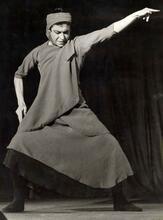

Cilli Wang

Cilli Wang was born in Vienna and was educated in modern dance by Gertrud Bodenwieser, Austria’s major exponent of Expressionism in dance. Wang experimented with movement based on the spoken word and performed various dramas throughout the 1930s, even establishing a cabaret with her husband. However, during the Anschluss in 1938, they were forced to flee to the Netherlands. Here, she developed her personal performance further, inspired by art by Goethe, Disney, Charlie Chaplin, and others. In 1941, the couple went underground. Although her husband died during the war, Wang continued performing, earning worldwide success with her solo performance, Cilli Symphonie. In 1975, she returned to Vienna, where she lived the rest of her life.

Early Life and Career

“I believe art should exist solely for purposes of transformation, the bewitchment of all humankind.” Transformation artist Zäzilie Wang (nicknamed Cilli) began her career by studying dance. Born in Vienna on February 1, 1909, she was the youngest child of Marcus and Regine Wang, who had two other children, Anna and Maximilian. She grew up in an assimilated, liberal-minded merchant family. In 1925 she joined the first, newly-established modern dance class at the Vienna Academy for Music and the Performing Arts, taught by Gertrud Bodenwieser, Austria’s major exponent of Expressionism in dance. From childhood on, Wang—the “Pavlova of Parody”—experimented with movement based on the spoken word.

Wang first appeared on stage at the Komödie theater in 1929 with the reciter Ernst Ceiss. Three years later she presented the monodrama Harlekinade at the Theaterstudio Beispiele (Examples), which she had founded in 1932, together with her husband Hans Schlesinger, a dramatist (author of Harlekinade), poet, director and philosopher whom she married in 1932. In 1931–1932 she was guest artist at Werner Finck’s Berlin cabaret, The Catacomb, and at J. Jushny’s Der Blaue Vogel (The Bluebird). In 1935–1936 she caused a stir at Erika Mann’s Pfeffermühle (Peppermill). She received engagements at Vienna’s cabarets (including Vienna’s legendary Simpl), as well as Stella Kadmon’s Der Liebe Augustin (1935–1936). In 1936 she and Schlesinger established the Fröhliche Landtmann cabaret in Vienna and she joined the Theater der Volkshochschule in Vienna-Ottakring, headed by Schlesinger.

Success in the Netherlands

On tour in Sweden at the time of the Anschluss in 1938, the couple fled to the Netherlands. In 1939–1940 she was hired by Wim Kan and Corry Vonk to appear in their ABC cabaret and at the same time appeared as a guest artist at Cor Ruys’s De Mallemolen. One-woman appearances with dance and speech soon followed at both the Leidschepleintheater and the Centraal Theater in Amsterdam. In 1939–1940 she scored successes at the Palais de Danse in Scheveningen and at the Cabaret Pinguin owned by Alice Dorell and Herbert Perquin. She was a guest artist at Willy Rosen’s Theater der Prominenten in the revue Lache Bajazzo (Laugh, Pagliaccio) in 1940 and the following year in Tot Weerziens, Er und sie, Tempo! Tempo! and Lunapark.

During her exile in The Netherlands Cilli Wang’s transformation art developed to the full. Inspired by Goethe, Disney films, Charlie Chaplin, Wilhelm Busch and Christian Morgenstern, Wang and Schlesinger created a universe of magically ludicrous creatures. Wang “embodied” Max und Moritz, two jolly acrobats (“Max” was balanced on top, with Wang’s head concealed in his—pink, with painted mouth, blue eyes and cheeky straw-hair; her hands were inside “Moritz’s” feet, while her own feet were inside those of “Max”); a Salon Giraffe parodied the refined world of The Hague’s ladies; a bragging soldier swelled and finally burst with his own vanity; a bird ballerina, full of joie de vivre, danced merrily to a tune by Paganini; a fashionable dancing couple (Wang was “he,” who waved his partner over the parquet floor); and World Championship 19..? (full of bitter irony, later adapted to represent Richard Nixon and Leonid Brezhnev who, competing for mastery of the world, are actually “embodied” in one sole person, Wang). She danced a Ländler in a parody of a little Tyrolean peasant woman, presented the Kinder der Flora (Flora’s Children), a Suppenkaspar (a child who won’t eat), and the Fensterputzende Zäzilie (Zäzilie the Window Washer). What was remarkable in all this was the wit, the “punch lines,” on which the transformations were based, composed of movement, Expressionist dance, mime, parody, grotesque, clownery, acting, music, text, costume, acrobatics and lighting effects. No wonder that Cilli Wang rejected the term “Grotesque Dancer” with reference to her work.

