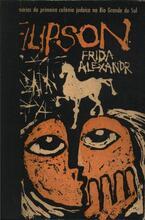

Widows in the North African Jewish Communities of Late Ottoman Palestine

Jews of the Moroccan city of Fez, ca. 1900. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The experiences of the many widows among Jewish North African immigrants to Palestine during the 1800s were unique and difficult, as they lacked both husbands and, in many cases, a stable home and income after migrating to a new place. But they also enjoyed a degree of independence, which inspired different motivations for making aliyah, beyond familial duty or obligation, and offered them the chance to realize their aspirations. Since women traditionally could not participate in prayer and Torah study, migrating to Palestine was a demonstration of faith. Once arrived, they were impoverished and faced a housing crisis, but, drawing on community networks, many Maghrebi widows were able to settle in Erez Israel and contribute to their communities.

Introduction

During the nineteenth century approximately two-thirds of all adult Jews in the Holy Land were women. This significant majority—nearly two women for every one male—was due to the overwhelming number of widows in the country.

The lives of widows who at some stage immigrated—as children with their families, as married women, or as widows—from North Africa to the Jewish communities of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Palestine, underwent changes, due to both immigration and widowhood. Such changes demonstrate the reformation and redefinition of their status and its boundaries, both in their communities and, more significantly, in their own eyes.

Widows in traditional societies, Jewish as well as gentile, posed a threat to the stability of the community: they were no longer under the patronage and authority of their fathers, brothers, or husbands, and for the first time in their lives they were independent. As widows, these women became legal entities in their own right, able to make their own decisions and manage their own affairs. In traditional Jewish society in Europe and in the Middle East, as well as in early modern Christian society, widowhood was effectively a “passport to freedom” (Lamdan 2000, 196). However, in fact this independence was often independence only as perceived by the widows, as economic necessity and social limitations often curtailed their actual activities. With the change in personal status from married to widowed, almost overnight these women were pushed to the sidelines of their communities and even ostracized from them. Although as widows they rose to the status of matriarch of their respective families, they were likely to become a burden upon their families or communities. Alternately they threatened society with the possibility of developing independent lives, posing a problem for traditional society: the empowerment of the traditional woman who did not “belong” to a man in a patriarchal society (Freist 1999, 165).

Immigration presented women with alternative forms of independence, as well as a myriad of problems. While women were subject to discrimination and constraints because of their sex, the course of migrating and resettling allowed and even required them to find employment and housing and to form new relationships with employers, neighbors, and communal and government representatives. At the same time these women protected and preserved many of the customs and forms of family relations that seemed, to them, to serve their interests and fought those that threatened their position. These processes allowed women to imagine, define, and identify themselves as somehow apart from the larger communities into which others had confined them. Such new definitions not only presented a possibility of empowerment for the immigrant within her new society, but also redefined her status within her family. These processes simultaneously transcend the individual and reflect broader changes in the content and meaning of social categories. Immigrant women are thus “active negotiators of the cultural values that they choose to accept” and continuously transform their cultural frameworks (Friedman-Kasaba 1996, 38–39).

The combination of these two major ruptures—in geographical location due to international migrations, and in family status due to the death of a spouse—present unique circumstances for studying women in traditional society and their reformulations of social relationships and societal constraints on space and place. The changing landscape of late Ottoman Palestine, with its ever-increasing and diversifying Jewish population due to migration, high mortality rates, and its perceived spiritual qualities as the Holy Land, created propitious opportunities for redefining, re-imagining, and relocating physical and social identities, particularly for women and most significantly for widows, often without extended family in the city.

A wealth of demographic information can be culled from contemporary censuses carried out in the Jewish communities of nineteenth-century The Land of IsraelErez Israel. In most instances the Jewish population was enumerated by household, with detailed information relating only to the male head of the household. However, the numerous widows in each of the communities were enumerated on separate, detailed lists. These lists provide a relatively reliable framework for studying widows. Although the demographic information from these lists cannot reconstruct a comprehensive picture relating to all women, it does provide a relatively reliable framework for studying widows.

