Riding the Wheel of Health: The American Jewess's Progressive Perspective on Women's Bicycling

As part of our efforts to provide easy online access to primary sources in Jewish women's history, in 2006 the Jewish Women’s Archive (JWA) digitized The American Jewess, the first English-language periodical directed at American Jewish women. Rachel Salton used JWA’s digital version of this significant historical resource, hosted on the University of Michigan’s “Making of America” digital library website, for a paper written for Professor Jonathan Sarna’s class on American Judaism at Brandeis University in spring 2009.

Riding the Wheel of Health: The American Jewess's Progressive Perspective on Women's Bicycling

Rachel Salston

NEJS 162a: American Judaism

Professor Sarna

April 23, 2009

The American Jewess, edited by Rosa Sonneschein from the first issue in April 1895 until she transferred its control to a publishing group in the summer of 18981 offered guidance to the American Jewish woman of the era in such areas as fashion, the issue of synagogue membership for women, and household advice. The magazine also contained a regular column titled "Popular Science and Medicine", which addressed issues of diet, weight loss, general health habits, basic lessons in human physiology, and suggestions about proper exercise.

A curious suggestion often enforced as a beneficially healthful practice was the riding of bicycles for the sake of exercise. This encouragement, let alone the very discussion of women riding bicycles reflects the image of the American Jewess that the like-named magazine sought to portray. Columns authored by physicians and Sonneschein's editorial comments mention this suggestion several times. At that time, the bicycle was seen as a very controversial instrument for women. As will be revealed, another women's magazine of the era, The Ladies Home Journal makes no suggestion that women should ride2; In addition, the health columns in The American Jewess contain statements supporting dress reform, especially in such areas that will be beneficial to women's health; the articles persuade the casting off of the corset and high heels (especially during sport). The advisement of a controversial form of exercise and dress for the sake of health in part is due to the Jewish character of the magazine, indicating a non-condemning view of female sexuality, a valuing of progressiveness as an approach to becoming Americanized, and the valuing of health over vanity.

In the eighteen-nineties, the bicycle reached heights of popularity, especially amongst women of society, creating the so-called "New Woman on wheels".3 As progressive Frances Willard recounted in her 1895 memoir:

as a temperance reformer I always felt a strong attraction toward the bicycle, because it is the vehicle of so much harmless pleasure, and because the skill required in handling it obliges those who mount to keep clear heads and steady hands.4

Willard's contained her process by which and her thoughts concerning how she learned to ride a bicycle at the age of fifty-three. In addition to her role as a temperance reformer, Willard was a suffragist, ending her book with a message of encouragement for other women, "Moral: Go thou and do likewise!"5

And they had done so already. In 1894, Annie Londonderry, a young Jewish mother of three became the first woman to ride a bicycle around the world. Londonderry, whose real name was Annie Cohen Kopchovsky6, left the Massachusetts State House on June 25, 18947 and returned to Boston on September 24, 1895, having completed her journey in Chicago on September 12th8. Throughout her trip, Annie's style of dress changed in a manner reflecting he status as a "New Woman". As she rode a men's bicycle with a crossbar, the Victorian long dress she had wore at the beginning of her voyage became highly impractical. She opted for bloomers, the baggy women's trousers made famous by Amelia Bloomer, and then finally for a man's riding suit (Figure 1).9

Annie Cohen Kopchovsky, known as Annie Londonderry, in the final incarnation of her bicycle riding costume. She was the first woman to ride a bicycle around the world in 1894-1895. Source: Annie Londonderry--the first woman to bicycle around the world, by Peter Zheutlin. © Peter Zheutlin.

Although The American Jewess makes no formal reference to Annie and her circumnavigation, the health and exercise columns make great mention of dress and cycling habits, which Ms. Londonderry would have subscribed to. Perhaps they are the product of Annie's inspiration as a Jewess on wheels. "Popular Science and Medicine," the magazine's regular health column, was authored by Dr. Julius Wise10, a very famous writer for several Jewish publications of the era. He was described in his obituary as "bold, vigorous, sarcastic, honest, a hater of shams, and yet with it all a God-fearing, religious man … never aught but chivalrous in writing of women"11. Also a notable physician, having assisted during a yellow fever epidemic in 1870 and 1878 as a professor of medicine at Memphis Medical College12, it can be assumed that those who read Wise's column trusted the information as solid medical advice. This assumption is an important one, as Wise's medical opinion was controversial given the debates over women's health in this time.

