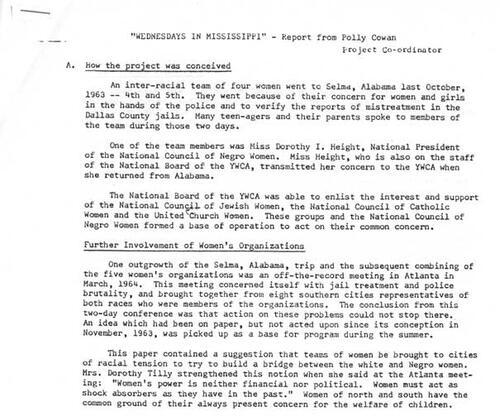

Polly Cowan's Report on Wednesdays from Mississippi, 1964, page 1

"Wednesdays in Mississippi - Report from Polly Cowan, Project Coordinator," 1964, page 1. Wednesdays in Mississippi: Civil Rights as Women's Work exhibit website. (See The Creation: Beginning: The Call for Action: The Start)

Courtesy of the National Park Service/Mary McLeod Bethune Council House.

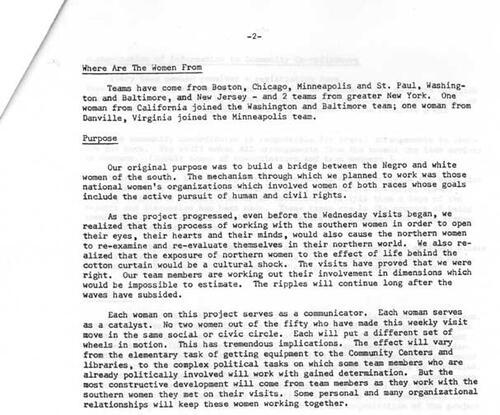

Polly Cowan's Report on Wednesdays from Mississippi, 1964, page 2

"Wednesdays in Mississippi - Report from Polly Cowan, Project Coordinator," 1964, page 2. Wednesdays in Mississippi: Civil Rights as Women's Work exhibit website. (See The Creation: Goals: "Wednesdays in Mississippi" by Polly Cowan)

Courtesy of the National Park Service/Mary McLeod Bethune Council House.

Excerpts from Dorothy Height Oral History

Well, Polly [Cowan] knew of the work we were doing with some of the Head Start people down in Mississippi…She wrote a little note back to me, and she said – because by this time things were heating up in Mississippi. Bob Moses had decided that though he was a successful teacher, he would go down there and organize Freedom Schools. So she wrote and she said, ‘The word is out that all of those young people going from Ivy League colleges are communists.’* And she said, ‘My children are going, and I know there are other women who’d want to kind of be there to support their children and to let it be known that we are responsible people.’

She said, ‘I think if we could get the Cadillac crowd to do something I would call Wednesdays in Mississippi, that they would prepare and go in on Tuesday, that they would give some kind of a service.’ She said, ‘We don’t want them to go as sightseers. They have to be willing to do something that furthers the movement.’ And then we would somehow find a way to get together and then come out on Thursdays and go home, each one committed to doing something about civil rights back in their community, but also helping to expose the conditions that are affecting people in Mississippi…

Then we made a list of women that we thought of who would be very good. We began to think of women who had skills, who could do something. Augusta Baker, who was a librarian at the county library, we said, ‘She’s a good storyteller. We would have her.’ We thought of women like [Ellen] Terry, said if we had her, she’s a poet and she writes, and the like…

*In this context, “communist” was meant as a derogatory term. It was also sometimes used as a shorthand way to imply “Jewish” (due to the association of Jews and radicalism in the early 20th century).

Dorothy Height, interviewed by Holly Cowan Shulman for "Wednesdays in Mississippi: Civil Rights as Women's Work.” 16 October 2002. Permission to use granted by Holly C. Shulman.

Excerpt from Sylvia Weinberg Radov Oral History

The original purpose [of WIMS], as I understood it, was to give a sense of legitimacy to these college kids, to our kids, not mine, but it was a pretty close neighborhood. Those were our kids. And come down to Mississippi, a bunch of lovely ladies of all colors and ages, and to come dressed like ladies and behave like ladies, which we didn’t ordinarily—we spent a lot of time in blue jeans—and show the kids that we cared, and to live in the community and show the community that we were nice ladies with good backgrounds and good thoughts, a good education, and we were to scout out our own place to fit into this. It sounded like a great idea to me.…I felt it was the right thing to do. First of all, I did have a real connection and a real sympathy and interest in what the college kids were doing that year. I really did. And if this was some help to them—and it was presented originally more as a backup for the kids, and there’s no reason—for the same reason if one of the kids in the neighborhood fell off his bike in front of your house, you picked him up and brushed him off. That was the same thing. But of course, it developed to be much more…

Well, we met down at the airport, and we took a plane together, and Doris met us with a car and dropped us off where we were supposed to be. I don’t know, I was insecure. I could find my way around Paris and I could get along very fine in London, but I wasn’t real sure about what I could do in Jackson, Mississippi, and she was our shepherd…

I’m trying to think what else [we did]. Mostly we ate in each other’s homes. We didn’t go out for fancy meals at a restaurant, and we did not take on the right to sit at the same soda fountain kind of a thing. That’s not what we were after. That was an issue at the time, too… Polly’s eyes were way above a shared soda. Am I right? And her eyes were to support the kids and to help guarantee the right to vote and to live where you wanted to live. I think that’s about as much as we could handle. That’s a big bite at that time. It doesn’t sound like anything now.

Sylvia Weinberg Radov, interviewed by Amy Murrell, Chicago, Illinois, 25 June 2002. Permission to use granted by Holly C. Shulman.

Excerpt from Oral History with Beatrice "Buddy" Cummings Mayer

First of all, I thought that Wednesdays was a very brave, innovative moral thrust into the human neglect and abuse of civil rights violations. It was the most innovative and total participatory attack on civil rights abuses from a community approach that had so differed from the politician’s approach. This, I thought, was a people-to-people approach; and that, I thought, was how it was so different and so appropriate, so unique to work with the people most effective very much on a one-to-one basis as opposed through any of the existing political processes starting with the president down and going to all of the different national organizations that had some sort of a political base. This was not a political base. It was nonpartisan, and it was really, I think, from heart to heart and from mind to heart… I think the civil rights movement would have been incomplete if present and future generations only thought of it as a political process led by political leaders, and that individuals like myself didn’t have an opportunity to both express their concerns and to participate in trying to build bridges.”

Beatrice “Buddy” Mayer, interviewed by Holly Cowan Shulman, Chicago, Illinois, 25 June 2002. Permission to use granted by Holly C. Shulman.