Additional descriptions of North African Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.aliyah in travelers’ journals and diplomatic papers, as well as oral documentation collected from elderly female informants, descendants of those women immigrant (female/sing.; individual(s) who immigrates to Israel, i.e., "makes aliyah."olot), open a window into the lives of their grandmothers.

Demographic Instability

The number of North African Jews residing in Palestine grew from a few hundred at the beginning of the nineteenth century to nearly eight thousand at the outbreak of World War I. By the mid–1870s North African Jews comprised approximately one-quarter of the Jewish population of Palestine, Jerusalem excepted. However, the adult population was not evenly divided between males and females: the overwhelming majority was female. One reason for this is to be found in patterns of aliyah, differing for families and singles, the latter primarily widows. A combination of differential mortality rates and marriage patterns, both in the Maghreb and in Palestine, created a demographic imbalance, which in turn created more potential for women to remain widows, even at a relatively young age. This also resulted in a greater statistical possibility for widowed or divorced men to remarry than for women in the community. (Although polygamy did exist, its occurrence was relatively uncommon in the nineteenth century both in North Africa and in Palestine.)

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries there was a steep increase in the diversity and number of Jews arriving in the Holy Land, which not only balanced the negative growth rate of the local Jewish population, but also surpassed it, resulting in a significant overall increase in the Jewish population in the country.

Women’s Aliyah

While economic aspects have generally been emphasized in studies of women’s migration, particularly from less developed to more developed areas, one must consider not only economic factors of the labor market or marriage possibilities as motivating and influencing the decision of women to migrate, but also ideological and spiritual factors, as in the case of aliyah. Women, and particularly widows, seem to have desired aliyah as an expression of their spirituality and love of Zion. Traditional Jewish societies not only sanctioned aliyah for widowed women, but may also even have encouraged it. Widowed men, on the other hand, generally remarried and migrated as part of a family unit.

North African Jewish Women’s Love of Zion

A deep emotional attachment to the Holy Land and the belief in the inherent spiritual qualities endowed upon Jews who choose to live there explain the spiritual factors motivating Jews to migrate, and not only women (Ben Ya’akov, 2002). However certain aspects of the traditional love for Zion seem to have been defined specifically by gender. While men could and did express their attachment to the Holy Land, as well as elevate their status and well-being, through study, prayer, and communal activities, all while living in their own home communities, women seeking to express their love of Zion and spiritual uplifting had no direct part in such activities.

In spite of that, women, as well as men, believed in the special virtues endowed upon those living in the land—atonement of sins, answers to private individual prayers, health and longevity. The act of aliyah itself endowed each immigrant with special status: each Jew living in the country became a special envoy of his or her family, community, and the entire Jewish people. The women immigrated (literally, “ascended”) to the Holy Land in order to attain a higher level of holiness and to strengthen their faith, not to be part of a social revolution.

Non-formal expressions of religiosity have revealed women’s spirituality, otherwise unrecognized or marginalized (Weissler 1987, 1998). During the nineteenth century, for example, the phenomenon of saint veneration grew among North African Jews in general, and among Moroccan Jews in particular. Women as well as men, and perhaps more than men, participated in public celebrations (hillulot) and believed in the special powers of saintly men and women. This belief also encompasses an inherent connection to the Holy Land, accompanied by each individual’s personal participation in the process of redemption. The traditional love for and attachment to Zion of North African women was then generally expressed in forms outside the established rituals of the community, in hillulot, in private vows, and in the more radical deep desire for aliyah. For nineteenth-century women, aliyah and a changed lifestyle in the Holy Land presented possibilities for religious self-expression.

Many women vowed to move to the Holy Land to thank God for fulfilling a prayer and to visit the graves of famous rabbis such as Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai (second century) in Meron near Safed, or the cave of the Prophet Elijah on Mount Carmel. Upon their arrival in the Holy Land women prayed fervently and frequently at the graves of saintly rabbis, making supplications for their own personal benefit as well as for all Jews. The vows of women seem to have been much more private and informal than those of men and thus were not documented in communal records. However, they are remembered and relayed in stories transmitted by family members through generations.