In his first installment of "Popular Science and Medicine", Wise presents the following general health advice:

Air, light, water[,] and exercise are indispensable to good health, and consequently to good looks. But it is not necessary to take them as if they were medicines, as is done by many people. There are no individuals more unpleasant to themselves and others than those who are constantly doing something for the benefit of their health.13

Exercise, Wise argues should be a pleasurable activity taken not as drudgery, but as an activity that should become commonplace in one's lifestyle. One should consider it pleasurable pursuit that one would implement even if in a completely sound state of health, a so-called leisurely lifetime activity. This statement of exercise's purpose carried through into future manifestations of the health column.

Although Julius Wise's later columns in the later issues of the first volume of The American Jewess deal with primarily with disease control, personal idiosyncrasy, and childcare, his successor a columnist returned to the discussion of women's health and fitness originally set forward by Wise. Dr. Carleton Simon14, a young, European educated psychiatrist, made his debut in The American Jewess not in a formally titled column15, but in a blatant argument titled "Why Women Should Ride The Wheel." As Simon was a psychiatrist, one of the first points he addresses is the bicycle's "benign and healthy effect on our physical and mental welfare."16 In the same issue of The American Jewess, beginning on the next page, a nine-page highly detailed and illustrated spread explaining how bicycles are constructed is featured.17 It is noted several times throughout the article of what impressively sound and intricate structure the bicycles in the factory featured are. As writer Monroe Sonneschein18, comments,

Scientific men who have made bicycle-building their study all aggress that the construction of a modern safety [bicycle]19 is one of the most delicate and intricate problems in mechanics…. And right here let me state that too much rigidity in a frame is almost as faulty as not enough of it.20

Bicycles, according to Sonneschein's lengthy description, are precise and beautifully designed modern marvels. Like an expertly tailored dress might be described in The American Jewess's fashion column21, the bicycle's production makes the resulting "safety" appear to be elegant and desirable to the fashion connoisseur. In addition to the articles suggesting that the modern American Jewess should "ride the wheel", the magazine occasionally gave away promotional children's and women's bicycles as a reward for attracting ones friends to subscribe to The American Jewess. One such promotion appeared in February 1896 (Figure 2), months before Dr Carleton Simon's endorsement. Obviously, the "free" $100 bicycle advertised was paid for by the one hundred $1 new subscriptions to The American Jewess.

Given The American Jewess's frequent discussion of bicycles, one might assume that as a magazine with a smaller circulation22, the effect of a minority group as its target audience, its contents and comments on current events would in some way represent the discussions in more mainstream media. It is, however, a more discursive publication than its main secular counterpart of the time. The Ladies' Home Journal, under the editorship of Edward Bok23 was the first magazine to reach an audience of one million readers24. Like The American Jewess, it contains articles addressing fashion, beauty, hygiene, health, and fitness25. Its health related articles provide guidance for similar health concerns such as diet, weight loss and exercise. The Ladies' Home Journal does not, however, mention the prospect of a woman on a bicycle in its fitness columns during this period. Its health advisories often resemble the following,

Among open-air amusements there is no form of exercise more pleasant or healthful for women than that of rowing…. The skill shown in managing a boat gives an agreeable sense of power, and helps to create a feeling of independence.26

This evaluation of the benefits of rowing for exercise serves as a counterargument to those who advocated women's use of bicycles. As suffragist Susan B. Anthony explained, "Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world," a woman on a bicycle represents, "the picture of free and untrammeled womanhood."27 It is a symbol of freedom and modernity. Frances Willard comments in A Wheel Within a Wheel that riding had a "gladdening28 effect … on … [her] health and disposition."29 Considering that Willard's book had been released in the early years as the Bok's editorship of the Ladies' Home Journal, the most widely circulated woman's magazine30, one would expect to find some comment in the health notes discussing the benefits of cycling. But not one reference can be found. Even though the exercise suggestions range from "rowing, drilling31, … swimming", "rowing"32, and posture exercises performed while sitting, standing against walls, and walking33. The only reference to cycling is a single blurb, titled "Rules for Men Who Ride Wheels". It begins with the statement; "To the man seeking exercise there are features in bicycling that especially commend it for worthy consideration."34 Although it is possible that this one reference is a cryptic message to the magazine's mostly female readers that they might also receive benefit from cycling, the address of women's bicycling in The American Jewess provides profoundly more commentary on the issue.

