Reflections and images - Jewish attitudes toward the Civil Rights Movement

Document Discussion Guide

Read each text out loud to your group. For each text, discuss and answer the following questions:

- Who wrote this text? When? For what purpose and what audience?

- Based on this document, how did this person (or these people) feel about civil rights?

- Why do you think this person (or these people) felt that way?

- What aspects of his/her/their identity do you think motivated him/her/them?

- What experiences do you think motivated him/her/them?

- What does this person (or these people) have to say about Jews' relationship to the Civil Rights Movement?

For any photographs in your packet, spend some time looking closely at the image. Then discuss and answer the following questions:

- What's going on in this photograph?

- What do you see that makes you say that?

- What is your gut reaction or emotional response to this photo?

- What about this photograph makes you feel that way?

- If you were a Jew considering getting involved in the Civil Rights Movement, how might a scene like this influence your decision?

- Who do you think took this photograph, and for what purpose and audience?

After examining and discussing all the documents in your packet, fill in the following lists:

| Some Reasons Why Jews Supported Civil Rights | Some Reasons Why Jews Didn't Support Civil Rights |

|---|---|

| Things that made civil rights or being involved in the Civil Rights Movement complicated for Jews |

|---|

"Stayed on Freedom" excerpt

Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, "Stayed on Freedom: Jews in the Civil Rights Movement and After," in The Narrow Bridge: Jewish Views on Multiculturalism, edited by Marla Brettschneider (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996), 106, 111-112.

An Orphan in History excerpt, pp. 50-53

Paul Cowan was a young civil rights activist in the 1960s and 1970s. His mother Polly Cowan was also a civil rights activist, helping to found Wednesdays in Mississippi, an organization composed of middle-class, middle-aged Northern and Southern women who met in Mississippi to support civil rights work, to learn more about the situation in the south, and to keep an eye on younger activists like her son. In An Orphan in History: Retrieving a Jewish Legacy, Paul Cowan shares some of the Jewish values he inherited from his mother and some of his own experiences in the Civil Rights Movement.

She was too much of an egalitarian to admit she subscribed to the religious idea that the Jews were a chosen people. Yet the subtext of her words carried that message. We were chosen to suffer; chosen to achieve brilliance; chosen to wage a ceaseless war for social justice. Indeed, to her, the struggle for justice was nothing less than a commandment, even though she had no interest at all in the concept of halacha – the intricate system of laws that have bound the Jewish nation together for five thousand years. I don’t think she could imagine living without fighting for the oppressed.…

As I recall her now – with her dazzling smile, her well-cared for, slender body – I think of three separate episodes which suggest the power and the limitation of the kind of Jewishness she tried so hard to instill in me.

In 1964, I was at Oxford, Ohio, training to do civil-rights work in Mississippi. Early one evening we heard that three integrationists, two whites named Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman and a black named James Chaney, were missing in a rural Mississippi town, probably killed by the Ku Klux Klan. It was headline news all over America. We were all terrified – and so were our parents. Late that evening I walked by a phone booth and heard a girl yell at her mother, “Of course I’m still going to go there. If someone in Nazi Germany had done what we’re doing, your brother would still be alive today.” I realized I would never have to say anything like that to my mother. For the earnest, eager cry I had overheard summed up everything I had learned about Judaism since childhood.

A month later Polly and Dorothy Height, president of the National Council of Negro Women, were on a mission to Mississippi, as part of Wednesdays in Mississippi, an effort my mother had conceived to bring black and white women together. Quite casually, they had decided to integrate a motel near Jackson. At about 8 p.m., Rachel and I went over to visit them. We noticed some white teenagers drinking beer by the motel pool, muttering racist comments. Polly and Miss Height seemed completely unworried.

After my parents died, Dorothy Height told me that a cross had been burned in front of their window late that night. She and Polly doubted they would survive until the next morning. Polly, who talked about her past, her feelings, her work, even her sexual attitudes with complete freedom, had never bothered to mention that part of the episode. Why should she dwell on something that might make her seem heroic? She knew that the people in whose name she was acting—Jews in Hitler’s Europe, blacks in the South—had faced far greater dangers than she ever would. Many millions had died. In her mind, where good manners and good taste were inextricably interwoven with progressive politics, it seemed unseemly to dwell on the few minutes of fear she had faced.