Demographic Features of the Immigrants

One of the dominant characteristics of aliyah from North Africa to Palestine in the nineteenth century, like that of other Jewish migrations, is its pattern of family migration. Many women traveled to the Holy Land as widows, together with their extended families—with their married children, brothers, or uncles. In 1844, for example, eight families, including many widowed mothers and grandmothers, set out from the Moroccan city of Meknès on their way to Erez Israel.

Approximately twice as many women as men arrived in the country over the age of 60. Although nearly all the males were married at the time of their arrival, this was not necessarily the case for women. In spite of the fact that statistical information is available only for those women enumerated as widows at the time of the censuses, the difference is still significant.

Other widows arrived singly or in small groups. Due to the high mortality rates in Palestine and the limitations of the documentation, it is difficult to ascertain who among the widows listed in the various sources arrived as widows, and who among them were widowed long after arriving as girls or young married women. One notation on the 1855 census of Maghrebi widows in Jerusalem notes that “all the widows came with their husbands … however, much to our distress, they … died” (Montefiore Archives, ms 531). Various other examples note the aliyah of women traveling without family: In 1854 “ten elderly widows, and another of great skill in sewing, and also of great learning in the Bible and Codification of basic Jewish Oral Law; edited and arranged by R. Judah ha-Nasi c. 200 C.E.Mishnah …” set out from Meknès for Palestine, traveling together with a group of several families (Messas 1968, 14). An 1855 list of widows in the Sephardic community in Safed enumerates some sixteen widows, all in their fifties or sixties, all of whom migrated in the same year from the Tunisian community of Jerba. The same census enumerates only five married men arriving from Jerba at this time, leading to the conclusion that most if not all of the women arrived as widows.

After a difficult life in Exile more women than men chose to spend their final years in the Holy Land. Nineteenth-century census lists reveal that twice as many women as men immigrated over the age of 60, many of them widows. Although they did in fact die there, the Jews from North Africa do not seem to have been motivated by the wish to die in the Holy Land and be buried there. Approximately a quarter of all North African immigrants arrived as children, under the age of fifteen; well over half of the men enumerated were in the prime of their lives, between twenty and 50; and less than a fifth were over the age of 50. Various memoirs record the activities of these olim who migrated in order to live in the Holy Land, quoting the Psalms, to “take pleasure in her stones and favor her dust” (Psalms 102:15),

After fulfilling their obligations to family and community, many widows were for the first time “free.” Thus they could finally fulfill their desires, vows, and dreams and migrate to Palestine. Such may be the case with the sixteen widows from Jerba and the eleven widows from Meknès. However, it must be added that limited economic resources, or funds made available to them by their families, often restricted their independence.

Social conventions generally limited the geographic mobility of women in traditional societies, although economic need, family obligations, and philanthropic activities often mitigated prohibitions. In addition, the position of women within their families and within their communities defined their boundaries, including their ability to migrate long-distance. Certain categories of women are in fact “selected out” for migration. Among those are women already at the fringes of society—single women and especially widows. Although older women once widowed not only retained their family status but in fact often achieved enhanced stature as the matriarch, this status should be distinguished from their practical everyday functions, which often became more and more peripheral to family activity in daily life. Jewish families may have recognized this distinction and thus accepted—and perhaps encouraged—the decision of their mothers and sisters to migrate. Aliyah was not only socially acceptable, but seen as a holy act in the eyes of the community.

Life in the Holy Land

After the decision to migrate, the painful separation from family and community, and the hardships of travel, widows faced new problems in the Holy Land. Jewish widows immigrating and settling in the Holy Cities of Safed, Tiberias, Jerusalem, or Hebron had the opportunity, the challenge, and indeed the necessity of redefining themselves in space and place: vis-à-vis their families and their communities of origin, vis-à-vis social networks, housing and economic exigencies in the cities in which they settled, and even in their own self-image and perceived status as residents of the Holy Land, as well as widows, often alone in the city.