Solo Performances

In 1941 Wang and Schlesinger disobeyed the orders of the Joodse Raad (Jewish Council) to report for deportation and went underground. Schlesinger died of exhaustion on April 10, 1945. After the war, Cor Ruys and Martie Verdenius at once engaged Cilli Wang for the Kurhaus Cabaret in Scheveningen. In 1946 she appeared in Wim Kan’s ABC-cabaret and in the cabaret Chiel de Boer. She presented her first textless solo performance in 1946 at the Koninklijke Schouwburg in The Hague, accompanied at the piano by Wim de Vries, who in 1950 became her regular compère and accompanist. On this occasion she first performed her Cilli Symphonie, inspired by Walt Disney’s animated Silly Symphonies, thus launching a worldwide career of solo transformation performance in which she appeared in Israel in 1950, 1956 and 1960–1961. In Austria she appeared inter alia at Vienna’s Großen Konzerthaussaal (1948), at the Wiener Werkel (1951–1952), the Salzburg Festival (1953) and the Wiener Festwochen (1969). Wang, who became a Dutch citizen in 1952, celebrated her twenty-fifth anniversary as a soloist in 1971 at the Koninklijke Schouwburg in The Hague.

Later Life

When Wim de Vries retired that year, Wang decided to end her own stage career. In 1975 she returned to the city of her birth. “No revenge, no reprisal,” Wang said, referring to the fact that the Germans had murdered her parents in Zagreb and that not a single member of her family was still living in Vienna. In 1994 she was awarded Vienna’s Gold Medal of Merit. Living in retirement, without any contact with the city’s Jewish community, Wang nevertheless felt “at home” and “happy,” precisely because she did not personally experience the 1938 Anschluss. She died in Vienna on July 10, 2005.

Alkema, Hanny. De wondere wereld van Cilli Wang. Amsterdam: 1996.

Amort, Andrea. “Cilli Wang: Die Wienerin feierte ihren 90. Geburtstag.” Tanzdrama 1/44–45 (1999): 76.

Idem, und Mimi Wunderer-Gosch, Hrsg. Österreich tanzt: Geschichte und Gegenwart. Wien, Köln, Weimar: 2001.

Bergmeier, Horst J. P. Chronologie der deutschen Kleinkunst in den Niederlanden 1933–1944. Hamburg: 1998.

Van Leeuwen, Ger. “Vastbesloten tot het eeuwige leven: De wereld van Cilli Wang in het Theatermuseum.” Muziek en Dans 9 (1981): 14–15.

Österreichischer Rundfunk. Kapriolen-getanzt von Cilli Wang. Wien: 1961.

Pausch, Oskar, Hrsg. Zauber der Verwandlung: Cilli Wang in ihren Gestalten. Wien: 1981.

Trapp, Frithjof, Werner Mittenzwei, Henning Rischbieter, und Hansjörg Schneider, Hrsg. Handbuch des deutschsprachigen Exiltheaters 1933–1945, Bd. 2, München: 1999.

Würzner, Hans, und Kitty Zijlmans. Oostenrijkse emigrantenliteratuur in Nederland 1934–1940: catalogus van de tentoonstelling. 's-Gravenhage: 1986.

Zaich, Katja B. “Ich bitte dringend um ein Happyend.” Deutsche Bühnenkünstler im niederländischen Exil 1933–1945. Frankfurt/Main: 2001.