In his article "Why Women Should Ride the Wheel", Carleton Simon recounts,

in the many instances that I have advised the use of the wheel, as a healthy and excellent means of exercise, various parents have thrown their hands up … and astoundingly asked me, "Why, Doctor! I have always heard that the use of the bicycle is injurious to a woman or girl." I have attempted also to trace these reports to their foundation, and have invariably found the cause of objection to be due to prejudice-the result of ignorance.35

The comments of the parents of Dr. Simon's patients are reflective of the severe skepticism about women riding bicycles in this decade. Bicycling was considered to be "injurious", as many persuasive skeptics argued that cycling "may suppress or render irregular and fearfully painful the menses, and perhaps sow the seeds for future ill health"36 or could "injure the kidneys, liver and urinary tract, some even suggesting that what might begin as a minor side-effect from the vibrations of the wheel could eventually lead to death."37 While none of these supposed health risks were actually dangers to female cyclists, they represent the resistance against the riding of the bicycle; they are excuses for less scientific concerns.

The position in which a woman sits upon a bicycle seat made many traditional Victorian skeptics uncomfortable. It was believed that straddling a bicycle seat combined with the motion of pedaling would lead to sexual arousal. In attempts to prevent this perceived problem, "hygienic" seats were created in different shapes and with different placement of padding than standard seats. Handlebar heights were adjusted to position the rider in what was seen as a less stimulating angle.38 Despite these revisions to the bicycle's structure, many still resisted allowing their daughters to ride bicycles and the Ladies' Home Journal makes no suggestion that a woman should ever ride one.

This unspoken opposition in the Ladies' Home Journal can be interpreted as an application of Victorian sexual mores. Editor Edward Bok's editions of the magazine revere domesticity, essentially opposing all progress except "that which would enable women to improve themselves within the parameters of the middle-class women's role … which, … Bok defined as 'domestic statesmanship'"39. Bok is further criticized as being "pedantic no matter whom he addressed … Bok lectured, scolded, and patronized women."40 The bicycle, the symbol of the "New Woman" encouraged women to wear pants, abandon corsets, and enabled women to be mobile and leave the home if they wished.41 The "wheel" was directly contrary to the Ladies' Home Journal's ideals.