A Crisis of Housing and Poverty

Housing was a primary issue for new immigrants and old-timers alike. As the Jewish population in all the cities of Palestine increased, additional living space was continually required. Existing housing in small rooms surrounding inner courtyards became overcrowded and conditions continually deteriorated. Although rooms were added in the open areas of the courtyards and on roofs, the demand for housing outstripped the supply. Most of the Jews rented their meager apartments from Muslims, and the market laws of supply and demand caused the annual rents to soar.

A small number of widows lived together with their married sons or daughters. This pattern of residence was the norm for widows in their communities of origin in Muslim countries and it seems to have been the only option available to them there, although young, childless widows often returned to the homes of their parents.

While the great majority of women, and indeed of the Jewish population in Palestine in general, were desperately poor, the plight of widows and orphans was particularly distressing. They barely survived in rented accommodations even with assistance from communal funds. An urgent need for housing for this specific group in the population constituted a challenge for the leadership of each of the communities. In Jerusalem alone there were over one thousand Jewish widows in 1875, including some two hundred in the Maghrebi community.

An ambivalent attitude towards widows—a discrepancy between often-sung expressions of esteem for a “Woman of Valor” (Proverbs 31:10) and the inferior status of women in daily practice—is apparent in the housing arrangements available to the majority of widows in Palestine. Many crowded together in small rented rooms and courtyards primarily or exclusively inhabited by widows.

In response to the desperate and growing need, private as well as communal projects were initiated to ease the housing crisis. Shelters (batei mehaseh) specifically for widows were established. Some were in rented rooms, funded by local or Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.Diaspora Jews; others were in rooms or buildings endowed to the various communities in religious trust (hekdesh or wakf).

Maghrebi Jews in Jerusalem created a seemingly unique solution to the widows’ housing crisis: within each of the community’s synagogue courtyards or annexed to the synagogue were rooms specified for poor widows. The Zuf Dvash synagogue complex, for example, founded in 1860, included at least one room for poor widows, who in turn cared for the maintenance of the synagogue (cleaning, lighting oil lamps) and the physical needs of those using it (such as preparing tea for those studying). Although one interpretation may see this as patronizing and denigrating, a reading more in line with the social strategies of traditional women suggests this arrangement may reflect the protected status of women, as opposed to subjected or dominated status, and that women themselves fought to retain such aspects as benefited them. Such living arrangements and daily tasks also gave these women greater accessibility to the holy, via direct contact with the synagogue and indirectly through those studying and praying. This solution seems to be unique to Jerusalem.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century Jews in the more crowded quarters of Jerusalem, Tiberias, and Jaffa were actively looking for solutions to the housing crisis. The most obvious alternative was housing on the fringes of the Jewish Quarter and adjacent to it, primarily in the lower-density, cheaper Muslim quarters. Often it was the poorer Jews who inhabited these areas of changing ethnic composition. In Jerusalem, for example, poor widows were given housing in ground-floor rooms of the North African community’s three-story building in one of the expanding but peripheral areas of the Jewish Quarter (in today’s Muslim quarter). The better upper floors of the building housed two synagogue-study rooms and several apartments for the rabbis and scholars.

However, even these endowed rooms could not keep up with the increasing needs of the community. New buildings were required, specifically as shelters for the poor, and primarily for widows. The more innovative began to look in the surrounding area outside the city walls, in the new neighborhoods which began to be established outside the city walls, first in Jerusalem in the 1860s and 1870s, then in Jaffa in the 1880s and 1890s, in Haifa in the 1890s, and in Tiberias at the turn of the century.