Excerpts are from Cowan, Paul. An Orphan in History: One Man's Triumphant Search for His Jewish Roots (Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2002). Permission granted by Jewish Lights Publishing, www.jewishlights.com.

This I Believe - Justine Wise Polier

Justine Wise Polier, the daughter of Rabbi Stephen Wise, worked on behalf of the underprivileged and became the first female judge in New York City when she was appointed to the Children’s Court. In the 1950s she helped focus attention on the issue of de facto segregation in New York City schools. As part of broadcast journalist Edward R. Murrow’s recurring “This I Believe” radio news segment, Justine Wise Polier discussed the beliefs that motivated her.

Freedom means many things to many people. From my earliest childhood I saw it through the eyes of my parents as both opportunity and challenge to do battle for those in bondage, to achieve freedom of the spirit and mind for one’s self and one’s fellow men. Blessed by parents whose deepest joy was through service to their fellow men, who were deeply moral without ever being self-righteous, who were profoundly religious and therefore not sanctimonious, I learned that love of mankind became meaningful only as it reflected understanding of and love of human beings.

As an American Jew I have found that the great spiritual and moral traditional given to the world by the Hebrew Prophets have strengthened me in my quest for personal dignity and therefore in the struggle for the dignity of man and the freedom of mankind. The beauty and great traditions of my people as of my home have been sources of strength and inspiration in confronting the difficult problems faced by our generation in these troubled times.

Justine Wise Polier, "This I Believe," 1953. Script from radio broadcast, with introduction by Edward R. Murrow. From the Justine Wise Polier papers at the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America. Permission granted by the Schlesinger Library.

Negro-Jewish Relations in the North Excerpt on Growing Tensions

In recent months, a marked anti-Jewish prejudice has been revealed by Negro publicists.

On November 28, 1959, the Amsterdam News insinuated in an editorial that Jews (“one particular racial group”) dominated the radiology departments of New York City hospitals and blamed the Hospital Department for planning to deny promotion to a Negro roentgenologist and to fill a vacancy with a member of this same racial group. The editorial concluded by asking the Commission on Intergroup Relations to prevent “this type of racism.”…

Simultaneously one senses, although perhaps one cannot prove, an increase of anti-Negro attitudes in the Jewish community. The more important cause for this new fear and hostility is the movement of Negroes into what were formerly Jewish neighborhoods. The classic example is the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Central Park West and West End Avenue and, perhaps, the multi-storied apartment houses on the side streets, remain all-white enclaves but everywhere else the neighborhoods is changing into a slum. The inevitable deterioration of the public schools, the overcrowding in the streets, the increase in “mugging,” all bring about a panic withdrawal, either flight to the suburbs or the more expensive all-white East Side or a determined effort to insulate oneself by sending children to private schools and keeping them off the streets. This new fear and consequent hostility is sensed by Jewish leaders in a new opposition to public school integration on fair housing practice acts and a vast indifference to Federal civil rights legislation relating to suffrage. Judge Leibowitz was voicing this fear when he complained that women in his neighborhood were fearful of walking to their homes from the subway and articulating underlying attitudes when he appealed for a temporary ban on emigration.

Will Maslow, "Negro-Jewish Relations in the North," paper read at the annual meeting of the Association of Jewish Community Relations Workers, Arden House, January 11, 1960. Copy of paper, with note from February 19, 1960, from the Justine Wise Polier Papers at the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America.

Debate on Civil Rights involvement of Union of American Hebrew Congregations

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, now the Union for Reform Judaism, supported the work of the Civil Rights Movement. While many Reform Jews and their congregations applauded the work that the UAHC was doing, some synagogues felt that they were over-stepping their authority. In a series of letters that span a decade, board members of Hebrew Union Congregation in Greenville, Mississippi, outlined their position as Southern Jews. The Union of American Hebrew Congregations outlines its position in a response.