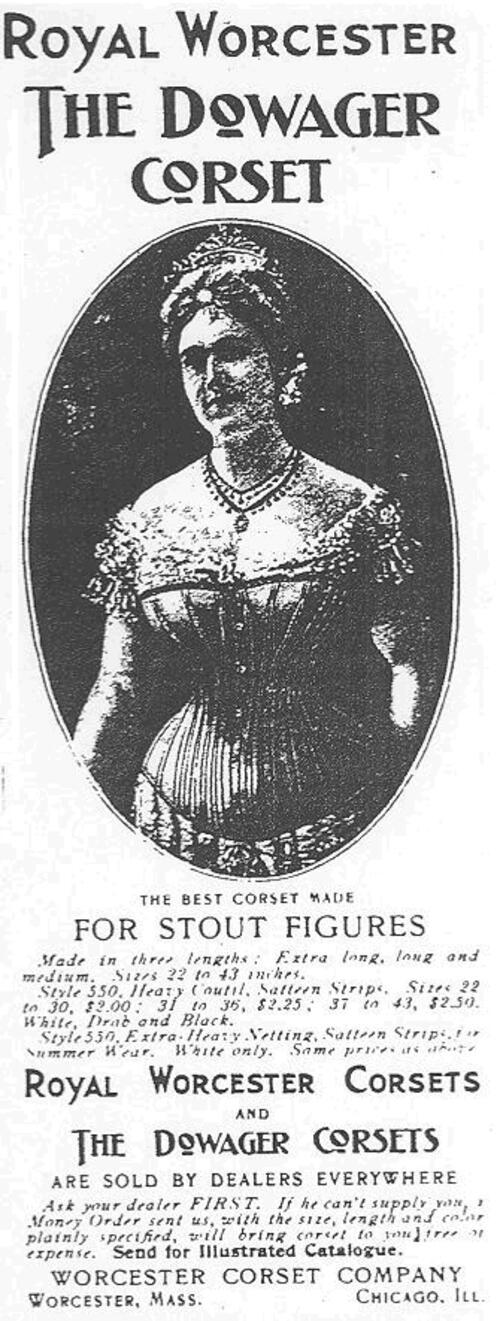

The American Jewess, on the other hand was a progressive magazine suggesting that women should embrace progress and become more modern. Unlike other magazines of the time, which advertized corsets on several pages every page of the magazine, including the Ladies' Home Journal, which featured an advertisement for a "Dowager Corset … For stout figures,"42 on the same page of the article in which it discussed appropriate exercise (Figure 3), suggesting that many of their readers did not make exercise a part of their lives, remaining "stout" and seeking to vainly disguise it rather than live healthy lives, The American Jewess seldom advertised corsets. Among the few corset advertisements ever printed in The American Jewess is for a bicycling corset (Figure 4), "The only Corset that gives support without impeding the perfect movement of the body. No brass eyelets."43 This is the first incarnation of the sports brassiere. The advertisement shows an athletic woman happily on a bicycle. The place the magazine argued that she belonged.

In the fourth issue of her magazine, Rosa Sonneschein defended the woman cyclist from various criticisms received,

The Bicycle, or rather the Bloomer girl is at present the most abused of her sex. A merciless and universal decree pronounces her the freak of the "fin de siècle."44 Poor little Bloomer girl, defenseless, defiant[,] and unadmired, thou glidest through streets, parks[,] and boulevards, the target of the evil eyes of chagrined conservative matrons. Pray let us be kind to the woman on the wheel…. There is no denying the fact: Bloomers are ugly and have a tendency to reveal what ought to be hidden. Lovely woman has no right to war upon beauty or propriety, and a girl in bloomers ought as little to be seen walking the streets as one attired in a ball dress … the outcry against the bloomer is due to the few indiscreet and foolish girls who dismount the wheel and take a walk. The place of the Bloomer girl is on her wheel.45

While Sonneschein and her magazine argue that Bloomer aught not be worn as proper street wear, the editor's statement takes for granted that women should be riding bicycles. The health columnist Carleton Simon did not "believe in the corset-a substitute being the corset–waist46, thereby giving the lungs room to perform their function, which is our very life."47 Dress, like bicycling should be reflective of increasing health and pleasure. It should not restrict that which makes us human.

This also relates to Simon's opinion that, providing the method of riding had been learned, there was nothing dangerous about a woman on a bicycle. The argument that a woman could become sexually aroused from her bicycle saddle and the corsets worn by some that restricted the image of a maternal body48, reflect a condemning view of female sexuality, a view present in the manner in which Edward Bok's magazine addressed women. The American Jewess, including Simon and Sonneschein's opinions, presents a Jewish image of the woman and her role. Female sexuality in Judaism is not an evil force that must be entirely suppressed. "There are no stories of parthenogenesis in Judaism and no theologically inspired guilt about sex."49 This opens doors towards progressive views of women's exercise; her health and happiness are extremely important to her role as a mother, she must not deny them for the sake of vanity.

Additionally, Jewish women have historically supported progressive causes in earlier times. The National Council of Jewish Women, an organization which Sonneschein supported and discussed in The American Jewess, was very active in the suffrage movement along with the Women's Christian Temperance Union, the organization to which cyclist Frances Willard belonged. It is no mystery that The American Jewess supported Jewish women's bicycling and their integration into American society, it was among many issues discussed that addressed the woman's role in American Jewish life.

The American Jewess's persuasive content advocating for its readers and all women to ride bicycles is a Jewish argument. It suggests that women should not sacrifice their health for vanity. They should not subscribe to the condemning views of women and female sexuality expressed by the outside world. That the entire publication unwaveringly suggests riding makes it a truly unique statement. Annie Londonderry would be proud.

Bibliography

Annie Londonderry. "Women on Wheels: The Bicycle and the Women's Movement of the 1890s."

Carleton Simon Papers. "Administrative History." M.E. Grenander Department of Special Collections and Archives.

Connolly, Christopher. "Women's lib arrived on bicycles." Mental Floss (May 20, 2008).

Damon-Moore, Helen. Magazines for the Millions: Gender and Commerce in the Ladies' Home Journal and the Saturday Evening Post, 1880–1910. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994.

"Dr. Julius Wise Dead." New York Times. April 20, 1902, page 7.

Goldman, Karla. "The American Jewess." Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2007.