Communal housing for the poor was constructed on land available in the new Jewish neighborhoods, in close proximity to the housing of the more innovative or those with some means. In Jerusalem, the Moroccan Mahane Yisrael neighborhood was established in 1868. As was the custom in Jerusalem, a synagogue was established there, with the ground floor rooms set aside for poor widows and orphans. The male communal leaders, publicly acknowledging their traditional responsibility and obligations to the poor, the widows and the orphans, as well as their inability to deal with the problem at hand, described the desperate situation in an appeal for donations:

… we have one community-owned courtyard designated for the poor [in the Mahane Yisrael neighborhood], but it is insufficient for even a third or a quarter of the needy, and in each room six and seven widows live together in great poverty, and others are abandoned on the streets, as the community has no money to rent housing for them.

Economic circumstances more than anything else seem to have dictated the location of housing for the poor. Communal and personal funds were severely limited. On the one hand, “public housing” was located in the cheapest areas and those usually farthest from communal centers. On the other hand, housing for poor widows was also located in central areas, in buildings dedicated to the communities, usually after the owner’s death. In the North African community of Jerusalem women, housing was even located in the very center of communal activity, adjacent to its synagogues, both within the city walls and outside them. Again it seems that a basic cause for this was economic—here, in the synagogue courtyard or building, space was already controlled by the community. However, one must also acknowledge the priority given to widows in this community’s allocation of space.

Occupations and Employment

The large numbers of women and especially widows in the Jewish communities of Palestine created new realities and new exigencies. As most of them were poor and without family support, many relied on weekly communal aid for their most basic needs. Prior to making aliyah, most of these same women had contributed to the emissaries who collected funds for the Jewish communities in the Holy Cities. Although they did not intend to use these monies themselves, when they fell on hard times after their settlement in the country they did expect to receive support. However, with the growing numbers of needy and increased expenses and communal responsibilities, the coffers were continually empty.

The meager allotments that the widows received, even smaller than those offered the men of the community, could not cover the minimal expenses of basic housing, food, and clothing. Although in the Maghreb women did work for pay, such work was done in their own homes or in the homes of others and as such, little was recorded. In the cities of Palestine, their work was more prevalent and more visible, as well as of greater necessity. A contemporary report noted, “The distress amongst the Moroccan Jews was much worse than amongst any other of the Jewish population” (Luncz [1882] 1982, 189). Social conventions could no longer limit women’s activity since basic survival depended upon their employment. In Tiberias and in Safed married women and widows sewed clothing, laundered, sold eggs and other foodstuffs. In Jerusalem the Maghrebi women dominated the marketplace with their work, grinding wheat and sifting flour; however, “because of the great poverty and costs, it is not enough even to cover their needs and they are left wanting” (Montefiore Archives, ms 531). Needless to say, in times of drought or agricultural crises these women were left with no means of income.

Conclusion

How then did these North African widows seemingly negotiate space and redefine their position in their respective communities? The relative independence and freedom of widows enabled many of them to carry out their dreams, fulfill their vows, and express their own religious aspirations. These women immigrated to the physical and political backwaters of the Ottoman Empire, often from larger, more developed and thriving urban communities in North Africa, primarily out of their great emotional and spiritual attachment to the Holy Land, emphasizing its centrality in Jewish life. They came to achieve higher levels of personal religiosity and to fulfill their dreams and vows. They visited the holy sites and graves, poured out their personal prayers and supplications and used their physical service to the community’s scholars and its synagogues to achieve their spiritual goals.

Aliyah from North Africa, and specifically the large numbers of women participating in these migrations, not only added to the social weave of the communities but in fact changed it. The very fact of women’s immigration and their presence in the Holy Land asserted their rights to achieve their own self-defined goals, while at the same time reworking tradition to accommodate them as women living and working independently, even if economic necessity dictated dependence on communal funds. These women utilized old strategies and took advantage of new opportunities to support themselves and to find housing and employment in order to fulfill their religious aspirations by continuing to live in the Holy Land, in spite of the difficulties. The same deep love of Zion and desire to achieve elevated levels of personal sanctity which motivated these women to migrate continued to fortify them after their arrival in the Holy Land and gave them strength to cope with the severe poverty and enormous problems of daily life in nineteenth-century Palestine.