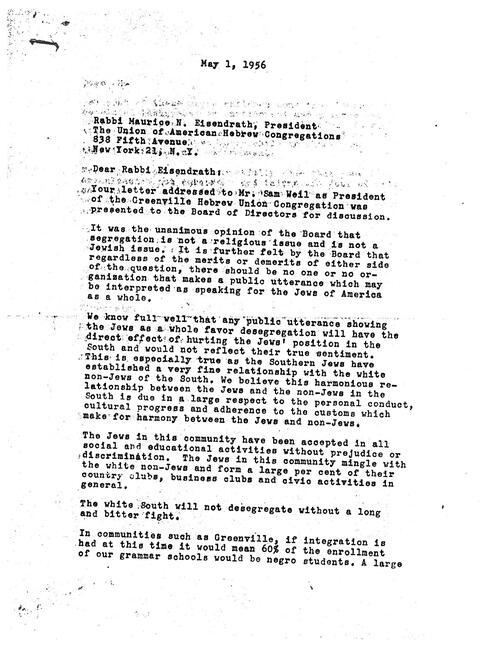

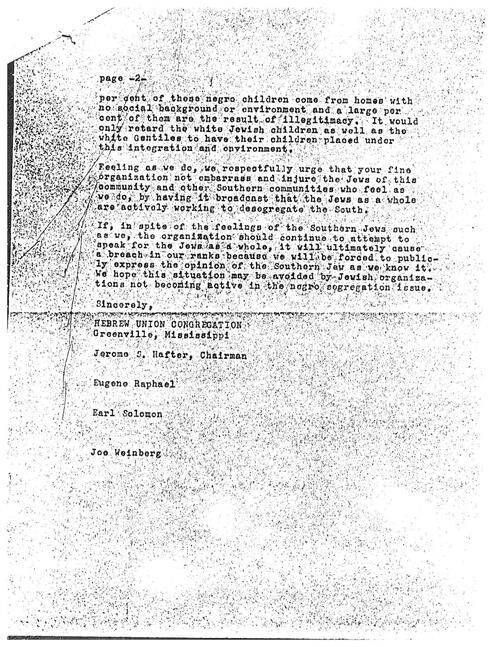

Letter from Hebrew Union Congregation to Rabbi Eisendrath, May 1, 1956

Letter from Hebrew Union Congregation from Rabbi Eisendrath, May 1, 1956, page 1 of 2

Hebrew Union Congregation to Rabbi Maurice N. Eisendrath, May 1, 1956, page 1.

Courtesy of the Hebrew Union Congregation Official Records, Greenville, Mississippi.

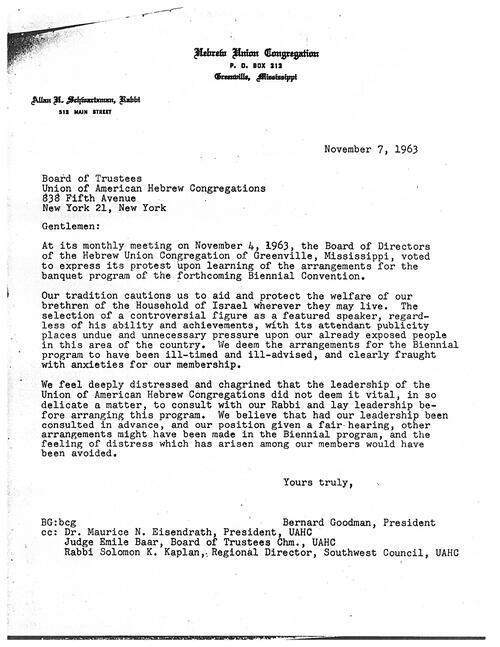

Letter from Hebrew Union Congregation to the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, November 7, 1963

Letter to the Board of Trustees of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations from Bernard Goodman (on behalf of the Hebrew Union Congregation) on the HUC's displeasure on the invitation of Martin Luther King, Jr. to speak at the UAHC Biennial, November 7, 1963.

