Blu Greenberg

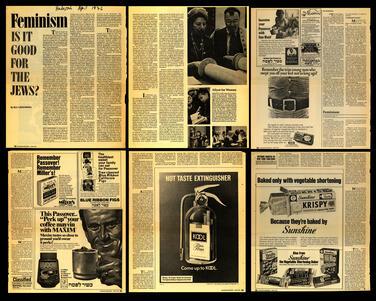

This artifact summons to memory an event that was a turning point in the life of American Jewish women – the first National Jewish Women’s Conference, held at the McAlpin Hotel, February, 1973. Skillfully organized by a handful of young women, the conference placed the broad feminist agenda at the heart of contemporary Judaism and community consciousness. It attracted 500 women (and one man) from across the entire spectrum of Jewish life.

The artifact also represents a turning point in my life: It represents my first foray into the dialectics of religious feminism, my first major public address, and my first published article on a subject that would engage me for the next 32 years.

From the conference, I learned many things:

• Probing an issue directly through the original sources and not relying on pre-digested information was essential. Preparation for this talk – my first systematic look at the issue – turned up some interesting correctives. The accepted notion in Orthodoxy was that women were on a pedestal, hierarchy did not exist, and gender differentiated roles/status were from Sinai, thus unalterable. True, Jewish women were protected and respected, valued and honored in the tradition. But there were also areas of closed access, unequal dignity, and outright disabilities for women. Furthermore, over time, change had come – especially religious education for women and attempts to ameliorate the plight of the agunah (literally, “chained wife” – a woman whose husband won’t grant her a religious divorce). All this had to be addressed.

• Feminism was an entry point for many women into Judaism and not an exit as other modern social movements had been.

• There was enormous value and power in cohorts.

• The difference between knowing a thing by observing others perform and knowing through first-hand experience had significant implications for women’s ritual.

• One could critique the tradition from within yet remain a faithful daughter; one could make tradeoffs and compromises to remain within community yet not lose one’s feminist aspirations or credentials.

• Feminists could be as Orthodox in their beliefs as traditionalists were in theirs. My critique was two-pronged: what Orthodoxy and feminism could learn from each other. Some in the audience welcomed the critique of Orthodoxy, but bristled at the critique of feminism. Happily, there has been great change in each sector during these past 30 years. Feminism yielded its radical edge, turned unqualifiedly family friendly, and became more inclusive of men. Orthodoxy has integrated values of gender equality to an extent unimaginable three decades ago.

The conference changed my life. How fortunate I was to be part of an incredible historical moment!

Author and lecturer Blu Greenberg has published widely on contemporary issues of feminism, Orthodoxy, and the Jewish family, as well as on other subjects of scholarly interest. Amidst a myriad of public roles, she chaired the first and second International Conferences on Feminism and Orthodoxy in 1997 and 1998 and is founding president of JOFA, the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance. She is author of On Women and Judaism: A View from Tradition; How to Run a Traditional Jewish Household; Black Bread, Poems after the Holocaust; and King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, co-authored with Rev. Linda Tarry. Greenberg is a member of the Jewish Women’s Archive Honorary Committee for the Celebration of 350 Years of Jewish Women in America.