Jewish Radicalism and the Red Scare

Context

Emma Goldman was a Russian Jewish immigrant to the U.S. in the late 19th century. She was influenced by the Jewish secular Bundists in Russia, and she became politically radical—an anarchist—shortly upon her arrival in the U.S. Though Goldman was opposed to organized religion, she sometimes lectured in Yiddish and mentioned Jewish themes. The U.S. Government called her “the most dangerous woman in America” and she was ultimately deported in 1919 to the Soviet Union as an “alien radical.”

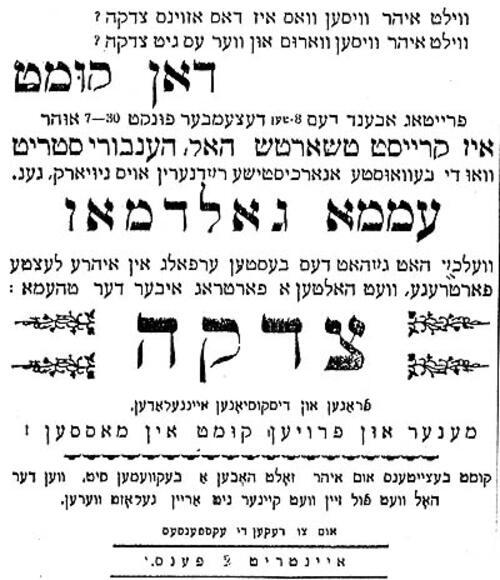

Emma Goldman Lecture on "Tzedakah," or Charity, December 1899

Courtesy of the Emma Goldman Papers.

Discussion Question

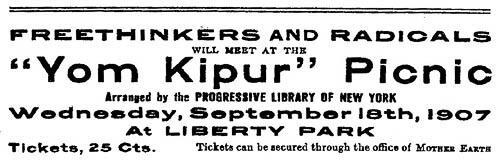

Advertisement for "'Yom Kipur Picnic" Organized by Emma Goldman and her Colleagues

Emma Goldman's non-traditional relationship to Jewish practice is evidenced by her participation in events such as this, scheduled on Jewish holy days.

Freethinkers and Radicals

Will Meet at the "Yom Kipur" Picnic

Arranged by the Progressive Library of New York

Wednesday, September 18th, 1907

At Liberty Park

Tickets, 25 cts. Tickets can be secured through the office of Mother Earth

Discussion Questions

- What do you think is the significance of having a picnic on Yom Kippur?

- What might a Jewish anarchist be saying about being Jewish by attending a Yom Kippur picnic?

- Why have the picnic on Yom Kippur specifically and not another day?

Context

Ayn Rand (originally Alisa Zinov'yevna Rosenbaum) was a Russian-American novelist, playwright, Hollywood screenwriter, and philosopher. Her philosophy, called Objectivism, rejected altruism in favor of self-interest and has been influential among Libertarians and some conservatives. Rand was called before HUAC to talk about the film Song of Russia. Producer Louis B. Mayer gave testimony saying the film was not meant as Soviet propaganda, and Rand, a witness “friendly” to the Committee, testified that it was absolutely propaganda.

Excerpt of Ayn Rand’s testimony before HUAC, October 20, 1947

McDowell: That is a great change from the Russians I have always known, and I have known a lot of them. Don't they do things at all like Americans? Don't they walk across town to visit their mother-in-law or somebody?

Rand: Look, it is very hard to explain. It is almost impossible to convey to a free people what it is like to live in a totalitarian dictatorship. I can tell you a lot of details. I can never completely convince you, because you are free. It is in a way good that you can't even conceive of what it is like. Certainly they have friends and mothers-in-law. They try to live a human life, but you understand it is totally inhuman. Try to imagine what it is like if you are in constant terror from morning till night and at night you are waiting for the doorbell to ring, where you are afraid of anything and everybody, living in a country where human life is nothing, less than nothing, and you know it. You don't know who or when is going to do what to you because you may have friends who spy on you, where there is no law and any rights of any kind.

McDowell: You came here in 1926, I believe you said. Did you escape from Russia?

Rand: No.

McDowell: Did you have a passport?

Rand: No. Strangely enough, they gave me a passport to come out here as a visitor.

McDowell: As a visitor?

Rand: It was at a time when they relaxed their orders a little bit. Quite a few people got out. I had some relatives here and I was permitted to come here for a year. I never went back.

Discussion Questions

- How does Rand talk about the Soviet Union?

- What evidence does she give in her testimony below that the film was propagandistic in favor of the Soviet Union?

- Why do you think Ayn Rand might give this testimony knowing it could potentially hurt the people who made the film?

Context

The following excerpt comes from an internal memo produced by the American Jewish Committee on July 31, 1950, in relation to the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg treason case.

Memo Regarding Propaganda Efforts from the American Jewish Committee

Considerable concern has been expressed over public disclosures of spy activities by Jews and people with Jewish-sounding names. The present situation is regarded as being potentially more dangerous than the situation which obtained during World War II; for now the enemy is seen as Communist Russia rather than as Nazi Germany.