Courtesy of the Hebrew Union Congregation Official Records, Greenville, Mississippi.

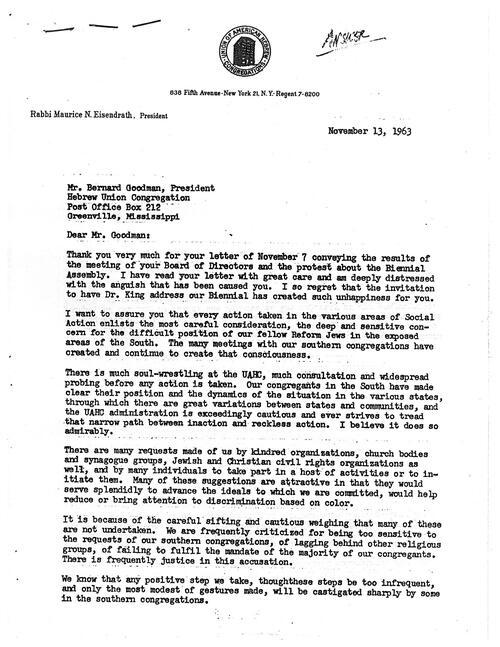

Letter from Rabbi Eisendrath to Bernard Goodman, November 13, 1963

Letter from Rabbi Eisendrath to Bernard Goodman, November 13, 1963, page 1 of 2

Rabbi Maurice N. Eisendrath to Bernard Goodman, 13 November 1963, Hebrew Union Congregation Official Records, Greenville, Mississippi. Permission for use granted by Richard Dattel.

Context for photograph of Neo-Nazi Demonstration

The marchers in this photograph (date and location unknown) are wearing armbands with swastikas on them, which suggests that they are Neo-Nazis. The signs they hold refer to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). On some signs the C in NAACP has been replaced by an overlapping hammer and a sickle, the symbol of the Communist Party in the Soviet Union, presumably to suggest that the NAACP was Communist—a charge that at the time was interpreted by some to mean that they were disloyal to the United States. The signs reading "NY Jew Heads NAACP" may refer to Kivie Kaplan, a Jewish man who served as President of the NAACP, 1966-1975.

Neo-Nazi Demonstration

Neo-Nazi demonstration against the NAACP.

Courtesy of the American Jewish Archives.

The Peddler's Grandson excerpt (pages 150-152)

In his autobiographical book, The Peddler’s Grandson: Growing Up Jewish in Mississippi, Edward Cohen describes what it was like to grow up with the dual identity of a southern Jew, who is viewed as an outsider both in the south and within the Jewish community.

During recess at Boyd and in gym at Murrah, the teachers organized a game in which everyone would encircle one person in the middle and try to hit him with a soccer ball. The child in the middle desperately tried to dodge the ball and could only end his torment if by luck he managed to catch it. The person who had thrown it would take his turn in the middle. The game was called, by students and teachers alike, “nigger baby.” No one ever remarked on the name. All I could think, as I threw the ball, was that I was glad it wasn’t “Jew baby.”

I’d worked at cultural anonymity since that first Rosh Hashanah when I was six, just as my predecessors had done when they moved the Sabbath to Sunday. I had been, at different stages of my life, proudly Jewish, then proudly southern, often simultaneously both, and it had always seemed possible to resolve or at least ignore the inherent contradictions. But during the civil rights struggle, my two selves, southern and Jewish, were torn apart.

I was profoundly ambivalent about the coming revolution, as were, I think, most of the Jews in Jackson. One part of me was deeply ashamed of and angry with Mississippi—with the Clarion-Ledger’s daily incendiary rhetoric about “mongrelization” and “race mixers,” with those surging riot police for that one moment I’d been in their path, with the idiocy of my classmates and their racial slurs, with the mulish intransigence of our leaders…Every new arrest, every new racial murder, made me want to disown my native state, which, along with Alabama, was nationally synonymous with prejudice and hatred.