Archives, London School of Jewish Studies. Copies in the National Library of Israel, Institute of Microfilmed Hebrew Manuscripts.

Archives of the Ben-Zvi Institute for the Study of Jewish Communities in the East.

Bashan, Eliezer. “The Role of the Jewish Woman in the Economic Life of North African Jewry” (Hebrew). Mi-Kedem u-mi-Yam: Studies in the Jewry of Islamic Countries 1 (1981): 67–84.

Bashan, Eliezer. “On the Attitudes of Moroccan Sages in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth centuries towards the Obligation of Aliyah to Erez Israel” (Hebrew). In Vatikin: mehkarim be-toldot ha-yishuv (Vatikin: Studies on the History of the Yishuv), edited by Haim Z. Hirschberg and Yehoshua Kaniel, 37–41. Ramat Gan: Universitat Bar Ilan, 1975.

Ben-Ami, Issachar. “Folk-Veneration of Saints among the Moroccan Jews.” In Studies in Judaism and Islam, Presented to Shelomo Dov Goitein, edited by Shelomo Morag, Issachar Ben-Ami, and Norman A. Stillman, 282–344. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1981.

Ben-Arieh, Yehoshua. Yerushalayim ha-hadashah be-reshitah: ‘ir birei tekufah (New Jerusalem, the Beginnings: City Reflected in its Times). Jerusalem: Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, 1979.

Ben Ya’akov, Michal. “The Immigration and Settlement of North African Jews in Nineteenth Century Jerusalem” (Hebrew, with English abstract). Ph.D. diss., The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2001.

Ben Ya’akov, Michal. “The Montefiore Census: The First Modern Census of Jews in Erez Israel.” In Papers in Jewish Demography, 1997, edited by Sergio Della Pergola and Judith Even, 79–87. Jerusalem: Association for Jewish Demography and Statistics, 2001.

Ben Ya’akov, Michal. “Aliya from North Africa to Erez Israel in the Nineteenth Century: Myth and Reality” (Hebrew). In Tsiyon ve-Tsiyonut be-kerev Yehude Sefarad veha-Mizrah (Zion and Zionism among Sephardi and Oriental Jews), edited by W. Zeev Harvey, Galit Hasan-Rokem, Haim Saadoun, and Amnon Shiloah, 297–303. Jerusalem: Misgav Yerushalayim, 2002.

Cavallo, Sandra and Lyndan Warner, editors. Widowhood in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. New York: Longman, 1999.

Della Pergola, Sergio. “Aliyah and Other Jewish Migrations: Toward an Integrated Perspective.” In Studies in the Population of Israel in Honor of Roberto Bachi, edited by Uziel O. Schmelz and Gad Nathan, 172–209. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1986.

Deshen, Shlomo. The Mellah Society, Jewish Community Life in Sherifian Morocco. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Deshen, Shlomo. “Women in the Jewish Family in Pre-Colonial Morocco.” Anthropological Quarterly 56:3 (1983): 134–144.

Elbaz, R. M. Laws of Moshe (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1911.

Friedman-Kasaba, Kathie. Memories of Migration, Gender, Ethnicity, and Work in the Lives of Jewish and Italian Women in New York, 1870–1924. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996.

Goldberg, Harvey E. “Family and Community in Sephardic North Africa: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives.” In The Jewish Family: Metaphor and Memory, edited by David Kraemer, 133–151. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Golledge, Reginald G. “A Behavioral View of Mobility and Migration Research.” Professional Geographer 32:1 (1980): 14–21.

Hyman, Paula E. “Culture and Gender: Women in the Immigrant Jewish Community.” In The Legacy of Jewish Migration, edited by David Berger, 157–168. New York: Brooklyn College Press, 1983.

Lamdan, Ruth. A Separate People: Jewish Women in Palestine, Syria and Egypt in the Sixteenth Century. Boston: Brill, 2000.