The main reason for concern is the belief that the non-Jewish public may generalize from these activities and impute to the Jews as a group treasonable motives and activities…

Because it seems likely that the AJC will undertake some kind of propaganda campaign in connection with these problems, I should like to make some constructive suggestions along propaganda lines…

Instead of arguing exhortatively that Jews are not Communists, that they hate Communists, that they hate Russia, that Russia hates Jews, more positive approaches based on propaganda of fact can be used…

The following propaganda of fact ideas may be tried out:

- Stories about how Russia stifles and oppresses its various minorities, including Jews, despite its claims to the contrary.

[items 2 through 4 have been omitted...]

- Stories of how Communists are fought in this country through institutional means such as labor unions (Dubinsky [David, President of the ILGWU 1932-1966] kicks them out) and through government, featuring the work of such U.S. attorneys as Irving Saypol. (In this connection it should be pointed out that Saypol and other Jews on the “right side” may have as much or as little chance of recognition as do Jews on the “wrong side.”)

- Stories and reprints of stories on Russian attacks against Israel, against Zionists, against the use of the Hebrew language.

- Reprints and stories of Israel siding with the United Nations against Korean aggression.

- Stories of how the present government in Israel keeps down Communists…

Discussion Questions

- About what does the memo suggest American Jews should be concerned?

- What does the memo suggest the American Jewish Committee (AJC) do on behalf of the American Jewish community?

- Do you think the American Jewish Committee was acting in the best interests of the American Jewish community given the circumstances of 1950?

- What might the AJC have done differently?

Context

Gerda Lerner was a writer and community organizer (and later a pioneering women’s historian) and her husband was a film editor; they lived in Hollywood during the early part of the McCarthy era.

Gerda Lerner writes about the Communist Party and the Hollywood 10

Some time late that year [1946] I joined the Communist Party. It was not, at the time, a major step or a difficult decision. Later, red-baiting and witch-hunting would make of the act of “joining” or “leaving” the CP a momentous decision with not inconsiderable consequences. The fact is that I can neither remember exactly when I joined nor where and when I first attended a branch meeting. All it meant at the time was an added number of meetings each week and the obligation to read.

What was important to me then about joining the Communist Party was that I believed I was joining a strong international movement for progress and social justice. I had no particular love for the Soviet Union, although the heroism of its people during the war had impressed me as a sign that there was indeed a vibrant experiment in social reconstruction going on in that country. After Hiroshima and Churchill’s “iron curtain” speech it seemed inevitable that sooner or later the capitalist nations would unite against the Soviet Union, as they had in the period just after the Bolshevik revolution. As it had been essential to defend democracy in Spain, so it seemed essential to defend and maintain the existence of the socialist experiment in the Soviet Union.

At present, we have all but forgotten the radical origins of democratic society in the United States. After fifty years of the cold war and internal red-baiting witch hunts, one is expected to explain why reasonable persons of good will, social conscience and patriotism could ever have worked for radical alternatives to the capitalist system. All I can say is that fifty years ago it seemed a reasonable choice to make…

The story of the Hollywood Ten has been told many times since and they have become the symbol of the blacklist. While they certainly deserve their place in history and while their defense of First Amendment rights should be celebrated, they were not typical of those victimized by the blacklist. Most of them were highly successful writers, with long Hollywood careers and some wealth and savings. On the other hand, most of the people who would fall victim to the blacklist were “little people.” The blacklisted writers could attempt to sell scripts under pseudonyms; they could write for other media, but blacklisted actors, teachers and civil servants were thrown out of their professions for good….

Fear became our daily companion. A strange car pulling up near our house, a man emerging from it, made the heart race and the knees grow weak. The subpoena servers liked to come around at mealtimes, or quite early in the morning. Each morning, you peeked out from behind window screens to see if they were there. Friends told stories, all of them bad. The FBI followed the wives of those subpoenaed; two men in regular cars would be parked near the school entrance as the wife picked up the children. They would knock at your door: two men in business suits, flashing their badges. “We’d just like to talk to you for a few minutes, ma’am,” they would say in their clipped, rehearsed voices.

“I have nothing to talk to you about” was the only answer that worked, but it would make them follow you for days, questioning your neighbors, your employer, your friends. Neighbors would avoid you; others, friendly, would warn you what was up. “You’re wanted by the FBI.”

Those were stories. The chilling effect truly worked, like slow corrosive poison. We lived in fear, we ate it; we slept in fear, with nightmares of violence and useless resistance… We had committed no crime, violated no law. We worked and paid our taxes; we cut our lawn and put the garbage out on time. We were good neighbors and by all normal standards we were good citizens. We voted regularly and in all off-year elections.

You began to wonder about yourself. Maybe you were avoiding the FBI interview because of your cowardice, your secret knowledge that, pressed hard enough, you would answer with whatever they wanted to hear: the names of friends, their version of your political life, your redefinition of yourself as having been naïve, duped, or coerced or betrayed, just so you could save your own skin, your job, your children. You hunkered down, trying to stay calm and do the daily work that needed to be done, waiting for the next blow.

Discussion Questions

- How does Lerner describe the meaning of belonging to the Communist Party?

- How does she describe her experiences during the McCarthy era?

- What kinds of choices does Lerner suggest were open to people like herself regarding cooperating or not with HUAC?

- What other choices do you think people had?