Yet when I read the pious articles condemning Mississippi in the New York Times and the more strident screeds in the Village Voice, my southern side would get its back up, with contradictory and equal passion. Self-righteousness had always brought out the rebel in me, and the northerners who’s taken it upon themselves to cure our ills seemed fueled with a healthy dose of it. I knew things were desperately wrong in Mississippi, but, having a southerner’s pride, I didn’t like being told by outsiders how to fix it. They’ve got plenty wrong in their own backyards, I thought of the busloads of shining-eyed white students coming down like missionaries.

Cohen, Edward. The Peddler's Grandson: Growing Up Jewish in Mississippi (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1999), 150-152.

"The Maids and Black Jesus" excerpt

Eli Evans grew up in Durham, NC. In this excerpt from “The Maids and Black Jesus” in his book The Provincials: A Personal History of Jews in the South, Evans describes the relationship his family had with its black maids:

I was raised Southern-style—by the maid. No one can understand the mystery of the South without delving into this murmuring undertone—a relationship primordial, like parent and child, of discipline and need, shadowing every white Southerner throughout the rest of his life…

They are nearly as much a part of me as my parents are: the gentle arms, the stinging switch, bedtime stories, the Jewish dishes they cooked, and the gospel hymns they hummed while sweeping the porch in the white uniforms they picked out in Evans’ United Department store…

[Our maid Zola] had high hopes for [her son] Robert, to whom she preached about going to college, and she hugged my mother tearfully when Mother said, “Don’t you worry about paying for Robert’s college, Zola; he’s one more son we’ve got to send through school.”…

Once, when Passover came on a Saturday, my mother asked Zola if Robert could come over to help. “I thought we could teach him how to wait on tables,” Mother said.

“No thanks,” Zola answered without looking up.

“Why not?” Mother asked innocently “…pick up some extra money…it’s a mighty good thing to know.”

“Please, Miz Evans. I appreciates it and all, but I don’t want him to learn to wait.”…

Zola once invited me to come and watch Robert narrate a Bible story in a Sunday school play. She beamed at me at intermission, and whispered proudly, “No one else here had any white people come and watch them.”

Eli N. Evans, "The Maids and Black Jesus," in The Provincials: A Personal History of Jews in the South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005) 255-262

Stephen S. Wise statement to the Sub-committe of the Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare

Stephen S. Wise was a Reform rabbi who had dedicated his life to issues of social justice within and outside of the Jewish community. He was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and also served as the president of the American Jewish Congress. His daughter Justine Wise Polier also worked on behalf of underprivileged people. The quote below comes from Rabbi Wise’s testimony, as President of American Jewish Congress, during a Senate sub-committee hearing relating to discrimination in employment in

1947. [Exact date unknown.]

Our movement recognizes fully that equality of opportunity for Jews can be truly secured only in a genuinely democratic society. Accordingly, we seek to fight every manifestation of racism, to promote the civil and political equality of all groups and persons in America, and to support measures designed to safeguard civil liberties and to build a better America. We regard ethnic discrimination, whether directed against Jews, Negroes, Chinese, Mexicans, or any other group, as a single and indivisible problem and as one of the most urgent problems of democratic society.

Stephen S. Wise, President, American Jewish Congress, “United States of America, Before a Sub-committee of the Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, holding hearings on S. 984, a bill to prohibit discrimination in employment because of race, religion, color, national origin, or ancestry.” CLSA Reports, American Jewish Congress, New York. Source provided by Marc Dollinger and the American Jewish Archives.