Herlihy, David V. Bicycle. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

Humphry, Mrs. "How to Be Pretty Though Plain." Ladies' Home Journal, June 1899, 16.

Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. "Rosa Sonneschein." Jewish Women's Archive.

"Miss Londonderry's Trip Ended." New York Times. September 25, 1895, page 6.

Moran, Edward. "Bok, Edward," St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, 2000.

Schneider, Susan Weidman. Jewish and Female: Choices and Changes in our Lives Today. New York: Touchtone, 1985.

Simon, Carleton. "Health of Woman." The American Jewess, 2.12 (September 1896).

Simon, Carleton. "Why Women Should Ride the Wheel." The American Jewess, 2.9 (June 1896).

Sonneschein, Monroe. "How Bicycles are Built." The American Jewess, 2.9 (June 1896).

Sonneschein, Rosa. "Editor's Desk." The American Jewess, 1.4 (July 1895).

Spokeswoman Productions: It Starts With A Revolution. "Annie Londonderry: A Global Sensation." Spokeswoman Productions.

Summers, Leigh. Bound to Please: A History of the Victorian Corset. New York: Berg, 2001.

The American Jewess Project. "Introduction: The American Jewess." Jewish Women's Archive.

Warman, Edward B. and Mrs. Warman. "Five-Minute Talks on Good Health." Ladies' Home Journal, August 1899, 29.

Warman, Edward B. and Mrs. Warman. "Five-Minute Talks on Good Health." Ladies' Home Journal, September 1899, 28.

Willard, Frances E. A Wheel Within a Wheel. London: Hutchinson & CO., 1895.

Wise, Julius. "Popular Science and Medicine." The American Jewess. 1.1 (April 1895).

Zheutlin, Peter. "Annie Londonderry's Extraordinary Ride." Women In Judaism: A Multidisciplinary Journal, Volume 5.3 (Spring 2008).

Zuckerman, Mary Ellen, A History of Popular Women's Magazines in the United States, 1792–1995. Westport, Conneticut: Greenwood Press, 1998.

Footnotes:

1. This group of publishers remains unidentified and was unable to solve the magazine's financial troubles. In addition, it is evident that the magazine's content suffered greatly having lost Sonneschein as its editor. See Karla Goldman. "The American Jewess," Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2007. [return]

2. In the issues published during the same period as The American Jewess.. [return]

3. David V. Herlihy, Bicycle, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004): 245. [return]

4. Frances E. Willard, A Wheel Within a Wheel (London: Hutchinson & CO., 1895): 13. [return]

5. Ibid. 75. [return]

6. Kopchovsky's pseudonym is derived from the Londonderry Lithia Spring Water Company, which paid Annie $100 to affix their placard on her bicycle and to adopt their name. See Spokeswoman Productions: It Starts With A Revolution, "Annie Londonderry: A Global Sensation," Spokeswoman Productions. [return]

7. Peter Zheutlin, "Annie Londonderry's Extraordinary Ride," Women In Judaism: A Multidisciplinary Journal, Volume 5.3 (Spring 2008). [return]

8. "Miss Londonderry's Trip Ended ," New York Times, September 25, 1895, page 6. [return]

9. Peter Zheutlin, "Annie Londonderry's Extraordinary Ride," Women In Judaism: A Multidisciplinary Journal, Volume 5.3 (Spring 2008). [return]

10. Julius Wise was the son of the famous Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise. See "Dr. Julius Wise Dead," New York Times, April 20, 1902, page 7. [return]

11. Ibid. [return]

12. Ibid. [return]

13. Julius Wise, "Popular Science and Medicine," The American Jewess, 1.1 (April 1895). [return]

14. Carleton Simon (1871-1951) was born in New York City and was educated in medicine in Vienna and Paris. His work for The American Jewess was a very early part of his almost sixty year career as a psychiatrist and then a writer of criminology. Most notably, he served as Special Deputy Police Commissioner in charge of the Narcotics Bureau. His involvement in the progressive cause against narcotics (during his tenure, 100,000 people were convicted of narcotic related crimes in the United States and 27 foreign countries) can be linked to his advocacy for women's progressive causes such as bicycle riding and dress reform. See Carleton Simon Papers, "Administrative History," M.E. Grenander Department of Special Collections and Archives. [return]