Lee, Everett S. “A Theory of Migration.” Demography 3:1 (1966): 47–57.

Lim, Lin Lean. “Effects of Women’s Position on their Migration.” In Women’s Position and Demographic Change, edited by Nora Federici, Karen Oppenheim Mason, and Sølvi Sogner, 225–242. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993.

Luncz, Avraham Moshe. Jerusalem: Yearbook, vol. 1. Vienna: Georg Brog, 1882.

Melammed, Renée Levine. “Sephardi Women in Medieval and Early Modern Periods.” In Jewish Women in Historical Perspective, edited by Judith R. Baskin, 115–134. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1991.

Messas, Yosef. A Treasury of Letters (Hebrew). Jerusalem: Y. Abikasis, 1968.

Morokvaśic, Mirjana. “Birds of Passage are also Women …” International Migration Review 18:4 (1984): 886–907.

Sered, Susan. Women as Ritual Experts: The Religious Lives of Elderly Jewish Women in Jerusalem. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Weissler, Chava. Voices of the Matriarchs: Listening to the Prayers of Early Modern Jewish Women. Boston: Beacon Press, 1998.

Sharpe, Pamela. “Survival Strategies and Stories: Poor Widows and Widowers in Early Industrial England.” In Widowhood in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, edited by Sandra Cavallo and Lyndan Warner, 220–239. New York: Longman, 1999.

Shilo, Margalit. “The Heavenly and Earthly Jerusalem: The Religious Experience of Women of the ‘Old Yishuv.’” In Yerushalayim ve-Erets Yisrael: Sefer Aryeh Kindler (Jerusalem and Erez Israel: Book of Aryeh Kindler), edited by Joshua Schwartz, Zohar Amar, and Irit Ziffer, 218–228. Tel Aviv: Universitat Bar Ilan, 2000.

Shilo, Margalit. Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914. Waltham: Brandeis University Press, 2005.

Shitreet, Elisheva. “Avodah ha-ishah ha-Yehudiyah ba-hevrah ha-masorit shel Marakesh” (Work of the Traditional Jewish Women of Marrakesh). In Ma ‘aseh yadeha: ishah ben ‘avodah u-mishpahah (The Work of Her Hands: Women, Work and Family), edited by Tova Cohen, 35–41. Ramat Gan: Universitat Bar Ilan, 2001.

Simon, Rachel. “Mores and Chores as Determinants of the Status of Jewish Women in Libya.” In From Iberia to Diaspora, edited by Yedida K. Stillman and Norman A. Stillman, 114–120. Boston: Brill, 1999.

Stillman, Yedida. “Attitudes toward Women in Traditional Near Eastern Societies.” In Studies in Judaism and Islam, Presented to Shelomo Dov Goitein, edited by Shelomo Morag, Issachar Ben-Ami, and Norman A. Stillman, 345–360. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1981.

Toledano, Henry. “Moroccan Jewry and the Settlement of Erez Israel: a History of the Various Aliyot of Moroccan Jews from the Sixteenth Century to the Beginning of the Twentieth Century” (Hebrew). In Hagut Ivrit be-Artzot ha-Islam (Jewish Thought in Islamic Lands), edited by M. Zohori et al, 228–252. Jerusalem: Hotsaat Berit Ivrit ‘olamit, 1981.

Tucker, Judith. “Problems in the Historiography of Women in the Middle East.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 15 (1983): 321–336.

Weissler Chava. “The Religion of Traditional Ashkenazic Women: Some Methodological Issues.” AJS Review 12:1 (1987): 73–94.

Zohar, Zvi. “The Meaning of Life in the Holy Land in the Writings of Sephardic Rabbis, 1777–1849” (Hebrew). In Erets-Yisrael el be-hagut ha0Yehudit be-et ha-hadashah (The Land of Israel in Modern Jewish Thought), edited by Aviezer Ravitsky, 326–358. Jerusalem: Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, 1998.