Comments by Rabbi Milton Grafman about national Jewish leadership and the position of southern Jews

Milton Grafman was born in Washington, D.C., but spent most of his career as the rabbi of Temple Emanu-El in Birmingham, AL. Like many southern rabbis, Milton Grafman found himself caught between the realities of southern Jewish life and civil rights activists. He worked towards integration, but was opposed to disruptive protests that could lead to violence and undermine local, more moderate efforts. In the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, Grafman said the following in an interview with a rabbinic student at Hebrew Union College, who was working on a paper entitled “The Southern Rabbi and Civil Rights”:

“The Jewish leadership cannot travel faster than the rest of the population…we have to live with these people day-in and day-out. A freedom rider comes down, and a marcher, and a demonstrator… and I don’t know what he accomplishes, very frankly, except he goes back and he’s a hero—and he doesn’t have to live with these people. But we do, and our people have got to live with them…the only way we can be effective is to work with the Christians who are willing to be active in any given program—and certainly in the field of civil rights.”

Krause, Allen. The Southern Rabbi and Civil Rights, unpublished paper, 1967, Civil Rights, Box no. 1747,

American Jewish Archives, p. 82. Source provided by Marc Dollinger and the American Jewish Archives.

Excerpts from panel discussion reflecting back on the civil rights era in Jackson, MI

In 2001, the organization Facing History and Ourselves hosted a panel discussion with three individuals who had lived in Jackson, Mississippi during the time of the Civil Rights Movement. The following excerpts are taken from responses by the three panelists to a question about the experiences of Jews in their community who were not involved in the Civil Rights Movement.

Manny Crystal

“In my experience, in our business we never experienced that [pressure against Jewish businesses found elsewhere in the state]. We always worked black and whites together. We had blacks supervising people over whites. Now I use that in comparison to the time I went to Cleveland, OH, in the same period. And I toured a plant with 1,200 employees. And when we got back to the owner’s office…I said, ‘Johnny do you notice anything different about this plant?’ He said, ‘no.’ I said, ‘Johnny there’s not one black person in this plant, I said not even a janitor, a sweeper, nothing.’ So I asked the owner why. You know Cleveland is a very ethnic community also. He said ‘Manny, if I hired one black, everybody would walk out.’ We didn’t have that experience in the south. We had the ability of people working together; they didn’t socialize together. I think this is one of the big misinterpreted facts about the whole civil rights community. In the south we were always associated with blacks in the working community, in the living community. And up north that wasn’t true. So you didn’t have that inter-relationship that we have here. Whether that’s good or bad I don’t know…”

Bea Gotthelf:

“Well, I’m not disagreeing you… [but] my husband worked for a while with my father’s business, which was laundry and cleaning. And Harold got a phone call from a friend who was in the white citizen’s council, saying, ‘Do you have a man working there?’ I’ll say by the name of John Smith. And he said, ‘Yes I do.’ And he said ‘We want you to fire him. His child is one who is trying to integrate the schools, and we want him fired because of that.’ And my husband said, ‘I’m sorry, but he’s worked here for a number of years, he’s a good employee, and I won’t fire him for that.’ And this good friend said, ‘Well you’ll be sorry, you’ll lose customers, and there’s no telling what will happen to your business.’ So after that they had to hire a private detective to patrol the building, which they did for about a week, and then they decided nothing was going to happen. After our temple was bombed, they [African Americans] got together and marched from one spot to the Temple, to show their solidarity with the Jewish community, and I thought that was a very wonderful thing that happened.”

Elaine Crystal:

“I think that honestly those of us who were active were shunned by some of those in the Jewish community. They wanted to stay in the background and didn’t want to be up-front in any way. They felt that by hiding, they would not be noticed and would not be affected by it, but of course everybody is affected by it, as we know.”

Transcript from video of panel discussion at Facing History and Ourselves’ 2001 Civil Rights Tour, Jackson, MI,

Jewish Community Breakfast.

Mayor William Hartsfield with Rabbi Jacob Rothschild After the Bombing of The Temple, Atlanta, Georgia, October 15, 1958

Mayor William Hartsfield with Rabbi Jacob Rothschild after bombing of The Temple, Atlanta, Georgia, October 15, 1958.

Photo courtesy of The Temple (Hebrew Benevolent Congregation in Atlanta).

Rabbi Perry Nussbaum and wife after bombing of their home

Rabbi Perry Nussbaum and wife after bombing of their home. Courtesy of the Institute for Southern Jewish Life.