15. Wise's column "Popular Science and Medicine" often did not use this title, however, Simon never used it. It would not return until Volume 7, Issue 5 (September 1898) when Dr. A.L. Wolbarst became the magazine's medical writer, publishing a series on anatomy and physiology titled "The Human Body as a Working Machine". [return]

16. Carleton Simon, "Why Women Should Ride the Wheel," The American Jewess, 2.9 (June 1896). [return]

17. Monroe Sonnechein, "How Bicycles are Built," The American Jewess, 2.9 (June 1896). [return]

18. Monroe Sonneschein was the youngest son of editor Rosa Sonneschein. This article is one of his many contributions of poetry, stories, and articles to the magazine. See Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia, "Rosa Sonneschein," Jewish Women's Archive. [return]

19. As opposed to earlier models, such as the Ordinary, the very difficult and dangerous to mount and ride high-wheel (sometimes as much as five feet in diameter) bicycles designed before the eighteen seventies. See Annie Londonderry, "Women on Wheels: The Bicycle and the Women's Movement of the 1890s." [return]

20. Monroe Sonnechein, "How Bicycles are Built," The American Jewess, 2.9 (June 1896). [return]

21. "Madame La Mode", which appeared in nine issues, comparable to the health and fitness columns' publications. A column on "London and Paris Fashions" appeared in fourteen issues. [return]

22. At the height of the magazine's success, it reached 31,000 readers. See The American Jewess Project, "Introduction: The American Jewess," Jewish Women's Archive. [return]

23. Edward Bok was the editor of the Ladies' Home Journal from 1889–1919. See Edward Moran. "Bok, Edward," St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, 2000. [return]

24. Ibid. [return]

25. These statements refer to the editions of the Ladies Home Journal published in the same time period as The American Jewess (1895–1899). [return]

26. Mrs. Humphry, "How to Be Pretty Though Plain," Ladies' Home Journal, June 1899, 16. [return]

27. Christopher Connolly, "Women's lib arrived on bicycles," Mental Floss, (May 20, 2008). [return]

28. She named her bicycle Gladys for this reason. [return]

29. Frances E. Willard, A Wheel Within a Wheel (London: Hutchinson & CO., 1895): 53. [return]

30. Mary Ellen Zuckerman, A History of Popular Women's Magazines in the United States, 1792–1995 (Westport, Conneticut: Greenwood Press, 1998): 10. [return]

31. Drilling perhaps refers to repetitive military style exercises. [return]

32. Mrs. Humphry, "How to Be Pretty Though Plain," Ladies' Home Journal, June 1899, 16. [return]

33. Edward B. Warman and Mrs. Warman, "Five-Minute Talks on Good Health," Ladies' Home Journal, September 1899, 28. [return]

34. Edward B. Warman and Mrs. Warman, "Five-Minute Talks on Good Health," Ladies' Home Journal, August 1899, 29. [return]

35. Carleton Simon, "Why Women Should Ride the Wheel," The American Jewess, 2.9 (June 1896). [return]

36. "Taking Chances," Iowa State Register, 28 August 1895. qtd. in Annie Londonderry, "Women on Wheels: The Bicycle and the Women's Movement of the 1890s." [return]

37. Ibid. [return]

38. Ibid. [return]

39. Helen Damon-Moore, Magazines for the Millions: Gender and Commerce in the Ladies' Home Journal and the Saturday Evening Post, 1880–1910 (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994): 83. [return]

40. Ibid, 71. [return]

41. Some suggested that this increased mobility would encourage women to leave their husbands. [return]

42. Mrs. Humphry, "How to Be Pretty Though Plain," Ladies' Home Journal, June 1899, 16. [return]

43. "Advertisements," The American Jewess, 2.6 (March 1896). [return]

44. End of century. [return]

45. Rosa Sonneschein, "Editor's Desk," The American Jewess, 1.4 (July 1895). [return]

46. Similar to the bicycle corset advertised. [return]

47. Carleton Simon, "Health of Woman," The American Jewess, 2.12 (September 1896). [return]

48. Some women wore corsets during pregnancy "to ensure that an image of womanly innocence was maintained despite evidence of sexual experience." See Leigh Summers, Bound to Please: A History of the Victorian Corset (New York: Berg, 2001): 39. [return]

49. Susan Weidman Schneider, Jewish and Female: Choices and Changes in our Lives Today (New York: Touchtone, 1985): 219. [return]